“What do they distribute? Hot meals? Is it for everyone? Are you sure?” “Yep, yep, don’t worry,” says one of the women in the queue. She comes to FuMi cafe frequently and recognizes other regulars in the long line.

“Today it’s not that long,” she eagerly shares when we join the crowd waiting near the kiosk at Heroiv Pratsi station in Saltivka district. “On Tuesdays, when they distribute hygienical products, 70-80 people queue here.”

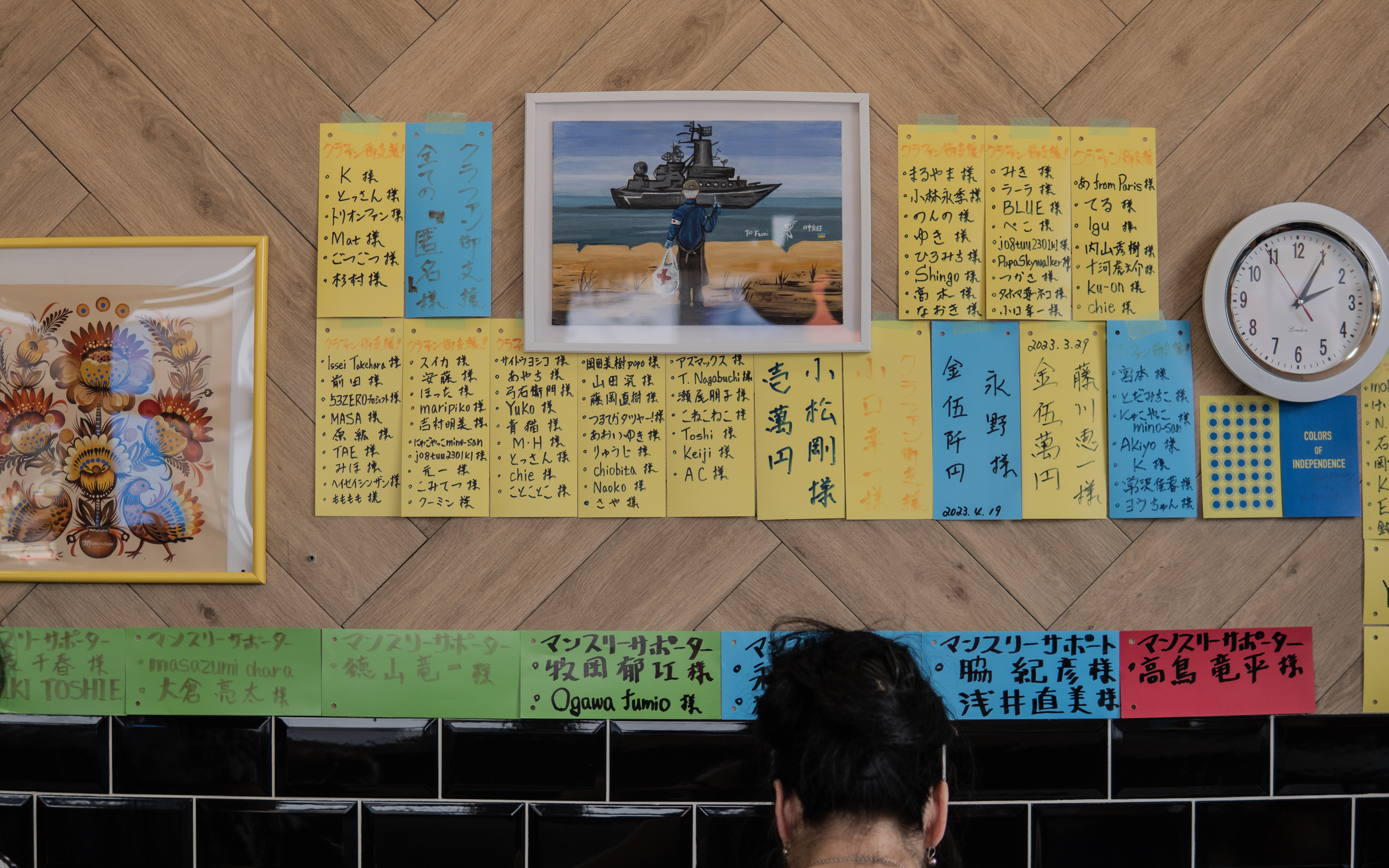

Daily, 75-year-old Japanese Fuminori Tsuchiko and local volunteer Nataliia hand out 800-1000 meals to Kharkiv residents. They do not have weekends. “We will have a rest later,” smiles Nataliia, and we all understand she means “after the victory.”

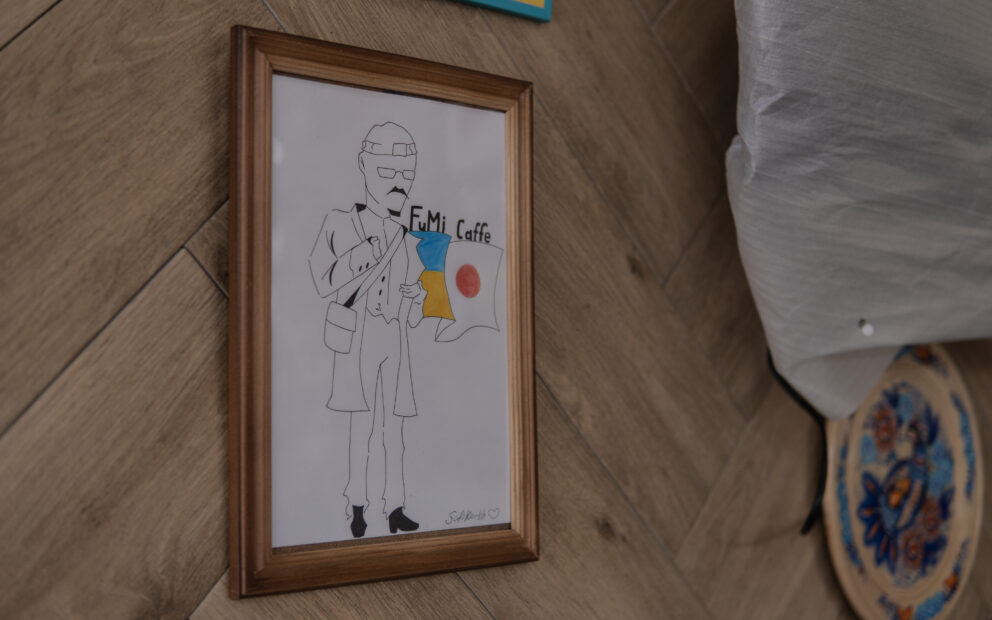

After opening FuMi cafe with free meals for everyone who needs it, Tsuchiko has become a local superstar. However, we encountered his story first in September, when Sasha, a Ukrainian volunteer in Tokyo, visited her native Kharkiv and came to see Fuminori. At that time, Tsuchiko was staying with Ukrainians who lived in a metro station hiding from heavy bombardments. Sasha’s volunteer community in Japan was donating funds for Fumi.

“I came downstairs to the metro station and saw a senior Japanese man. He made an excursion in the shelter for me, and then I talked to the local women. They told me how the man swept the floor in the metro and the nearby market every day and bought food and stuff for the children. He has even gifted them iPads for the first day of the school year,” Sasha recollects.

The cafe

In a metro in Saltivka district, one of the most affected by shelling in Kharkiv, Tsuchiko met Nataliia Hrama, the volunteer. While distributing supplies to the people hiding from bombardment, they got to know the residents’ stories. The Japanese encountered many people having lost their houses and jobs, so after leaving the shelter for a rented apartment in the same neighborhood, Tsuchiko launched regular humanitarian aid distribution near the metro station for everyone who needed it. A free cafe became a logical development of this initiative.

“We planned to hand out just the simplest things, like warm soup and tea, for the people who used to live in the metro,” shares Nataliia. Today FuMi’s menu is much more extensive and includes everything people donate to the charity cafe. “Sometimes people bring just a jar of jam or pickles, as they want to help but don’t have money to donate. And this jar is precious, and it helps us. There is not such a thing as too little help. We are over the moon to have every chunk of bread. Everything counts,” says Nataliia.

“What is the biggest problem or need for your cafe now?” I ask Fuminori and Nataliia as we sit on the low stools behind FuMi cafe at the market.

“It’s always money,” simply says Fuminori. He and Nataliia plan to open another charity cafe near another Saltivka metro station and develop the FuMi free cafe chain to feed even more people. This ambition requires more resources.

“Fuminori has spent all his savings on helping people,” explains Nataliia. “Now I have registered a fund for donations, and we buy the supplies from the contributions we get from Japan, other countries, and also from locals. I used to work in the restaurant business before, so when FuMi Cafe expanded, I knew who to invite to join us. We pay salaries to all the cafe employees. We got support from the regional government, who provided us with some kitchen equipment. Also, the market administration helped us by providing the premises – we started with a tiny kiosk which has already become three times larger.”

“The biggest challenge for me is to prevent Fuminori from handing out all the sweets and cookies at once,” smiles Nataliia. She says Tsuchiko can not let go of any child visiting the cafe without a sweet treat. The woman tries to reason with him to do it not daily, “Maybe once a week, or maybe not a kilo of sweets for a child!” But as of now, her attempts are futile.

Fuminori

We are lucky enough to see Fuminori when he hosts Koichi Kuwabara, a free hugger from Japan. “He is my friend, not my son,” smiles Tsuchiko, introducing Kuwabara to us. Fuminori invited Koichi to help with his project with social media development – Fumi admits he is not an expert in “these technical things” but needs to attract attention and support to his initiative.

Koichi speaks fluent English and helps us to get to know not only Fumi’s project but him as a person. That is how we find out that Fuminori is keen on fishing but does not have the time or proper equipment to do this in Kharkiv. “You are a fisherman, wow, Fumi! Even I didn’t know it,” laughs Nataliia.

Tsuchiko also misses the cinema, as he loves watching films. All the movies were closed in Kharkiv for a long time, but Fuminori’s face lightens up when we say they have resumed work now, “Maybe I will check it out, if they have English subtitles, of course.”

Among his favorite things about Kharkiv, Fumi names the blue sky, the air conditioners, and autumn. “It is so beautiful. The leaves, the colors,” Tsuchiko makes abstract movements with his hands to show the golden leaves scattered everywhere around his cafe.

What was the most challenging moment for you in Kharkiv, Fumi? I ask one of my traditional questions.

“When I stayed with people in the metro hiding from the bombardment, trying to help them. Because I didn’t know how to do that, how to help.”

And what was the happiest one?

“When I stayed with people in the metro hiding from the bombardment, trying to help them.

It was both the hardest and the happiest time in Kharkiv for me.”

Why did you choose Kharkiv, by the way?

“Because I knew the situation there was the most complicated, and people needed help there.”

When asked about his daughters in Japan, Fumonori’s eye expression changes. It seems the subject is sensitive for him.

“We stay in touch,” says Fuminori. “But they are grown-up, independent women now. Life in Japan is tough. One needs to work hard to succeed. So they are doing their thing, and I am doing mine. And I am happy it is like that, as I am free to do whatever I want,” he smiles.

I know you think Japanese people and Ukrainians are pretty alike. In which way?

“You work a lot, often without days off. What surprised me the most was that Ukrainians don’t take a lunch break at work. Even in Japan, we have an hour’s break when we relax. But here, you take just 10-15 minutes to eat and rush back to business.”

“It’s delicious.” “Have you ever seen the Japanese himself here? – Sure, he is always there. He even cleans the premises and washes the dishes.” “The first course, the second course… And hygienic products every other Tuesday.” “You can eat in or take away, but show the passport if you take meals for other people – retirees or some with disabilities,” chat people in the line in front of the FuMi Cafe. They try to speak Ukrainian and prompt each other with the words they struggle to recollect. It is challenging after being Russian-speaking for most of their lives, but “if we don’t start, how will we manage to do this?” It seems Ukrainian retirees have this in common with Fuminori. He endeavors to learn Ukrainian and impresses us with a video message for our Ukrainian readers.

What is your general impression of Ukrainians and Kharkiv residents? I ask Fuminori before we leave.

“You work hard and do not give up until the end.”

“Then you are also a Ukrainian!” I smile at him gratefully.

“I might be a bit,” smiles Fuminori back.

Follow us on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn for more news, stories, and field reports by Kharkiv journalists.