The Coordination Humanitarian Center opened in September 2022 after the Kharkiv Oblast liberation. With the Eventroom Foundation’s support, evacuating people who lived near the Pecheneg dam became possible – that is how the center’s story began.

When Kharkiv Oblast was liberated, many foundations immediately went to help big cities, such as Vovchansk, Kupiansk, Izium, and Balakliia. At the same time, other settlements also needed help. That is why the humanitarian center was created in partnership with the Regional Department of Civil Protection and the Kharkiv Regional Military Administration.

Kateryna Lavrenko, a volunteer of the Coordination Humanitarian Center, spoke about the initiative in Kharkiv Oblast, her communication with relatives from Belgorod, a project for people in the liberated territories, and her own vision of Kharkiv’s future.

— Now, I volunteer at the Coordination Humanitarian Center, connecting local or international foundations and residents of the liberated territories needing assistance.

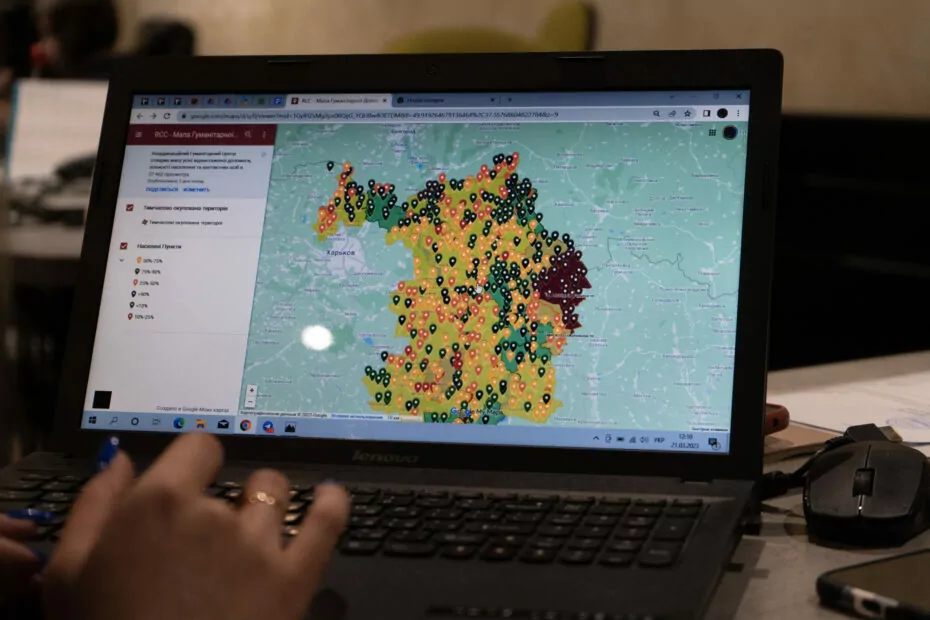

At first, there were seven of us. We collected data on foundation trips, which helped us determine the number of residents in settlements and the contacts of heads. Then we conducted analytics to determine where help was needed and directed funds to areas where there had been no benefactors yet. Thus, we formed a register of charitable foundations, a list of all settlements with the number of residents, contacts of responsible persons, and the level of coverage for products, hygiene, and household chemical products. An interactive map has already been developed based on this register.

Our volunteers daily call communities and districts, updating information on the number of residents, children, older people, and people with disabilities.

— The information about elders and heads of communities is also being updated, as we understand that there were collaborators during the occupation, such people resigned from their positions, and others came. For convenience, we indicate those who know information about their villages.

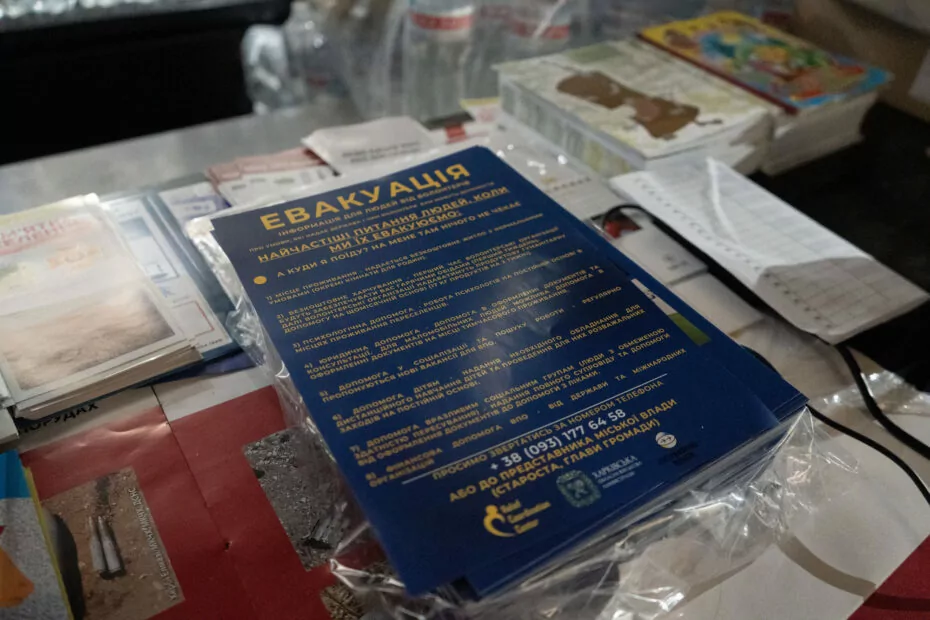

First, the central departments were formed: humanitarian, feedback, evacuation, and internally displaced persons (IDPs). Then the medical department was created to provide addressed assistance with medicines in liberated territories for paramedics, midwives, and hospitals.

Later, our center had the idea to create a new product, a map with 605 settlements of Kharkiv Oblast. One can click on the mark and see the number of residents, the level of hygiene, and food provision. It was created for the charitable sector to see where and what is in abundance and where there is a shortage.

The first war days in Kharkiv

— What did you do in the first months of the war?

I have an interesting story. At first, I was asleep and didn’t hear the explosions, until suddenly my brother from Belgorod [Russian city close to the border from where the aggressor launches rockets at Ukraine – ed.] calls and shouts into the receiver, “Katia, rockets are flying, take measures.”

They live near the border with Kharkiv Oblast and hear the launch of each rocket. My sister Ania texts me and counts how many are in the air and when they will end.

The first days of the war were spent at home. I will say that this is not life but survival. Due to stress, I did not eat and was constantly reading the news. I expected that it would end right now. It seemed impossible that the planes would fly over Kharkiv and bombard the city.

It was terrifying to hear all this, so on March 3, we went to Murafa in the Bohodukhiv district, about an hour’s drive from Kharkiv, and I stayed there for three months. There were 14 of us in one house, but there was enough space for everyone.

Helping the internally displaced persons in the hostel

Before the war, I worked as a manager of two hostels and continued to care for them during the war. They did not close because the administrators who lived in Saltivka [Kharkiv neighborhood, one of the most affected by shelling – ed.] stayed. Some guests did not have the opportunity to flee Kharkiv.

The Ride Hostel did not shut down when the full-scale invasion started because there was a bomb shelter next to it, and we covered all the windows with mattresses. Those who could pay for accommodation did so; those who could not did not. While I was not in Kharkiv, the administrators and I were constantly in touch. The guests received humanitarian aid. We even had Nova Poshta [private Ukrainian postal and courier company – ed.] employees living with us, and they also helped supply cereals and humanitarian aid.

Already in April-May 2022, I returned to Kharkiv and began thinking about how to provide the hostel with money. We need to live somehow, as the owners left Ukraine, although we kept in touch with them. We have prepared a grant project for the accommodation of internally displaced persons in our hostels during the cold period of the year. That’s how we managed to get the Depol Ukraine foundation involved. Their representatives came to us and looked at the rooms` arrangement.

That was my first grant experience. I had an example and filled in a budget application.

Working in a hostel is being 24/7 on the phone, constant staff turnover, and the same neverending problems. Every evening, when I drive home past the hostel, I see that it is working, and people live there according to this project.

Coordination Humanitarian Center

For the first time in five years, I did not work for several weeks, and after massive rocket attacks, I stayed without electricity. I saw that the Eventroom Foundation was looking for volunteers to join the team. And from the first days, I started working there according to the prepared algorithms. All people working in volunteering are responsible and proactive with their vision of life. No one expects anyone to help. On the contrary, they do everything on their own.

— What are your duties at the Coordination Center?

At first, it was correspondence, but then they developed a map with villages, indicating the number of residents, contact persons, and community needs. We call community heads and find out what they need. Next, we look for foundations that can go there and cover these needs.

The most important things are food, household chemicals, hygiene, stoves, blankets, generators, and even water supply restoration.

Also, the seeds. But the idea is more than just giving seeds to the people; we are currently preparing a whole project. We want residents or community heads to have a contract with a business to purchase their harvest. These can be field kitchens for the military or food for IDPs.

— Talking about the harvest, many fields in Kharkiv Oblast are mined. What to do with that? How can the seeds be used?

I expected this question. It is not about large agrarian businesses; now, we are talking about private gardens in the liberated territories. They had their crops last summer.

As for big business, we don’t have a minefield map. As international organizations claim, while there is a war on the territory of Ukraine, they do not have the right to work on demining this or that field.

People in the liberated territories need to socialize, that is, not expect that everyone will help them. In half a year, we have already set up regular assistance. However, of course, some places are difficult to reach. Our volunteers went to Vovchansk and broke three cars, as no roads were there.

We send the charitable foundation; the transport breaks down, and time is spent on repairs. Last year, the action algorithm was as follows: we looked for 15 settlements with urgent needs every week. Then we looked for those who could come there with help.

Today, foundations already write to us themselves. For example, they have 500 sets and ask where to take them. We review the requests and send them to the settlements of Kharkiv Oblast.

— Is humanitarian aid evenly distributed among the Kharkiv Oblast communities? Are Izium, Balakliia, and Kupiansk paid more attention than, say, small villages?

We see the analytics and do everything possible to ensure no imbalance. There are currently no urgent needs or gaps in coverage. Individual representatives of this or that community may say no one comes to them, but we see all the statistics.

We collect information on which settlement shops and markets operate and whether payments or pensions have been made through Ukrposhta [Ukrainian national postal operator – ed.]. It is also important for international organizations to understand whether people have received the funds intended for them.

We also conduct training in psychological assistance, mine safety, and tactical medicine. We help to socialize the residents of the hostels. Together we made trench candles, “kikimora” [camouflage suits – ed.], [camouflage] nets, and socks for the military. Some of the displaced persons find a job in a few months. Although it only sometimes works this way, sometimes there are problems with the fact that everything is brought to them, so people do not have the motivation to work.

Another problem is that people are reluctant to leave the liberated territories. It happens that the application was sent, volunteers arrive, and they are told, “We don’t want to go anywhere; we have chickens, cows, and geese here.”

— Did the war affect communication with relatives and friends?

Now, many people are in Germany, so I miss time communicating with friends who have left. We do not communicate with relatives from Belgorod about the war. We talk about everything with my sister, who lives there. She even showed the situation in Ukraine on her Instagram in the first months, but later she was forced to delete it.

She tried to show the truth, what is actually happening in Ukraine, that they are not hitting military facilities, as Russian propaganda tells. She was immediately dismissed from the civil service. Her husband’s sister reported to his parents that the daughter-in-law was doing something wrong and could be held responsible for it.

Last year, my grandmother wrote on WhatsApp, “Crimea is ours, Kyiv is ours, Kharkiv is ours, there will be flags of the Russian Federation everywhere.” No one asked how I was doing or felt, just messages about Crimea and other propaganda.

It has become easier for me that I can not communicate with my relatives in Russia at all. It is the last straw.

I will never go there under the current government. I want a reinforced concrete wall – let them first put everything in order.

When the 2014 war started, everyone was dealing with their problems; it was not felt in Kharkiv; we lived well here. I think many people now feel guilty for not reacting to the war in Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts.

— The war has been going on for over a year. Do you feel exhausted?

Volunteering is hard work. However, I would feel emotionally bad if I just stayed at home. When you work every day, communicate with people, help them, and solve problems, it gives strength. You see that people are trying to work and evolve even during the war.

Volunteering is hard work.

— How do you see the future of Kharkiv? After all, the city is close to the border with the Russian Federation, and there is always a risk of shelling.

Everything will be fine with us. Kharkiv residents are systematic people who live under any conditions. When there was no light, the generators and starlinks were turned on. We worked even when there was no communication and no light.

Read more:

- Chaotic Shelling, Volunteer Help, and New Routes to Kharkiv. Life in Liberated Tsyrkuny in Ukraine

- “To Break Even is a Decent Result.” How Pouhque Bakery Evolves in Wartime Kharkiv

- How Kharkiv Residents Make City Safer: Relive Project Reconstructs Basements

- From Restaurateurs to Professional Volunteers: 24.02 Headquarters in Kharkiv

by Denys Glushko,

translated by Tetiana Fram

We appreciate you being here. Thanks to you, we can focus on our work, continue in-field reporting and contribute to defending democracy in Ukraine. Please become our patron to develop Gwara Media together.

Follow us on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn for more news, stories, and field reports by Kharkiv journalists.