Brian Dooley, an Irish human rights activist, and author, has been repeatedly visiting Ukraine since 2014 to report on corruption, LGBT, and other discrimination issues. With the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, his visits have become more frequent, as Dooley wanted “to get a sense of what life is like somewhere other than Kyiv”.

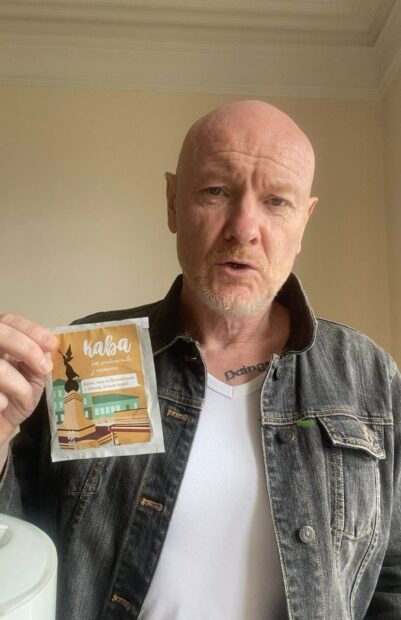

We met Brian after his regular visit to Kharkiv to talk about human rights issues, the Ukrainian Armed Forces, vulnerable groups, the city’s identity, and Brian`s favorite coffee shops in Kharkiv.

Brian about his visits to Kharkiv

“I have worked for the Washington-based NGO called Human Rights First for 12 years. I have been covering human rights issues in Ukraine since 2014, at the end of Maidan [Revolution of Dignity – ed.]. I`ve been going on and off to Kharkiv since 2017, I think. But since February I`ve been visiting every few months. As Kyiv is not the representative of the whole county, right? And neither is Lviv. As I knew Kharkiv a little bit before, it was an obvious place for me to go.

I would say I liked to go there because it is not easy to get to. A lot of people who visit Ukraine understandably go to the same few places, and certainly, everybody who visits Ukraine and is trying to assess what’s happening with the human rights situation should go to Kharkiv. It’s important for me that I do.

When I was there in May it was difficult to do any work, frankly. The city was really at war. It was locked down, there were no vehicles on the streets, and public transport wasn’t working. It was sort of a deserted city, it was difficult to find anywhere to buy food. And I did some stories from there, including about people who were living in the metro. There were very difficult conditions for people.

Then I went again in a couple of months, in August, and there was a huge transformation. The city wasn’t “normal”, and it isn’t “normal” now, but it had really begun to open up. And that struck me. I wrote some pieces – every time I go to Kharkiv I write two or three pieces about it – and I guess the common thread in all of those pieces last year has been the defiance of the city.

I like Kharkiv. It’s difficult to explain, I try to explain it to people often. There is a different feeling in Kharkiv than there is in Kyiv or Lviv. It’s very much an identity-based city. I remember when I did a short piece about one of the coffee shops, “Lia Tiu Sho” [the name reflects the local dialect of Kharkiv citizens – ed.]. They have their merchandise, right? Pretty classy arty staff. But much of it is not so much about Ukraine`s resistance, but it’s Kharkiv’s resistance. And there is absolutely that sense in the city that it`s the people of Kharkiv who are resistant. And I think there’s something commendable about the local spirit. Because clearly you are right up against the border there, and the experience is different just in terms of the rocket attacks which immediately gives a wholly different context of what’s happening in many other parts of Ukraine.

So I`ve been in Kharkiv every few months. I was there in May, October, November, August, and January, and I intend to come again in the next couple of months.”

I see that the city is really opening up, I mean again, it’s not “normal”, but it’s a functioning city with an economy that seems to be working. You can buy food, there aren’t shortages of anything. Of course, there’s a curfew, and of course, the public lighting is out. But you can go to many coffee shops, you have plenty of restaurants to choose from. So when people ask me “What’s it like in Ukraine?” I tend to describe the situation in Kharkiv.

Read the story of Edward, the Canadian who came to help Kharkiv

About the human rights situation in Kharkiv

– Were there any particular human rights issues that drew your attention in Kharkiv?

I have been interested for many years in the situation of LGBT groups in Ukraine. I’ve written a little bit a few times about LGBT organizations in Kharkiv, and how they are responding to the war, and providing humanitarian aid. And I think they are changing some attitudes locally, which used to be hostile – some people, not everybody. And now they see these people are also playing their part in the war – I think that’s an interesting and a positive thing.

And some humanitarian staff too, in terms of seeing how people are making and distributing food. Like I said when I did the stories around people living in the metro, people there were really dependent on food coming, it was impossible to go buy anything if even they had money.

So the humanitarian support, how the LGBT groups are responding, and also most recently about disinformation and Gwara. I think that`s a great and a really important story to see how people are providing crucial service to other local people in terms of telling them what`s true and what’s not, that’s impressive. [During his trip to Kharkiv Brian visited our office to talk to Gwara Media about fact-checking and our PEREVIRKA bot – ed.]

– What issues drew your attention in 2017, when you first came to report from Kharkiv?

At that time I was writing about harassment and anti-corruption activists, people who were exposing corruption. I met several people, activists, groups in Kyiv, and I wanted to get a sense of what else is outside the capital. So I went to Kharkiv, and I met some people threatened for exposing corruption.

When I was in Kharkiv too I met some people whose families were prisoners of war, who had been taken by Russians. So I’ve learned a little bit about those issues too, and how difficult it was for the families to cope with the whole horrible situation when somebody has been taken like that. How difficult it was for them to get information about whether or not their relatives who had been taken were on the prisoners` swap list, where they were, and how to share that information issue. Which I would say is still an issue, and is now an even bigger issue, because there are so many more prisoners, of course.

– What main human rights problems in Kharkiv do you see now?

Well, clearly, the situation is very different from a year ago, as in January 2022. I had been in Ukraine in August of 2021 meeting human rights activists – some from Kharkiv, some from Kyiv, and some from other places. We were working on those sorts of issues around anti-corruption, they were doing advocacy around women’s rights, LGBT rights, the whole range of rights. And clearly, many of those now had to adjust what they were doing to respond to the crisis.

People I knew before who were engaged mostly in advocacy work with the government or internationally have become medics, or providing humanitarian aid. Many of them very quickly and I think very impressively switched to documenting war crimes.

The whole situation clearly was upended, and I think that was pretty impressive about many human rights defenders who had been used to working on one issue, when the war came they managed to respond and completely switch to working on something else.

So I’m guessing Gwara did not do much of this disinformation before February-March last year, and now it has become an expert. And the most important is people trust it and really want to know the truth.

I see that happen a lot, and I think that’s very impressive that people who are used to something and have a comfort zone of working on a particular issue or a particular area now have just had to focus on something else and they are doing that very well with networks. I had networks on how to organize people, clearly IDP [internally displaced persons – ed.] problems, all of that.

The main problem in Kharkiv that I see for human rights activists is very similar to everybody else’s problems. Just staying safe, staying warm, staying alive, staying connected. And trying to do something to protect the vulnerable whether that’s through soup kitchens or reassuring people that the latest rumor isn`t true, whatever it is.

– The problems of vulnerable groups still exist, but now are often overshadowed by this global task of just staying alive.

I don`t for a second believe that the new challenges are or should be addressed instead of the old ones. There are plenty of “old” issues in the new context.

Women’s rights are clearly now an issue in the last year. And many other issues around this, but in terms of women’s experience, in terms of being able to leave the country and all the challenges that pose with it, having to take care of families perhaps on their own in a different country. Or war-related sexual violence. Clearly, it’s not like that began last February, but it’s on a scale now which wasn’t there before.

My organisation is helping to promote a guide, written by local Ukrainian experts, on how the media should report war-related sexual violence.

LGBT issues too – I see the war in a sense has opened some doors, some of the LGBT groups locally in Kharkiv have now changed attitudes towards them. I also think that it’s very possible that the legislation on same-sex partnerships may succeed. And I think that isn’t despite the war, I would say in some sense that’s because of the war, that the public attitudes are changing. For lots of reasons, and I think they were changing before the war, but since the war, people see the contribution made by LGBT people to society, to the effort.

That’s not like those issues have gone away, and absolutely they should not be on hold until the war is over, which is sometimes what happens. But there are just extra huge, immediate urgent things sometimes that people have to take care of. Like eating and drinking.

– What changes in the human rights situation have you noticed since the beginning of the full-scale war in Ukraine?

A lot has changed. Not for all, I’m aware that for many people in Ukraine, things began in 2014, in terms of being occupied and that sort of aggression towards them. The biggest difference that I see is the way human rights activists are adjusting to new challenges.

There is a change I didn`t mention: men can’t leave, women can and some do. Another thing is this international advocacy arm of civil society which I think has been very effective. I know that there are many women, human rights defenders, and activists who can and do very effectively advocate across the main centers of Europe – it`s London, Brussels, Geneva, Paris, Warsaw, and also in the US.

And I think from the international point of view it was interesting to see how welcome they are and how much access they have. People from other conflicts who were trying to get an audience in London or Washington sometimes struggle, whereas Ukrainians as you see – and quite rightly! – Ukrainian activists who are lobbying the governments in the western capitals are often given pretty good access and are heard. That doesn’t mean they always get what they want, but they get the opportunity to advocate. And as far as I see they have used this opportunity very effectively, and the level of advocacy has been great.

– What place does Ukraine now take in the human rights defenders` activities?

There are human rights activists in some countries that are targeted by dictators, and some in democracies too. And that’s usually the places where I work – places like Egypt, the Emirates, or Bahrain. I did a lot of work in Hong Kong in the last couple of years. And I guess the dynamic has been different here. The main danger for the human rights activists in Ukraine is primarily not from their own government. Whereas in most of the places I’ve worked it is from their government. So it is a very different dynamic, the source of dangers that people face where I usually work is their own government officials, they are harassed and threatened, jailed, and tortured. sometimes killed by their government. Clearly, in Ukraine those dangers are there, but not from your own government.

For instance, when I am in Kharkiv, that sense of danger is clearly there for anybody in the city, because you can hear and feel the rockets and the attacks pretty regularly. But I guess – I don’t want to compare that one is easier or harder than the other, that’s not how I think of that, but in other countries, the danger for me is I`ll be followed or arrested or suffer some sort of personal attack by a government who sees me working with local human rights activists, and certainly that’s the danger that local activists are living with every day.

Read the story of Sylvia, an Austrian who bakes bread for the liberated settlements in Kharkiv

About human rights in the army

– What is the situation with human rights in the army?

I think the useful and senseful idea is that the Ukrainian military has a military ombudsman.

I hadn’t heard a much better idea before the last month though I believe it has been kicking around for a while. But I think that would be a very useful move by the government to appoint a military ombudsman.

Clearly, there are going to be challenges for any army when you have a huge number of civilians volunteering in such a crisis so immediately, without training necessarily, or much experience. Being absorbed into an army is gonna be challenging both for the volunteers and the army. Many reports talk about the difficulties of that. People adjusting to chain command, and all of that. A really independent military ombudsman, who people within the military believe in, helping their rights to be fully respected, could have somewhere independent and powerful to go to.

A rights-respecting society is a stronger society, and that just would be better for Ukraine.

– What do you think about the controversial Amnesty International report? [Amnesty accused the Ukrainian armed forces of “launching strikes from within populated residential areas as well as basing themselves in civilian buildings.” – ed.]

I used to work for Amnesty years ago, I stopped in 2010. I wasn`t there when all that was happening, I don’t report on what discussions go on in other human rights organizations. I`ll be responsible for my own reporting, that’s it.

About “the day after”

– We are dealing with great danger coming from the fact of the war. What do you think are the main problems we will face after the victory that we don’t have a chance to process now?

That is a great question. I think that it’s difficult for the people in a war to think for the day beyond the end of the war. But I think that as far as it’s possible to do that`s a useful exercise.

I worked with a human rights organization focused on the war in Syria, talking to activists working in Syria during the war. It was called “The Day After”. It was trying to concentrate people’s minds on what happens the day after the war ends. What are we gonna do? The old problems won’t go away, right?

That mindset of “the day after” is a very useful one, I think. Clearly, for Kharkiv and the rest of Ukraine, the problems it will face the day after the war won`t be the same as the day before the war started. It’s not like we kinda reset and go back to January 2022.

It’s gonna be a huge challenge and difficulty in rebuilding the infrastructure, obviously. But also rebuilding society. I wouldn’t say that all of that is negative, I think there would be some opportunities there for people to perhaps assert their rights in a way they found more difficult a year or two years ago.

The returning number of people who are living outside of Ukraine now. Clearly, logistically I don’t think that’s gonna be horrible or difficult, there could be some positives for that. People who have lived in other countries may have different experiences seeing new things, perhaps learning new skills, but clearly, that’s gonna be a major readjustment when who knows how many people will come back, children will come back after being away at least months.

So I don’t think I have any great insight into that other than to say it’s really not too early to start thinking about how to rebuild. Even if you don’t really know when that phase starts.

In South Africa, when activists were struggling to end the racist apartheid regime, they drafted a new constitution for what South Africa would look like after the end of apartheid – the Day After Apartheid – I guess. And it was very successful, it was the basis of the country’s new constitution, and the process of imagining what a society would look like, should look like, in the future was a really useful one.

If I can make this stupid comparison, I talked to a midwife once. She said that she used to give classes to pregnant women and their partners about what is gonna happen during the birth and after that, how to take the baby home and look after it, washing and feeding and blah blah. And she said she realized that was so pointless talking so much about the point after you`re taking the baby home. Because people were just fixating, they couldn’t get beyond what happens during labor and actually having the baby. Everything else after that seems sort of a whole other world, whole other problems. That’s like a stupid comparison, but I understand it’s difficult for people to see beyond how they’re gonna manage through the war, and get through this stage.

– I don’t think it’s a stupid comparison, it sounds pretty relevant, and that’s how it works. Do you have any ideas for the image of Kharkiv in the future? We have our unique background, long for European integration and to keep our own vibe at the same time. What would it look like after the war?

My first answer would be not to listen to people like me and my advice on this. It’s your future to build.

I`d also say that whether Ukraine`s future is formally part of some European system, part of the EU or not, I think it doesn’t matter as much as the values that it lives. You know, there are many admirable things about Norway and Switzerland, which are not in the EU, so I don’t think being in the EU makes the country ultimately necessarily great, clearly, it doesn’t. Many EU countries have serious human rights issues.

It’s about having – I don`t know why they`re called “western values”, they are not western values, they are human rights values, the Human Rights Declaration is 75 years old this year.

There are those things you are supposed to do, and if all countries, even most countries did those, things would be much better. The problem is the countries signing up for this human rights agreement and aren’t implementing them.

So it’s not like there isn’t a plan for a rights-respecting society. There is, there are many. And I think what’s needed is the political will, the political energy, and the political power to make that happen.

I do think one possible outcome after the war is that there is a real push for Ukrainian society to adopt many of those values. War reorders society in many cases. There`s a chance for Ukraine to solve some of its 2021 problems. So I’m pretty optimistic about it, actually. Are you?

About Kharkiv under attack

“The thing that’s coming to my mind when I`m thinking about Kharkiv is the defiance and people realizing that going about their everyday life is an act of resistance.

If you go for coffee in a city that is under regular, almost constant attack, you are doing something to resist. You are refusing to stay in the basement. It’s an act of defiance, getting up and going out. And I think that’s important.

I tried to give blood when I was in Kharkiv, and I wasn’t allowed. In the system I was trying to give blood, foreigners can’t do that.

People asked me mostly about what Kharkiv was like if it was scary and all of that. There`s a difference in those warnings: in Kyiv, in Lviv, in all the other places I`ve had experiences of, you have a warning and you know you`ve got or you believe you have 10-15 minutes to find a shelter. (Although I saw in Kyiv this week was that there were rocket hits without any warning.) And in Kharkiv, there’s just constant tension.

In August in Kharkiv the neighborhood where I was staying was being attacked. And I was really scared one night. If you spend any time in Kharkiv, you spend a lot of time sleeping on the bathroom floor, and I was sitting in the corner on the bathroom floor. And the explosions were close and I was physically shaken by them. And said my prayers.

Most of the time though the experience is one of a constant general stress, knowing that something may happen.

But either you decide to let that control your life or you try to control your own life and go meet people, and try to live with some degree of normality.

I was really worried at the start of the winter seeing how cold it normally gets in Kharkiv. And of course the infrastructure, that’s what people were telling me in August – the city infrastructure is going to be attacked once the winter comes. You are halfway through the winter now. And of course, there’s been a lot of damage, and of course, there’ve been a lot of casualties. But the city doesn’t look anywhere near broken. There hasn’t been a mass exodus of people. Hundreds of thousands of people leaving home, that just isn’t happening. The damage has been real, but the repair seems to be done daily quickly. I know that the winter has been fairly mild until now, but I’m very optimistic that Kharkiv will get through the winter. Not without any attacks, not without casualties, not without damage. But the city isn’t gonna be frozen to surrender, it just won’t be.

And I’m saying these positive optimistic things just for the sake of it, I really mean that. Kharkiv looks like it’s been coping pretty well with the temperatures and the attacks.”

About problem solutions

– What can Ukrainians and the international community do to protect human rights in the country and resolve the existing problems and issues?

I don’t know any country that has resolved all the human rights issues. On the other hand, it’s not that complicated. There are basic standards that the Ukrainian government and all the other governments, fortunately, signed up to. To respect some rights. The implementation of those is a problem.

I don’t see that a country like Ukraine can’t do that. It’s a matter of political will and, clearly, huge strides were made after 2014. It’s possible, even likely, that at the end of the war, there will be another sort of surge of energy where people want to build a society that is better than the one before 2022.

I`m long-term fairly optimistic that you`ll see how well civil society is performing. And I think that’s important that the public sees how well the activists and civil society and the independent media are doing. Because I think that while work is going on a lot of the time, the public often does not see or appreciate it. And human rights activists aren’t necessarily very good at showing the anti-corruption benefits or any of the other benefits that they are bringing to society. Whereas I think that in a weird way the war mixes up society and reorders it a little bit that civil society will be more appreciated than it was before, and human rights activists will be more appreciated than before.

That isn’t just hopeful talk, I really think that’s true. The difficulty at “the day after” may be making sure that you have a seat at the table and your voice is powerful and listened and you get to reshape post-war Ukraine.

There are examples all over the world of how to do it and how not to do it, right? Women’s voices often get sort of suppressed or shut out of those post-conflict, post-war conversations. It’s important that they don’t.

– So we’ll need more human rights activists to be heard.

You can never have too many human rights activists (laughs).

About technologies

– What technologies are used to help human rights activists? Which of them are used or can be implemented in Ukraine?

When I share my views, I hope that they are not really my views in a conversation like this – I’m trying to reflect the views of human rights activists in Ukraine as I hear them. Some of them say it would be useful to have some more sophisticated drones to map and to really gather evidence around war crimes.

Also, I think that an adjustment to the general Ukrainian bureaucracy could and should be made. Sort of modernize and get beyond the paper-based bureaucracy. The process of trying to prosecute people for war-related crimes – there are so many resources put into it both by the human rights activists, by the civil society, and by the government. But those prosecutions, those inquiries, those investigations are victims of a very old mindset, where the criminal justice system still depends on everything being printed, and on paper.

I know that some of the groups are recording evidence of war crimes. So just one simple thing – sounds simple, anyway – is for the court, the criminal justice system to be able to accept evidence digitally rather than having to be printed out.

I think if that adjustment could be made it would speed up, modernize and make it much more efficient the whole process.

– What do you think about instruments like Clearview [Clearview AI’s facial recognition – the “powerful search engine for faces, letting authorities potentially vet people of interest at checkpoints” – ed.]? Are they potentially harmful, as discussed in the media?

Technology in itself is usually not a problem. It’s who has hands on it, who has control over it – facial recognition, sound recognition, voice recognition. I would say that in some circumstances those things are okay, but the problem is that we`ve seen them being abused so many times that people are now very aware of them, see SST cameras in the cities, and so on. If used properly, they can enhance human rights, but the experience is in too many places they are abused.

I don’t want it to present as a huge positive for Ukraine or Kharkiv, but it is an opportunity that discussions of that sort of thing are now much more alive and much more real than they were two years ago. Now there is pressure on the digitalization of the criminal justice system that wasn’t there a year ago.

And that disinformation staff – look at the advances in tech countering disinformation can have. The trans-scan websites to know in advance if somebody says “I`ve heard that on such and such Telegram channel”, or “such and such a website”, or “such and such a radio station”. The technology there to be able to say “Oh wow, we`ve heard 50 reports from that Telegram channel and they were all propaganda”. That sort of tech is not that sophisticated and not that difficult, but very useful.

– So it`s mainly not about the technology, but who and how uses it, right?

Absolutely. And who gets to regulate it, who gets to complain if they think that technology is being used wrongly against them.

If you have these safeguards in place, then absolutely the technology can be a huge benefit.

About Kharkiv as a city

“Here’s what I think, and I hope no-one’s going to be offended, right?

I think Kharkiv has a very strange ugly charm.

I could easily go to Ukraine and not go to Kharkiv, right? Nobody in my office or anywhere else would say “Why didn’t you go east, to the border city?” But I am drawn there because it is a different type of place, has a different taste, there’s a different sensation there.

My impression is that it’s a city with something to prove. In a sense, the war is showing what Kharkiv is made of, I think. To the world and to other parts of Ukraine, what it’s really about.

When you ask other people what they think of Kharkiv, they often will talk about it being sort of tough, and I think that’s true, though I also think it’s a pretty fashionable place too, and I think it’s not always appreciated.”

– Do you have any favorite places in Kharkiv?

I think that the Thermometer [the giant thermometer on the facade of one of the buildings in the city center, one of the Kharkiv landmarks – ed.] is ridiculous and absurd and ugly, and because of that, I love it. I can’t imagine many other cities in the world that would take pride in that, right? And because Kharkiv does, I love it for it.

Otherwise, it’s not about the particular places, although I believe that you have the first or the only Museum of Gender in Eastern Europe, which is closed right now, so that doesn’t count. The train station is very Kharkiv – functional and pretty efficient but with an artistic beauty to discover too.

There are a couple of coffee shops I always go to. “Lia Tiu Sho” is one, “Rabbit” is another one, and I often meet people, and activists there. I go to other places because of the spirit of it. You know, what was funny, when I looked at Gwara Media last week, I saw that you had also profiled one of my favorite places that I go, a small restaurant called “Vintage Bureau” – I liked that place too.

– So it’s more about the vibe than about the places for you, right?

Yeah, I don`t wanna knock Kharkiv`s architecture, I’m sure it’s great. But that’s not why I go, it’s more for the strange energy. The more I learn about the city the more fascinating it becomes.

I was researching a few months ago and wrote a small piece about the first international war trials, which took place in Kharkiv. You know, everybody thinks that the war crimes trials after World War II in Europe were the big ones and the first ones, but actually Kharkiv had its own trials before that. I think it convicted three nazis and one collaborator. There is amazing footage of the trial and also of them being taken on execution in one of the main squares, that’s an amazing thing. So Kharkiv was ahead of the rest of the world in having an international war crime trial.

Read about Stuart, who came from Australia to see Kharkiv as a tourist

About plans

“I hope to come to Kharkiv again in March or April and plan to visit Saltivka again [one of the Kharkiv districts severely damaged by shelling – ed.]. I came at the start of the winter, in the middle, and want to at the end, but honestly, it looks like the winter hasn’t been as much of a problem as I was afraid it might be.

Also what I tend to do – my organization is based in Washington, and we often – whether it`s in Ukraine or other countries – listen to human rights activists, and what they want from the US government. And I know that Ukrainian activists are advocating for themselves, but I try to amplify that. I`ve been to Washington last week and tried to reflect on what are people saying, and am about to produce a short report on what the US government can do better to help Ukraine’s activists.

That’s some stuff we’ve touched on – the digitalization of the bureaucracy will help with war crime issues, some better supplies in terms of tech and drones, and so on, the US to support the legislation around same-sex partnerships. Some of the other things that I’ve been hearing about civilians in a very difficult position – are civilians who`ve been captured by Russian forces. Clearly, that`s a very difficult situation, and they aren’t really on any prisoner swap lists anymore. In the early months of the latest invasion, it was a mix of civilians and soldiers that the Ukrainian side had presented for prisoner swaps. But it seems like in the last six months or so the Ukrainian authorities have really only asked for soldiers back, and I absolutely understand that, but I think it leaves some civilians in a pretty desperate shape. So that I would be recommending the US also, support the military ombudsman, that sort of thing.

When I`ll be in Kharkiv in March or April I will again be trying to listen to activists, like “what is it that you want, that the US might be able to help with”, and then I`ll go to the US, and see whether I can persuade people to help.

– And in which way do you think the US government can help?

Well, it has a relationship with the Ukrainian government, right? Whenever you think of the level of support or the nature of support that the US is providing, I think the US has a duty, as I think it does in its relations with all other governments it has a relationship with, to urge these governments to depend on human rights. I mean not the US is perfect on human rights at all, it has really serious problems, but I think the US can support some of these things. Not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because it will make Ukraine strong.

And that was also the message before 2022 when I was working on anti-corruption issues, trying to push the US, push the Ukrainian government to do more around corruption issues. Not just because it’s the right thing, but because it makes Ukraine`s society stronger.

About human rights defenders` work

“I`ve been doing this work for a long time. And I’ve realized that solidarity really matters. It’s an easy thing to say, and everybody says “Yeah, we are with you, the solidarity, bit of a fist pump.”

I think it’s important to show up.

I think it’s important for my work not just to stay behind the desk thousands or hundreds of miles away. I think it’s important I come to Kharkiv really to understand in a way that I just couldn’t if I didn’t visit. To hear first-hand from people. I know that it is possible to talk to people online, through the phone, but it’s just not the same. And human rights activists in many parts of the world, including in Kharkiv, say they appreciate people coming in person. And I think to do my work properly, I need to do that.”