On July 28, the Russian military shelled one of the premises of the former penal colony, now a Russian-operated prison near Olenivka, situated in Russian-occupied Donetsk oblast. The explosion killed about 40 Ukrainian soldiers. Still, there are many Ukrainian prisoners of war left there in Olenivka. We spoke with the relatives of one of them. They still do not lose hope, despite the inaction of international organizations.

Yurik, an anesthesiologist, was rescuing Mariupol people. Since April, he has been in Russian captivity. For a long time, nobody got a clue that he and many other medics were captive. Yurik’s sister Karina agrees to talk about her brother but stresses that her goal is to help all the doctors return home.

Karina and Yurik Mkrtchyan were born in Armenia. They moved to Ukraine with their parents. Since the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian war in 2014, they fled to Kyiv. Later, Yurik was assigned to work at the Dnipro [a city located in the eastern part of Ukraine bordering Donetsk oblast] hospital and went there with his wife.

“He always dreamt of becoming a doctor. Our father died early, and Yurik decided his dream should come true. Next, our grandfather died because of medical malpractice. Yurik was finishing his third year of studies and was shocked with such an attitude of doctors toward patients. Since then, he vowed to save every life he could,” says Karina.

Before retraining as an anesthesiologist in 2021, Yurik had been a surgeon. Also, he holds the title of lieutenant of the medical service. Yurik realized the war was near and made an action plan. Karina started preparations a few months before the war, too, although she did not want to believe it.

“Kyiv woke up to explosions on the morning of February 24. I called my mother and brother immediately. My brother was asleep, so he didn’t hear anything. But he was not surprised. Not at all. I asked, ‘What will happen to you? Where will you go?‘. He said he would act according to his plan and go whenever necessary,” Karina recalls.

Yurik was at work during the following weeks. Over the phone, he was constantly convincing Karina he was still in Dnipro. He said that everything was fine, although there were many wounded. Karina highlighted his fearlessness and moral strength. She was anxious but hoped he was indeed away from the battlefield.

“I am worried about him. I want him to come back. He should save people, not waste his time behind bars,” Karina says.

Karina started volunteering with her boyfriend and her sister-in-law. They collected the meds needed in Yurik’s hospital. She was trying to find out whether he was really residing in Dnipro.

“He said, ‘Don’t ask me; I won’t tell you. I’m fine.’ Later, we found out he was neither in Dnipro nor in Mariupol. He was somewhere in the Dnipropetrovsk oblast,” she says.

Karina does not know when exactly her brother got to Mariupol. She reassured herself Yurik was far from the hotspot if he still had an opportunity to call.

“Then, one day, we could not reach him over the phone. Instead, he started texting us every two or three days. It was clear he had gone somewhere. Probably it was late March when he was sent to Mariupol. Together with other doctors from Dnipro, he flew in a helicopter to help his colleagues,” says Karina.

Yurik reported about his whereabouts in early April. There was no connection, so he went on texting online. He asked not to tell his mother about his location. Mostly he communicated with his wife, and Karina received messages like, “Everything’s all right. Don’t worry. Say hi to mom. Love you all.”

“He said there were many people under the debris. Also, sometimes they had only one piece of bread and a glass of drinking water for all the patients and doctors. There were tough living conditions,” Karina says.

One day Yurik finally called her. He was at the Ilyich metallurgical plant. He confessed the situation was critical: he may end up in captivity.

“We couldn’t reach him since that call. On April 13, we started flooding all the hotlines we could find. We submitted requests and documents. Then we received a response from the state. So, we weren’t idling about,” says Karina.

She found out her brother was in the temporarily occupied Olenivka, a colony in Donetsk oblast. She came across a video on the Russian Telegram channel with doctors providing medical aid to prisoners. Among them was Yurik.

“It happened in May. However, we had already known he was in Olenivka. Earlier, his wife had received a message from an unknown number, ‘Yurik is in Olenivka. In captivity. Alive.’ The sender deleted that message almost right away after we read it,” Karina recalls.

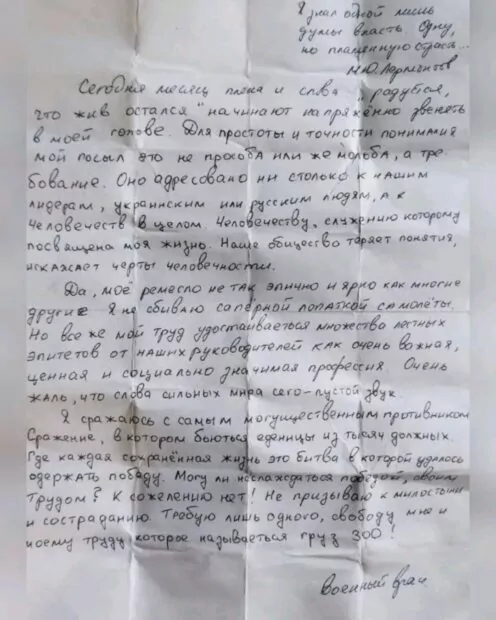

There was another piece of news from Yurik. His wife received a photo of a handwritten letter with the signature “military doctor.” There he asked neither to reply to the message nor to call back.

“We never thought to write or call back. We realized it was from Yurik, but we didn’t know the sender. We don’t ask unnecessary questions. Yurik wrote a letter for the sake of saving others as well. He asked to rescue the wounded,” Karina says.

According to Karina, there is a pregnant woman among the captured medics. She needs help firsthand. She went to Mariupol to rescue people, not knowing she was pregnant.

“We can see from this letter that there is no proper medical care from the captors’ side. People die. Even under such conditions, our doctors take care of patients. Having received this letter, my sister-in-law and I decided we must speak up. Russia commits crimes, disregarding all moral rules and human rights,” says Karina.

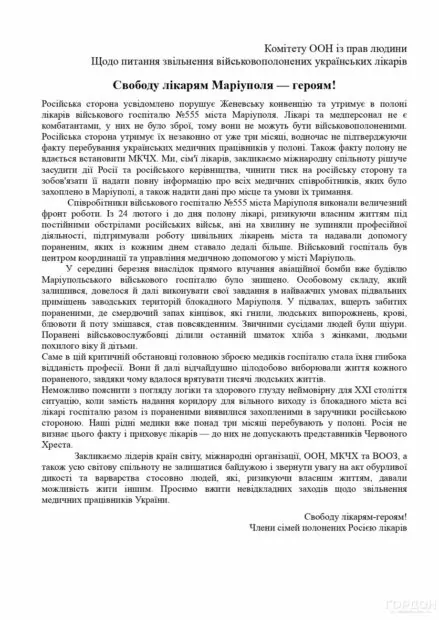

In May, Karina sent a request to the UN, attaching Yurik’s letter to it.

“Some person called me, expressed his condolences, but said it was not their competence to release captives. He proposed to address the Red Cross. Their employee called me and offered to open a case about my brother. I asked him to do the same for other doctors as well. It was our first and, unfortunately, the last conversation with the Red Cross,” Karina says.

On July 29, the Russian military executed more than 50 prisoners of war, shelling one of the premises of the Olenivka colony. Several sources confirmed that Yurik was alive after the terrorist attack. Other medics survived, too. They are all still there in Olenivka.

Karina is currently in contact with various human rights organizations. However, her appeals remain ignored, “We have received your request and kindly ask you to wait as we have a lot of work.”

“We tried to reach the Red Cross with the help of lawyers. In turn, they refused to give any information to the lawyers, for they were not relatives. It’s strange: I am a relative, but I got no answers either,” says Karina.

Karina got close with other relatives of the captives. She says that in such a situation you try to look for at least some hooks, ask people, join the chats.

“My sister-in-law contacted some people. She found out Yurik was flying to Mariupol with Dmytro, also a doctor. She contacted Dmytro’s wife. Eventually, there were 60 people looking for their loved ones,” Karina says.

In besieged Mariupol, under shelling and bombardment, it was medics who saved people. Now we must rescue the medics themselves, speak and remind everyone about them.

“They are considered rearguards. In fact, they are always on the front lines. My brother wrote they were saving lives and fighting against the most powerful enemy, which is death. Why was there no green corridor for the medics? Society knew nothing about them at all. Now, all the relatives of the captured are one big family. We will fight for each of our loved ones,” Karina says.

Text by Maria Masiuk

Translated by Yulia Kulish

This material was developed by Gwara Media as part of the IWPR program “Supporting regional media of Ukraine during the war” with the support of the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Great Britain.

The content of the material is the sole responsibility of Gwara Media. It does not reflect the views of the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Norway, the United Kingdom Government or the Institute for War and Peace Reporting.