Borova is located on the left bank of the Oskil reservoir. Borova river flows into Oskil, and a small pine forest massif separates the settlement from the reservoir. One needs to cross a bridge to get there – which turns out to be important for our story.

The start of the trip

Sunday, 8 a.m. Google maps show that our destination is only a 40-50 minutes drive from Kharkiv. Well, it used to be before the war. We supposed that now the journey would take more time, as in the case with Vovchansk, but we did not expect it to be more than four hours.

First, we navigate by the map and ask the locals. It turns out that the occupiers have blown up the bridges over the Borova river, but no one knows the fate of the particular crossing, so we decide to check it out.

The bridge has been destroyed for a long time. Nearby, we notice a broken car, the wheels of which have already been unscrewed, while the apples are still lying somewhere inside. In front of it, we see a “Ukraine” bicycle and a scooter. First, we suppose it has been abandoned, but later we meet the owner. He shows us the detour route to Borova.

The scale of destruction is impressive. The crossing has been blown up on both sides. Trying to plan a detour using the map, we meet an elderly man. He turns out to be a fisherman and his colleagues are sitting on the bank of the river.

We talk, and the man tells us about the occupation. He is not from Borova, but his village is nearby and they were also blocked without the opportunity to leave the place. He says it was quiet in their village, but they had loads of Russian propaganda. No one expected the Ukrainian military to liberate them so quickly, adds the man.

We wish him good fishing and continue our way. The connection has not yet been restored in this part of Kharkiv Oblast, so our only hope is for offline maps and the residents. Asking several of them we finally discover our further route.

The experience is novel, as we have never been to Borova. All our way the road is terrible, but the scenery is incredible: the sown and well-kept fields, and plenty of sunflowers.

But the further we drive, the greyer everything becomes. Black withered sunflowers turn away from the road, already fueling a bad mood. We see more and more black fields, destroyed houses, and the remains of machinery.

And then we see the first village, although it can hardly be called a village – rather the remains of one. I don’t remember seeing at least one house undamaged. In most cases, the foundation is the only part left of the building. Some of the gates that have remained still have the inscriptions “People” and “Children”. The fact that it has not helped to save the houses feels scary.

We proceed forward, thinking aloud: “Imagine, these are thousands of abandoned lives. And these people are lucky if they have survived.”

All this time, we keep trying to imagine what life was like here before. How the people used to go to work, children used to hurry to schools and kindergartens, how life used to rage here. And now the kindergarten is destroyed, except for the remaining swing, although we are not sure it is safe.

Meanwhile, the road is becoming harder, and the visibility turns poor due to the dust. People, the military, and even more wrecked equipment start appearing on the streets. The machinery is being inspected.

And so we end up in the Lyman district of Donetsk Oblast. It turns out that to get to the village we have to go around the entire reservoir, so we cross the border of the Donetsk Oblast.

It’s 3 p.m. when we finally arrive in Borova. The outskirts are empty, the flag of Ukraine is already painted on top of the Russian tricolor on every pillar.

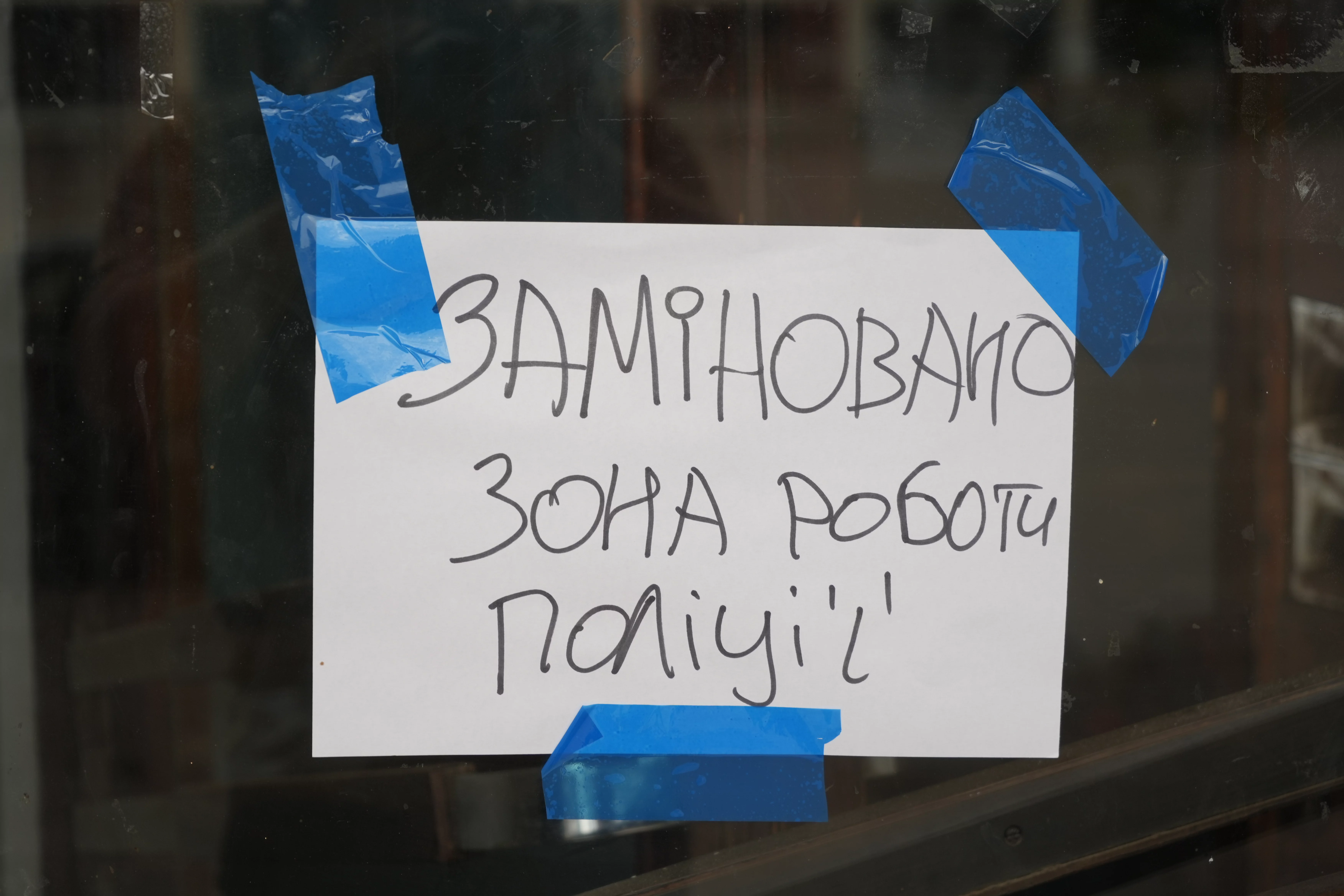

The factories are destroyed, and the premises are mined.

The stalls are painted with curfew warnings written on them.

We proceed to the center of the settlement and get to the school. The windows are broken, all the flowers are gathered in a corner, and beds are scattered – the occupiers have probably slept there.

Nearby, there is an abandoned room with remnants of Russian food packaging – they’ve left loads of garbage.

Opposite is the destroyed postal office with the inscription on the gate in Russian: “No entry”. We can’t pass by the open gate. So we step inside.

The first thing we see is the Russian propaganda newspapers scattered all over the place. “Kharkov Z” or “Russia ru” write that “Russia has come to Kharkiv forever” – sounds scary, doesn’t it?

And people did believe that Ukraine did not need them, that the Armed Forces would not liberate the region, and if they did, the locals would be tortured.

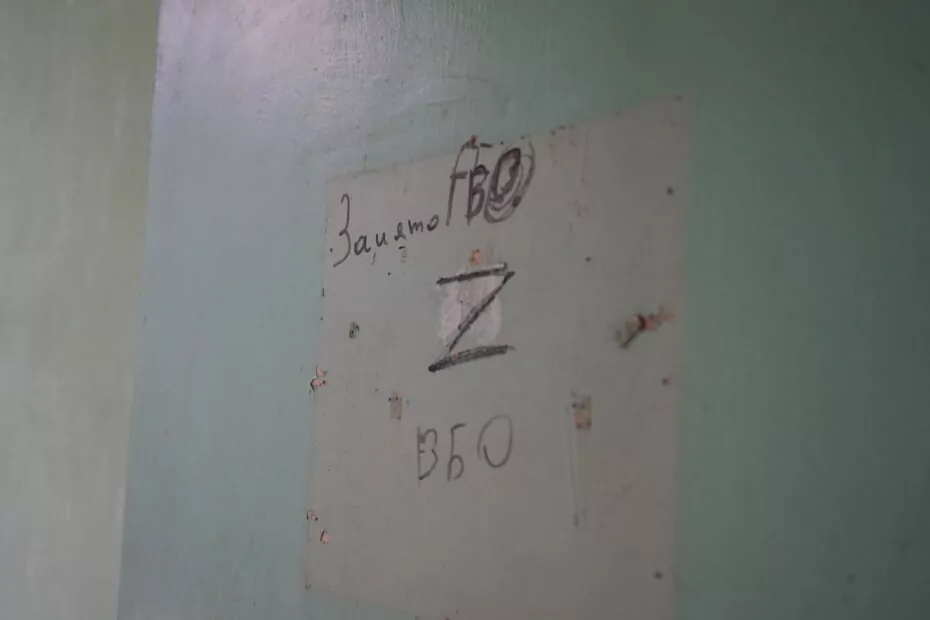

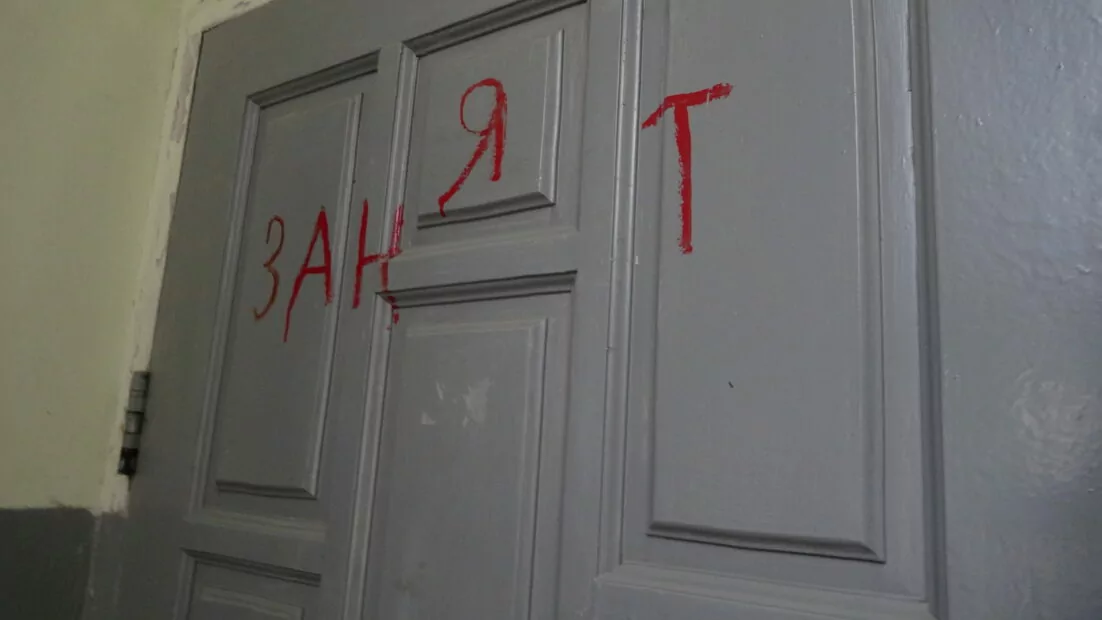

Inside the premises of the post office there is a lot of garbage, broken furniture, and inscriptions “Occupied” or painted “Z” on the doors.

Our next stop is the police station. We are going to find out the details about the liberation of the settlement. On the way we meet people and get surprised when the locals greet us, smiling and calm.

Then we see: a woman comes out of the yard. Another woman is standing across the street, and when the ladies spot each other, they exclaim joyfully and run to hug. And you know, it isn’t just a greeting, it is a long and strong hug, the one when people haven’t seen each other for a long time, a warm and friendly one. We have to slow down because the women are standing in the middle of the road. We drive further and see that the residents are already patching their roofs, and restoring their houses, the streets and lawns are already clean.

Finally, we arrive at the police station. The law enforcement officers meet us there. They say there are currently 18,500 people living in their area, and the city is still being wiped out, so it is early to return home now – but of course, it doesn’t stop the locals from returning.

The policeman tells us how the occupiers intimidated the residents, that the Ukrainian government would not return to Kharkiv Oblast, and that if their village was de-occupied, they would all be killed as collaborators. There was no connection in their district except for one place where the Russians were based. So the residents who wanted to call their relatives had to go to the invaders, where they were allowed to talk on the phone only on speakerphone. Therefore, they did not have the opportunity to get any Ukrainian news at all.

The locals have been so intimidated that they are still a bit afraid of the police. But the law enforcement officers are doing their best to help with the humanitarian aid, and as the police station has access to connection anyone can come there to contact their loved ones. While we are talking to the police, many people come to get in touch with their relatives.

We managed to talk to some of the locals. A family with two children tells us how the Russians tried to force the kids to go to a Russian school. At the same time, Ukrainian teachers lead the classes online, so the parents were preparing their children for online schooling. People say that invaders could grab someone just on the street. They took crops from the local gardens and occupied the people’s houses.

And despite the difficult times, now local people are standing in front of us smiling and waiting for the victory. They are getting used to the new reality and rebuilding their homes.

On the morning of April 14, 2022, the Russian invaders entered the villages near Borova. In the evening of the same day, Oleh Sineyhubov, the Head of the Kharkiv Regional Military Administration, reported that Russian troops had entered Borova and the settlement had been blocked.

The same month Russians shot the evacuation buses with civilians. Seven people died and another 27 were injured. According to the locals, when the drivers saw the Russian military, they stopped the transport and got out with their hands raised, but they were shot anyway.

On Oct. 3, the village of Borova in Izium district was liberated. While the cleanup was still ongoing, the Gwara Media team managed to visit Borova and report from there.

Text by Dasha Lobanok

Translated by Tetiana Fram