More than a year ago, Ukrainians deoccupied part of the Kharkiv region that Russians seized for more than six months. Currently, Ukrainian human rights advocates and international organizations document and investigate war crimes Russians committed during the occupation.

According to the Roma Statute, rape is a war crime. As of September 2023, the Ukrainian General Prosecutor’s Office reported they documented 235 cases of conflict-related sexual violence Russians inflicted on women, men, and children in Ukraine. The real scale of the Russian sexual violence is unknown. Survivors often don’t want to report the rape or come to the police.

Soldiers of the Russian Federation use rape and other types of sexual violence as a tactic of war: to install fear, take revenge, or “punish” the civilians on the occupied territories.

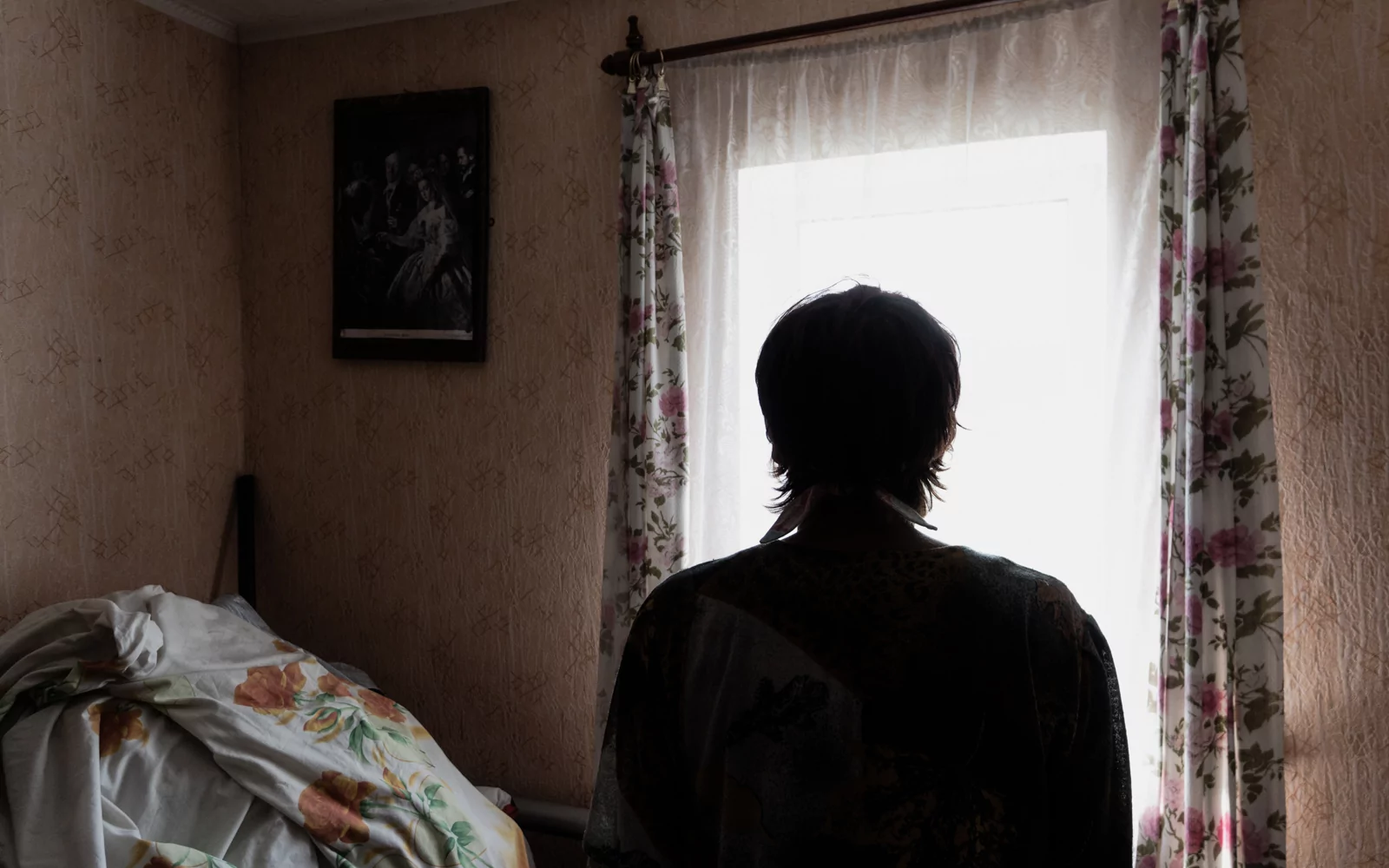

The story of Iryna (the name is changed) is one of the future evidence of Russian sexual violence in Ukraine for the International Criminal Court.

Rape and torture

Iryna is 52. Her husband had died of illness many years ago. The widow lived with her four daughters in her household, but on February 26, 2022, she and her family were forced to leave it. The Russian army was advancing towards her home. One of her daughters managed to evacuate to the other region. Iryna and her three children reached the neighboring settlement. Russians occupied it later.

“They were bombing up when we were running away. Russians were moving in [the village] — there was nowhere to hide.”

Iryna and her daughters started living in the house, abandoned by the owners. For the next six months, the family lived under Russian occupation.

Iryna can’t remember the exact day or month she was raped. She only says it happened at the end of August or the beginning of autumn, sometimes close to deoccupation. Iryna was home with her youngest daughter when Russian soldiers came to her house.

“In the evening, three Buriats entered the house, so I closed my youngest in the closet. A pan with fried potatoes was on the stove, and about ten cucumbers were nearby. They took everything, ate, drank two bottles of vodka. They smoked right in the room and threw cigarette butts on the floor. I stood near the doors when one of them came close and threw me onto the bed. At least he wore a condom. He was beating and raping me for four hours until the blood started to pour out.”

“The more I screamed and asked for help, the harder he hit me.”

Iryna couldn’t ask for medical aid because hospitals didn’t work under the occupation. The woman had to lie in bed through the bleeding. “I remember my head spinning very hard, but thank God it was over. I wanted to report [the rape], but [to whom?] No one wanted to listen.”

“I stand up and [see] a bloody mess between my legs,” Iryna says, “he tore everything apart.”

The woman rolls her shorts up and shows the scars on her legs, left by occupiers. Apart from rape, Russians tortured her.

“Russians put me against the wall and interrogated, “Where are the ATOvians?*” But I didn’t even know if they lived here because I wasn’t local. So soldiers threw knives at me and shot at my legs. Since then, there are scars on my body.”

*Editor’s note: Ukrainian soldiers who fought in the Russian-Ukrainian war before February 24, 2022. See Anti-Terrorist Operation Zone.

What conflict-related sexual violence is

We asked Maryna Sviridova, a jurist from Jurfem, Ukrainian Women Lawyer Association, and psychologist of the Avrora platform, Maryna Syritsia, about conflict-related sexual violence and how it’s documented.

Conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) is a war crime and often a part of a deliberate military tactic that aims to weaken and destabilize civilians and establish authority. In Ukraine, CRSV is prosecuted under Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine as a violation of laws and customs of war.

Documented survivor’s accounts are a basis for the prosecution of perpetrators and the restoration of justice. A person can report the crime when they are ready, even years after the crime happened.

Conflict-related sexual violence differs from crimes against sexual freedom and integrity. In the latter case, rape is characterized by the absence of consent of the survivors. However, if armed people are trying to get into a person’s house and the person opens it on their own, it cannot be qualified as “consent.” In the circumstances of the armed conflict — when the survivors are unable to give true consent under pressure when the refusal to engage in sexual activities can be deadly — sexual activities, even without the indicators of coercion, can be qualified as sexual violence and rape.

Rape is the most severe form of sexual violence, but CRSV isn’t limited to rape — it’s any sexual activities occupiers or perpetrators involve civilians in, no matter civilians’ age or sex. The term includes rape threats, mutilation of genitals, sexual slavery, in particular marriage slavery, forced abortion, forced sterilization, forced pregnancy, forced prostitution (e.g., women having sex with Russians to get food and protection), and other forms of “sexual violence of comparable gravity.” Forced nudity is also included in the umbrella of conflict-related sexual violence. In Ukraine, during so-called “filtration” — “security check” Russians create for civilians who want to leave or are forced to leave occupied territory — they force people to get naked not only to search for tattoos with the Ukrainian flag or coat of arms but to humiliate, make them lose dignity.

How do you talk to survivors of sexual violence?

The experience is hard to talk about, which is why survivors often choose to remain silent and avoid conversation. They can behave differently: be sad, apathetic, or even aggressive. Respect the complicated experience they’ve gone through and keep yourself from advising them or trying to save them. Ask: “What can I help you with?”, “What do you need right now? Can I be useful in any way?”

Create a safe space. Don’t ask what happened and how not to launch a stream of traumatic memories. Don’t touch, hug, or wrap a person in a blanket without their consent. If you want to offer a blanket, just put it near them — offer choices to return them a feeling of control.

If a person behaves aggressively, don’t tell them, “Calm down,” “I understand what you’re saying, come on,” or “Stop swearing.” When people are told to calm down, they get even more aggressive. What can you say? “I’m listening, keep going” is a good option.

Talk calmly. You can also take a walk with a person, so they’re able to talk — and move — through what they want to say. With each step, slow the pace of the walk down to reduce the level of aggression. Give them space, and don’t take what they say personally.

Note that UNHCR recommends not to actively seek out people who have experienced CRSV and not to ask people if they’ve experienced sexual violence. Read the guide on how to document CRSV here.

Read the article in Ukrainian for contact information on services survivors can utilize to report CRSV or seek help here.

Author: Vika Mankovska

Translation & editing: Yana Sliemzina