Exploring the liberated settlements of Kharkiv Oblast, we have already reported from Izium, Hrakove, Balakliia, Kozacha Lopan, and Vovchansk. After visiting these territories, we decided to go even further and see the de-occupied Dovhenke, the last village of Kharkiv Oblast, beyond which Donetsk Oblast begins.

5 months of the battles

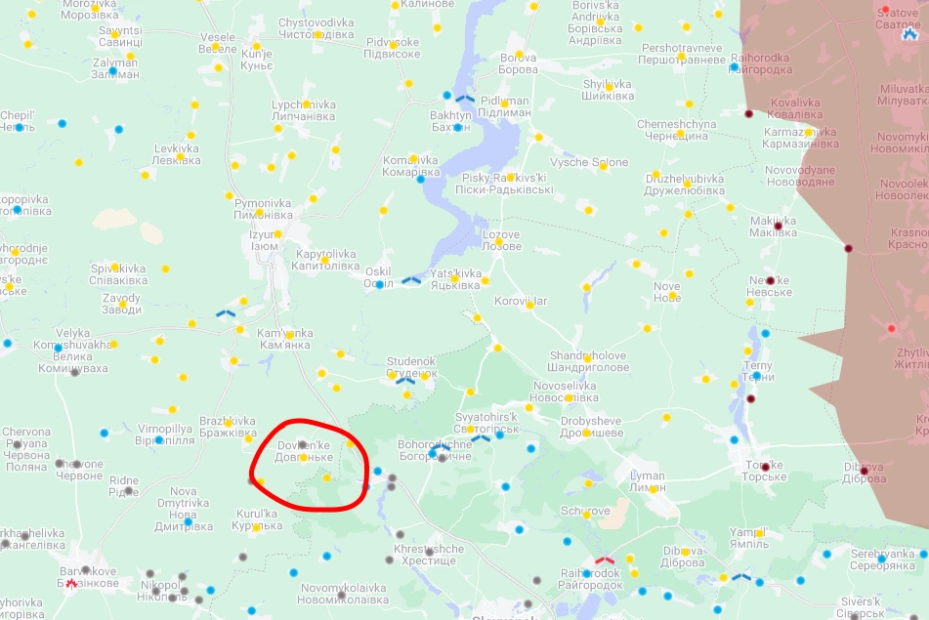

As of today, approximately 60 km separate the village of Dovhenke from the territory temporarily occupied by Russia. About 50 km from this place, across the Lyman, it gets really “hot”: there are ongoing hostilities, the progress of which can be viewed online on Google maps.

Dovhenke is a village of no particular strategic importance, the last settlement on the border of Kharkiv and Donetsk oblasts. However, it is located near the major highway E40, and the Russian army actively tried to take control of it in July.

The Russian troops entered the empty Dovhenke in mid-April. As the locals told us, almost all the residents had left the village in March, with the first sounds of Russian aircraft.

According to Ukrainian Wikipedia, 850 people lived in the village before the full-scale invasion. The resident Lyuda, who herself has fled to Dovhenke from the war in the East, claims that in recent years about 450 residents have lived here.

According to Lyuda, only two old men can be eyewitnesses of the Russian occupation. One of them died, and the other was “taken to Izium by the Buryats (one of the Russian ethnic minorities – ed.)“, so the future fate of the man is unknown.

The village of Dovhenke is the most damaged settlement in Kharkiv Oblast. Due to its remoteness from Kharkiv, on the one hand, and from the current frontline, on the other, the mass media outlets write almost nothing about it.

Meanwhile, if you have come across Maxar’s real-life images on the Internet, illustrating the “heaviest battles in the Kharkiv, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts”, you may remember the legendary photo of a Ukrainian field with hundreds of shell holes. This photo was taken in Dovhenke.

“A handout satellite image made available by Maxar Technologies shows a 40-meter diameter bomb crater and recent shelling with destroyed buildings in Dovhenke, Ukraine, June 6, 2022. Maxar collected new satellite imagery that claims to show nearly continuous and relentless bombardment and artillery shelling of villages and cities in eastern Ukraine as Russian forces attempt to gain control of the Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts,” the message reads.

The invisible people

The de-occupied Kharkiv Oblast is full of broken destinies and disturbing landscapes. According to Izium Mayor Volodymyr Matsokin, 80% of the houses were destroyed in the settlement, and in Kamyanka not a single one has survived. These pictures are truly heart-wrenching, but even this scale of destruction pales in comparison to what we saw in the village of Dovhenke.

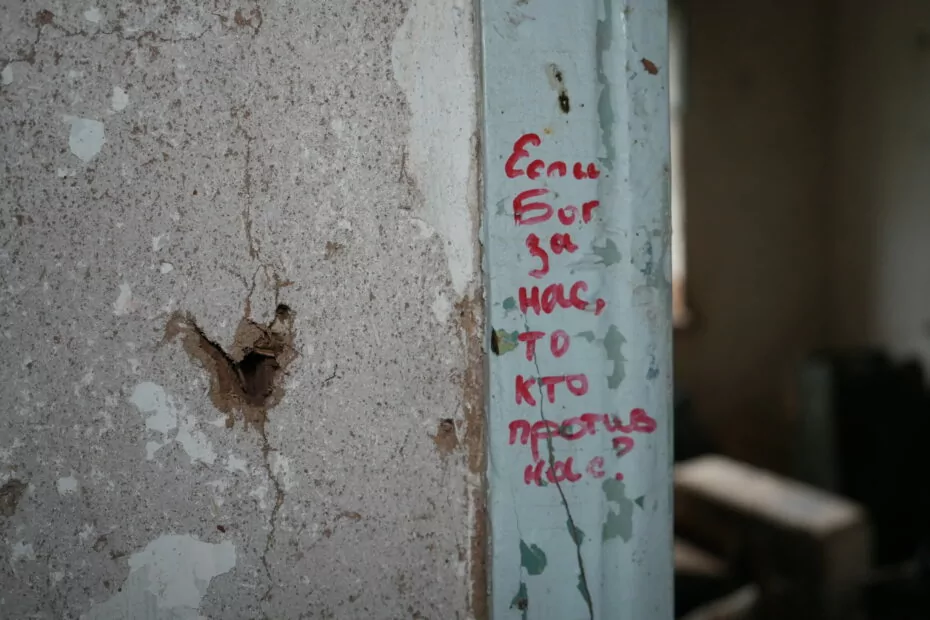

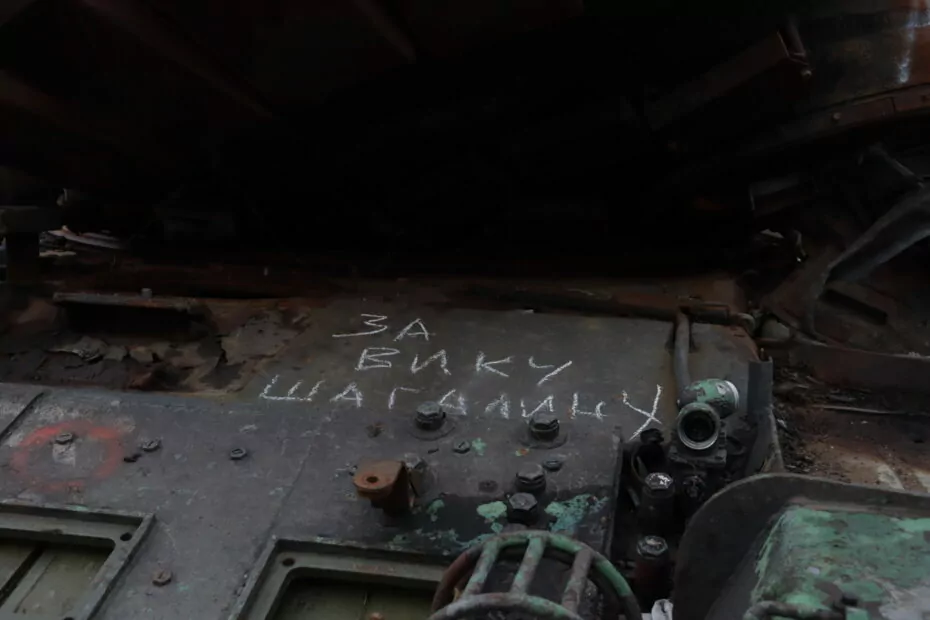

Right on the road leading to the village, after the last roadblock on the way out of Izium, there is burnt Russian equipment left. Here, on the border of Kharkiv Oblast, it has not yet been removed after the de-occupation on Sept. 11.

The mined fields with the warning signs are “decorated” with remnants of combat shells, dead, torn in half domestic animals, and charred tanks.

“For Saltovka!” is written on one of them in large letters. On others, there are more personal messages for the Russian army, such as “For Vika Shagalina!”

It would be an underestimation to say, there is not a single surviving house left in the village. There are no premises with four walls left. Only garbage remained from dozens of private yards, schools and kindergartens, a cultural center, and a water tower.

Obviously, in such conditions, no one lives here anymore.

We had been walking in this horrifying cemetery for about two hours, filming the remains of the military shells in the yards, until we met the first living people. The former residents of the village came to Dovhenke to get their personal belongings from under the rubble. For the man, it was the twisted number plate of his favorite car, and for the woman the childhood photo of her daughter.

It was they who led us to one of the courtyards on the nearby street. There we were lucky enough to meet a few more former residents: Lyuda, Tamila, and their husbands. They have covered the hole in the wall with sacks and boards, put in a new window, and temporarily stay overnight in the house, protecting the remains of their belongings from the neighbors or unscrupulous Ukrainian soldiers.

“We want to be seen,” Lyuda shouts to us almost from the threshold when she learns that we are representatives of the mass media. “We want people to know that we exist. Just look around! How can we live with this?! Who will help us? It feels like we’re invisible,” the woman complains.

The neighbors, who had gathered around the only house suitable for a temporary stay, told us a brief history of the occupation of the village.

In the very first days of the full-scale invasion, the head of the village council, Vitaly Karamushko, fled from Dovhenke — the village was simply left without its governor. In the Viber chat, the old man is condemned and called a traitor, but Lyuda confesses she does not know what she would have done in his place.

“They said that on March 17, from one to three thousand Ukrainian soldiers came here for defense, at first they occupied the empty houses,” Lyuda shares her memories and assumptions. She left the village on March 18, and her neighbors – on March 25. The woman has returned to look at her native house only recently.

Lyuda says that she knew and had no doubt that it would be exactly as it is here. From the mass media reports and the Viber chat, the residents understood that nothing had remained of their village. But when she saw the house with her own eyes, she still cried out in grief.

“Have you noticed the way I’m talking now?” Lyuda says. “I broke my voice from screaming when I came here for the first time [since the evacuation in March — ed.].”

Lyuda`s husband also cried, sitting on the ruins of his house. He had a heart attack not a long time ago. It is unlikely that they will ever be recognized as victims of Russian aggression – although now the family has to find the money for the constant treatment of the man for all his life.

This war is not the first one for Lyuda. The 43-year-old woman used to work as a storekeeper at a wholesale base in Horlivka until Russia invaded Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in 2014. Then “with a bag of money and by her own car” she fled the war to Dovhenke. “It’s ironic,” says Lyuda, “for 8 years we have been afraid to make repairs, I kept saying ” the war is too close.” And right on the eve of February, the family has finally made it, choosing all the best.

Lyuda shows a coat hanger, strong and of good quality, sticking out right between the destroyed walls, in a pile of garbage, where food, jackets of Russian soldiers, Russian military meal kits, and fragments of the new dishes are mixed. The woman cries as she shows the camera the remains of the ceramic pots she used to collect and hang on the fence.

Lyuda filmed her house and posted it on Tik Tok — the video of the destroyed building has got 4 million views. The ceramic pots helped the soldier from Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast who had been forced to use the house to recognize it on the video. Later, he wrote to Lyuda and personally thanked her as the house had saved his life.

Tamila, the woman in whose house Lyuda is staying, has her own tragic story. On the eve of the full-scale invasion, the family fully renovated the neighboring house for their daughter, investing all their savings – about UAH 300,000 (~$8,000).

We walk with our cameras around what should have been the home for a young family, looking at pieces of brand new tiles, wallpaper, doors, modern batteries, and toys that only highlight the complete devastation, the contrast between the comfort and apocalypse, between the living and the dead. It makes us shudder, and Tamila cries helplessly.

The animals who wander through the mines

One of the problems of the destroyed villages and farms in Kharkiv Oblast is lost pets and domestic animals. Besides her house, Tamila also shows us her cow shed. The cattle disappeared from there during the fighting.

Some cows, pigs, and geese were eaten by the same domestic animals due to hunger. Others were killed and eaten by the soldiers who stayed in the houses.

In the yard of Tamila’s house, where we see the remains of children’s toys and broken tiles lie the bones of something large, hopefully just a cow. One cow, the woman says, was blown up by a landmine in the yard nearly two weeks ago. And another one – nobody knows who it belongs to – wandered into their house with an injured and broken hoof (“Probably stepped on a “petal”). Tamila has no money to treat the animal, so she shows us the wound and bandages it with a rag, smearing the hoof with Vishnevsky’s ointment.

Before the full-scale war, there were two large enterprises near the village, “Caravan” and “Zlagoda” (“Harmony”), which created jobs for the locals. Yet according to Tamila, most people lived off what they cultivated and grew themselves.

“We`ve had everything,” Lyuda recalls, “literally every evening we chose what to eat: pork, chicken, or duck meat.”

Today, these animals, which used to live in almost every household, wander through the mined fields, die of wounds, lie on roadsides or become food for starving dogs or cats.

Destroyed crops and ecological disasters are other sides of the Russian aggression, which devastate village after village in Ukraine.

The unburied bodies

However, the dead animals are not all that can be found in almost the front-line villages of Kharkiv and Donetsk oblasts.

The first people we met told us about the body of a dead man, whom no one can bury. He has been lying in one of the nearby houses for several months, approximately from the end of April.

According to Lyuda, the police who came to the village refused to deal with the deceased, advising the locals to either bury him themselves, contact his relatives, or go to the regional center to write a statement.

Many people are not even surprised by that. After all, just 20 kilometers from here, near Izium, at least three mass graves of civilians were found after the liberation. Hundreds of criminal cases must be processed by the Ukrainian authorities in the shortest possible time, so isolated cases are not a priority.

The man lying in Dovhenke is 50-year-old Borys Bolog, who used to work as a handyman at a local enterprise.

“Did he die from Russian shelling?”, we ask. “No,” says Lyuda. “He was not injured, but he lost his mind because of the war.”

The last person to see Borys was a neighbor who came to share food on Apr. 27.

According to the locals, in the already bombed-out house without a roof, completely naked, Borys refused to eat. He kept sitting there and repeating “Hunger and war, war and hunger.” The man died not of the shelling, but of grief, in the remains of what used to be his bedroom.

Today, the man’s body, which no one wants to take away, still lies at the address Vershyna street, 37. The corpse has already decomposed to the bones – the locals took us to look at it.

On the way back, we take a video of the address plaque that Lyuda puts on the brick of the destroyed house, and we hope that we will soon be able to turn this case over to the police.

But it will take much longer for us to recover from what we have heard and seen here.

What’s next?

“You get used to this picture,” Lyuda suddenly says to the camera. – But how to live on? Is it possible to rebuild at least anything? When? And just tell me how to put up with it?!”

We understand what the woman is talking about, as we are not sure it will be possible to forget everything we’ve seen in Dovhenke.

News about the settlements` recovery sounds good in the newspaper columns. But in reality, for the residents of the regions, the process takes much longer and is much more painful, and more difficult.

Humanitarian aid was delivered to Dovhenke for the last time about two months ago – immediately after the settlement`s liberation. Since then, volunteers have not visited it, and the local government does not exist. Not to mention water, gas, or electricity – the infrastructure for supplying these resources is simply ruined. To submit documents for the restoration of their houses or at least to arrange the burial for their neighbor, the locals have to go to the regional prosecutor’s office to get a police order. But where to get money to buy petrol or how to reach the city without any public transport, remains a question.

Lyuda thinks that of the around 450 residents more than half will never return to Dovhenke. Most likely the settlement will turn into a so-called “hamlet”, a farmstead, a tiny village instead of a big one. Maybe one day it will be possible to restore a street or two, but Dovhenke as such will simply not exist. Those few residents who don’t want to lose in vain their privatized land will rebuild their houses at a certain distance from each other. Others will build a life in a new place.

The lack of volunteer organizations traveling to remote corners of the regions is the main problem of the oblast now.

Communities like Dovhenke are often overlooked by big cities and the international community, and their residents are beyond the reach of any coordinated, targeted help.

Lyuda, Tamila, and their neighbors still don`t know how they will spend winter. They say, on the one hand, they should stay here to try to take out their property, at least as scrap metal, and get the minimum funds for living in a new place. On the other hand, it is simply impossible to live here in winter.

“If you ask me, I don’t want to go anywhere,” says Tamila in despair. Despite everything, she spends the night in her house – a building with a door that had been shot and not a single wall remained intact.

It seems that Dovhenke locals would like more than anything just to return to their home, to their jugs and painted children’s rooms, “the very hanger”, the landscape with trees on the horizon.

Today, there are dozens, if not hundreds, of such villages in Ukraine. It is important to realize this to imagine the scale of the Russian crimes and the scale of the tasks that will be faced by liberated Ukraine.

Thousands of people from the de-occupied territories will never return to their former lives. But also thousands, thanks to the Ukrainian Armed Forces, will finally be able to return home.

Olena Myhasko and Serhii Prokopenko, Gwara Media

Translated by Tetiana Fram