The Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War in Kyiv opened on March 11, 2023, to help Ukrainian POWs and missing soldiers’ families and loved ones. Since a headquarters in Kyiv couldn’t cover the entire Ukraine, regional departments were opened in Mykolaiv, Vinnytsia, Kharkiv, and Lviv.

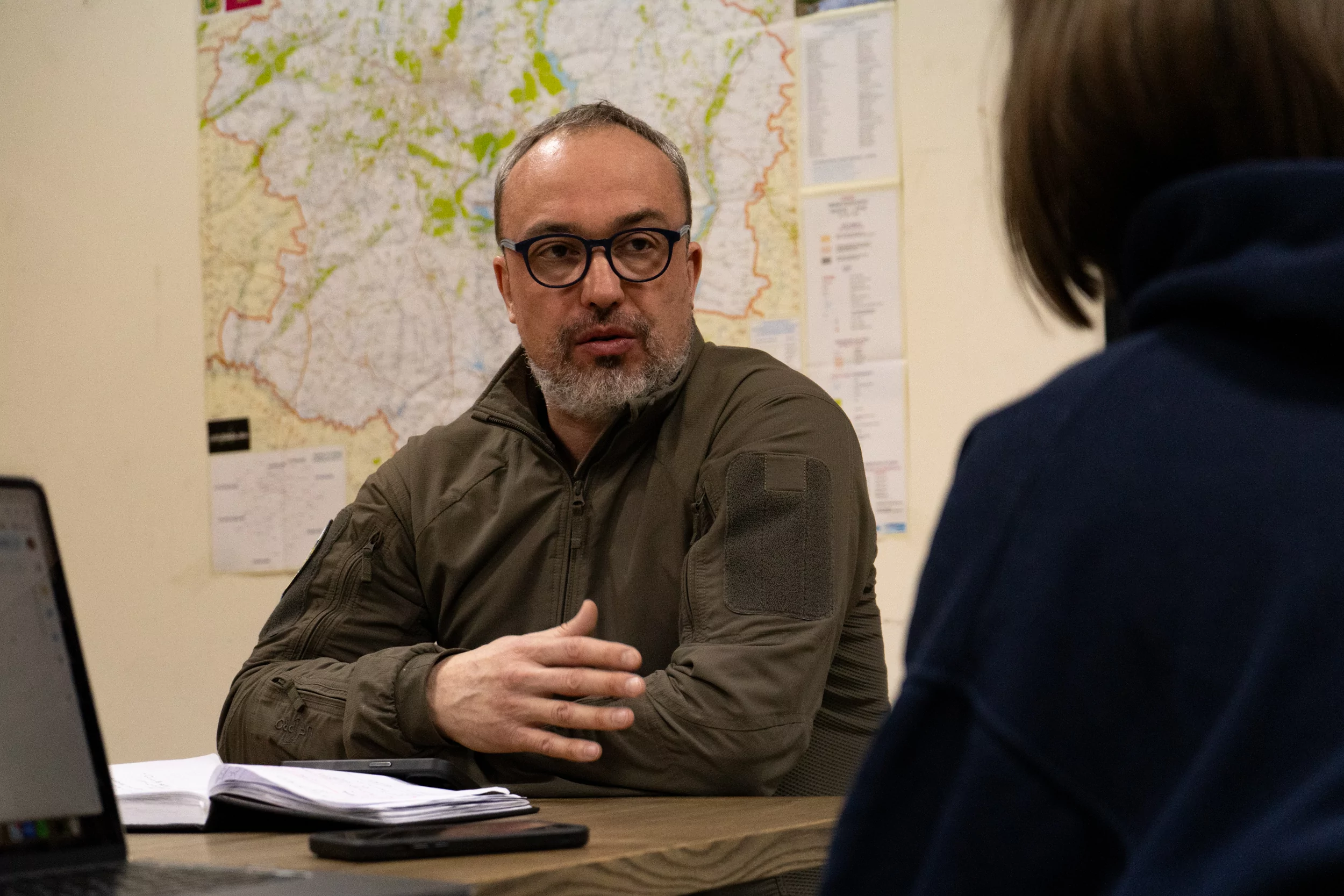

We’ve talked to Serhii Chebyshev, representative of the Eastern Regional Center of POW Coordination Headquarters in Kharkiv, about prisoners of war from the region, HQ’s collaboration with international organizations, and the impact the families can have on the return of their loved ones from captivity. Apart from Kharkiv, the center helps families and loved ones of soldiers in Sumy, Poltava, Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Dnipropetrovsk oblasts.

GM: How does your department of POW Coordination Headquarters work?

Relatives of every defender can create a personal cabinet on our website. HQ’s employees have access to it. The family also can receive information from the soldiers’ colleagues or people who have already returned from captivity and want to share information with the relatives of those who remain there. Relatives also constantly check Russian Telegram channels, where you can sometimes see [photos and videos] of our captive defenders. So, they can add new information to the cabinet: high-quality photos, anthropometric data, and information about tattoos or scars. All of that helps us work.

We also provide legal support to the families. For instance, when a defender and their partner are in a civil union [a marriage that’s not registered by the state — ed.], we help their partner figure out the social guarantees they have according to law. People also ask us about guarantees for children from previous marriages and so on.

We also establish coordination between military units, enlistment centers, and other social services. It’s our main task. Many think the regional center organizes prisoner exchanges, but we don’t. Everything related to prisoner swaps, negotiations, involvement of neutral countries and politicians into exchanges is done by the Coordination Headquarters in Kyiv.

GM. How many POWs from Kharkiv oblast have been returned?

My colleagues and I have a single motivation. When we see a person returned from Russian captivity in our office, it feels so good we want to cry. That’s the only thing we work for.

During the war, Ukraine made 51 prisoner exchanges, bringing home 3,135 defenders. Eighty-eight people from the Kharkiv region have been returned, though this number differs from the real one — the eastern regional center was opened in December 2022.

GM. Can you disclose the number of soldiers and civilians from Kharkiv Oblast that are currently captive?

I can’t disclose it. We can’t say things like that because any information can be used by Russia for its goals.

GM. What is the process of communication between the Headquarters and the family of the captive or missing person?

It all starts with relatives who receive a notice from an enlistment office about a person’s disappearance, death, or capture. No one claims that a person died without a body. Similarly, in the first days of disappearance, no one can claim that a person was captured. When a relative receives the notice, we document the soldier as missing in action [until confirmed otherwise.]

The first stage of working with a person ends when we understand that everything depending on us both is done. Then, a certain pause comes. We’re waiting for a captive defender to be found or returned in future POW exchanges. During this period, people come to us simply to talk because waiting is unbearable.

They often call asking, “Any news?” But, currently, all updates appear in a relative’s personal cabinet online.

Families of people missing in action and POWs often unite and organize to support each other, advocate for their interests, and facilitate prisoner exchanges.

They show that the international community has to act because it really does. The international community has a weighty influence, so it should work to help Ukraine return soldiers and civilians from captivity.

GM. Do families of POWs or families of people missing in action receive financial support?

Soldiers who are missing in action stay accounted for in their military unit, which is why relatives have the right to receive financial support and their “combat” salary.

GM. In which cases families and loved ones receive one-time financial aid from the state?

After being returned from captivity, the POW receives a one-time financial aid of 100,000 hryvnias [~ $2,520]. They also have the right to annual financial support for each year they have spent in captivity. If a person still isn’t free, one of the members of their family receives financial aid for each year their loved one remains captive. Sadly, families of the people who are considered missing do not receive financial aid.

GM. How can families and loved ones of POWs influence the process of freeing them from captivity? Do you have cases like that?

Unfortunately, we’re dealing with Russia, a cunning enemy. We don’t know about such cases yet, but we know about the opposite. When a person is in captivity, for Russians, they are just like all the other captives. Then, relatives or friends start to share information about them on social media…

Russians discover that people know this captive, that they did a lot of useful for Ukraine, that they are a patriot. How do you think, will it make things better for this POW? Of course, the chances of Russia releasing them diminish. Because people are like a commodity to them.

Publicity only hurts our prisoners of war. We warn people against spreading personal information about captives.

GM. People in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv, and other cities are organizing demonstrations in support of POWs. Do you think they can help facilitate the release from captivity?

Demonstrations can urge the international community, ambassadors who remain in Ukraine, and NGOs to work more efficiently towards the release of the POWs.

I participated multiple times. I constantly talk with families there and often face negativity towards the Headquarters. [People say,] “You’re doing nothing to return our heroes home.” We know people are worried about their loved ones who have been in Russian captivity for two years, like Azov fighters. Back then [after the surrender of Mariupol defenders — ed.], Russia promised to return everyone but lied.

Editor’s Note: Over 900 Azov fighters who protected Mariupol in the first months of Russian full-scale invasion remain in Russian captivity. Authorities note that it’s incredibly challenging to negotiate their release with Russia.

Our women are fighting desperately for their boys. They even visited the Pope and went to many countries that tried to be mediators between Ukraine and Russia. These women do an enormous amount of work. That’s why these demonstrations are necessary on any level.

Does the eastern Center of POW Coordination Headquarters collaborate with international organizations?

We have very productive cooperation with, for instance, the International Red Cross Committee. They consult relatives of the POWs and missing people and invite us to participate in programs they create. Cooperation like that helps the POWs’ families. ICRC informs people about the identification of bodies, DNA tests, searching for people, and opportunities for correspondence with prisoners of war… In meetings like these, we share the details of disappearance and information about prisoners of war or missing people.

ICRC in Ukraine works pretty well. They have access to absolutely all Russians who are in our prison camps, control whether they receive medical aid, proper food, or have correspondence. They make sure [conditions] in captivity comply with Geneva Conventions.

We follow all requirements, but the ICRC in Russia is denied access to the prisons. It’s a huge problem: when we know the place of detention of the POW, but Red Cross representatives can’t confirm their status. That means that potentially, the person could be tortured there. Moreover, our prisoners of war aren’t allowed to correspond and don’t receive necessary medical aid.

We constantly talk about this problem on all levels. For instance, the day before yesterday we had a French ambassador here, Dutch Defence Minister before that, other foreign politicians. I see that more people are receiving information about the status of the POWs, confirmed by the Red Cross, but that’s still not enough.

GM. You mentioned that POWs who were released come to you. What do they say about the captivity?

We try to ask them carefully, but they don’t want to remember that. They simply say that it was horrible but don’t share details. I think they want to forget that and live a new life. But if a person weighed 100 kg before captivity and returned with a 40 kg weight, thinned, with chronic conditions and mental health issues, all of us understand that Russia treats our boys and girls very badly.

GM. Media often shows public trials of Ukrainian POWs in Russia. What do you think Russia’s goal for these trials is?

I think these trials are directed at the Russian consumer. Russia wants to show their citizens that Ukraine is a fascist, neo-nazi state. There isn’t even a hint of lawfulness in these trials.

Many women approach me, asking, “My husband was sentenced to 20-25 years in prison. What should I do? Will he be returned?” Trials don’t particularly impact the POW exchanges. Many [people who received the sentence from Russia] have already been returned.

GM. Why are there delays in POW exchanges?

The exchanges aren’t set up to be regular. All of it is very difficult. Sadly, direct communication with Russia, when you can pick up the phone and schedule an exchange in two minutes, doesn’t work. Also, I want to remind you that, according to the Geneva Convention, the POWs must return home only after the combat ends. I think, 3,135 people swapped over two years is a dynamic enough statistic.

Almost all the latest POW exchanges were conducted with the aid and assistance of neutral countries. Sadly, communication between Ukraine and Russia gets progressively difficult, which is why we work through neutral countries for now.

GM. We know about the cases when scammers contact families of the POWs, asking for money to return people from captivity. Do people come to you with this problem?

Constantly. Even when they’re asking for 1 hryvnia, it’s a scam. “Outsiders” that can help release from captivity don’t exist.

The enemy is cunning and does terrible things. There are cases when a wife gets a call from her husband, and the husband says, “Do something to get me out of here.” The woman starts to receive assignments from [Russian] special services, for instance, to film the location of Ukrainian troops in exchange for her husband’s freedom. That’s how recruitment happens.

We recommend families not to talk to Russia, not to provide them with any information, because it creates danger for the country.

GM. Are there special programs or rehabilitation for people returning from captivity?

Everyone who has been brought back is sent to a place, let’s call it a “hotel.” They receive a phone with phone numbers of their relatives; medical care; food. They undergo rehabilitation in this “hotel” for at least a month. When a person starts to feel better, they can slowly, under medical supervision, return to normal life. Boys who visit us here share that the rehabilitation really helps.

Psychological rehabilitation plays an important role as well. Imagine a boy who was taken into captivity at the end of March 2022, somewhere near Kharkiv, and couldn’t talk to anyone who got captured later. Russians pressured him, constantly telling him that Ukraine didn’t exist anymore, that Kharkiv was destroyed, and his family was gone. After captivity, he returns and sees that everything’s okay: the state returns him and cares about him, his wife and kids are safe.

GM. What programs or tools does the Communication Headquarters plan to adopt during 2024?

We have a tool in development. I can’t say we will 100% release it, but we’re working on it tirelessly. I mentioned many Russian Telegram channels with photos and videos of our defenders. The relatives constantly monitor them, searching for familiar faces among the contents, ruining their mental health. Currently, we’re working on a special program that’ll analyze the faces of POWs and match them to the images in these Telegram channels. After finding a match, the system will send out a notification.

In such a way, we’ll be able to find a lot of missing people and save the relatives’ nerves. The system will be AI-based. I think it’ll give us a breakthrough.

Hello. I’m Vika, a journalist and editor for Gwara. I spoke to Serhii to tell you about the struggles of hundreds of Ukrainian families waiting for their loved ones to return from Russian captivity. Thank you for keeping your eyes on this topic. It’d also mean the world to me if you consider supporting our Kharkiv-based media on Patreon, BMC, or PayPal.