“I want to set an example for my child.” “I identify myself as Ukrainian.” “I don’t want to hear Russian again.” “I love Ukrainian.” “I know several supermarkets where they only speak Ukrainian, so I go there just to chat.” “I study the language by songs.” “I read only in Ukrainian.” These are the stories of people who switched to Ukrainian in one of the most Russian-language Ukrainian cities, Kharkiv. We asked about their motivation, and the difficulties they face all the time.

Switching to Ukrainian when you have been speaking Russian for your whole life is not the easiest task. After all, most of your emotions and feelings you have experienced in the other language. Therefore, even if you know Ukrainian, it is difficult to speak fluently right away.

To improve communication skills, numerous courses, textbooks, workshops, marathons, and speaking clubs have been created. One of them was opened in Kharkiv, and Gwara Media journalists have visited its classes.

What happens in the speaking club?

The class is moderated by Nataliia Karikova, a Ukrainian language teacher at the Simon Kuznets Kharkiv National University of Economics. She has been working at the university for over 10 years.

The speaking club, as always, begins with getting to know the participants. Many people gathered here, some even came with children. The class, divided into theoretical and practical parts, lasts for about two hours. First, Nataliia speaks about social projects. A language club is an initiative of one or more people who have come together to make a difference. “We have to take the initiative into our own hands and do something,” says Nataliia.

“If I have free time, know the language, I can speak it, maintain contact with the audience and organize, then I will join the initiative,” explains Nataliia when asked about how she became the speaking club moderator.

One of the homework assignments for the club members was to listen to audiobooks in Ukrainian and share their experience. Interestingly enough, the majority chose “The Kaidash Family” by Ivan Nechui-Levytskyi [a prominent Ukrainian writer – ed.]. So at some point, the speaking club turns into a book club.

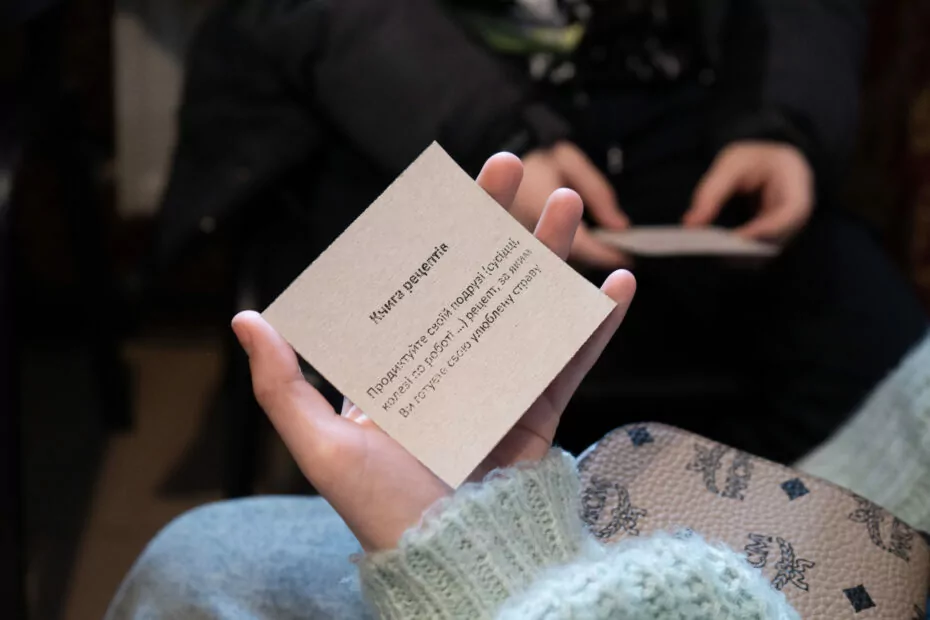

Later, the group discusses which Ukrainian words can be used in everyday life, how to order coffee in a coffee shop, warn the driver about a stop, or buy something in a store. Then comes the practice: club members speak with each other.

Since this is not a formal lesson or lecture, the club takes place in a cozy room without desks, but with coffee, tea, and the support of the moderator and participants. Like-minded people have gathered here, their common goal is to leave the class and communicate in the proper Ukrainian language.

Stories of people from the speaking club

Iryna Semenova, 43, works in sales

“Actually, our language is so beautiful. I like it when people speak Ukrainian well. I would also like to talk freely, but it has always seemed to be not the right time for that,” says Iryna. “Although I studied at a Russian-speaking school, we learned Ukrainian grammar and literature. I understand it, but it is difficult to speak.”

Iryna says that at times a language barrier arises when she cannot quickly find the right word, so she switches back to Russian. At the same time, the woman continues to practice. She answers in Ukrainian in stores and communicates exclusively in the state language on social media. “Messengers are a bit easier. When I don’t know a certain phrase, I can look it up and have more time to write a good answer or a comment.”

Iryna’s daughter motivates her to learn the language. “I have recently come across my daughter Daria’s homework, she is 10 years old. The task was to write why we, the Ukrainians, should speak Ukrainian. The daughter wrote that we knew our native language, but we didn’t have to speak it. We can speak any language for convenience, so she will continue speaking Russian because her friends also speak Russian. These words made me feel so sad. I can’t set an example for her because I don’t speak my native language myself.”

Finally, Iryna talks about her past vacation in Turkey, where she met a Turk who studied in Kharkiv and knew several languages: Turkish, English, French, German, Ukrainian, and Russian.

“Then I thought, it is so strange that we live in Ukraine and do not speak the national language. The pieces of the puzzle came into place in my mind. Then a full-scale invasion began — and with it, the confrontation with everything Russian,” adds Iryna.

Viktoriia Kravchenko, 35, a private teacher

“Before the full-scale invasion, I was more lenient to the Russians and their country in general. But after it affected me personally, I realized: something needed to be changed,” says Viktoriia. “I have an apartment in Northern Saltivka [Kharkiv neighborhood, one of the most affected by Russian attacks – ed.], I have just bought it and I lived there for six months. I was going to get married and start a family, but all my plans were destroyed by the Russians. That’s why self-identity became important, and I’m Ukrainian.”

Viktoriia admits that she knows Russian better than Ukrainian. It is difficult for her to communicate fluently in public because sometimes she does not understand certain phrases. Therefore, Viktoriia decided to fix it by improving the state language communication skills in the speaking club.

“I like to learn new things, so Ukrainian is a new challenge for me. Not always everything works out from the get-go, but at least you have to try. Just imagine me having a child, but being unable to help them with the homework – I will feel ashamed.”

What is the most difficult thing about switching to Ukrainian?

— Many words in my speech are derived from Russian, because I studied at a Russian-speaking school and spoke Russian. And in general, it was rare to hear Ukrainian [in Kharkiv — ed.]. But now there are many good Ukrainian musicians whom I constantly listen to, and it helps to strengthen my skills.

Do you have favorite musicians?

— I like Artem Pyvovarov [modern Ukrainian new-wave pop musician from Kharkiv Oblast – ed.], he has a heart-touching voice and strong lyrics. Also the Shablya band — I really like the song “And the sun will rise” [Ukrainian cover of Rammstein`s Sonne – ed.]. When home alone, I turn it on and sing along. I think that I am even good at it (smiles). If we talk about the songs, then I know Ukrainian well. Even before, when I went to karaoke, I always chose songs in our language because I thought they were better.

Valeriia Vitaliivna, 60, a teacher

“I have been trying to switch to Ukrainian for a long time. Since I work in a kindergarten, I conduct classes with children in Ukrainian. But as soon as the classes were over, everyone around me started speaking Russian, and I automatically switched to it too. After the full-scale invasion, I went to the west of Ukraine with my family, where we finally immersed ourselves in the Ukrainian-speaking environment,” says Valeriia. “In 10 months, I have succeeded. I no longer switch to Russian and do not stop at what I have achieved, I try to improve my vocabulary. Sometimes I speak surzhyk, but then I immediately use Google Translate to see how to say it correctly in Ukrainian.”

According to Valeriia Vitaliivana, when she returned to Kharkiv, it became more difficult to continue communicating in her native language due to the Russian-speaking environment. Although she continues speaking Ukrainian at home, her colleagues at work and neighbors keep speaking Russian.

“I hear that my speaking skills have degraded, and surzhyk appears more and more often. That’s why I decided to go to a speaking club to expand my vocabulary and bring Ukrainian to the masses. I am very happy when my friends switch to Ukrainian while talking to me. For me, it is a small victory,” confesses Valeriia Vitaliivna.

To practice the language, Valeriia Vitaliivana likes to go to the Rost [chain supermarket in Kharkiv – ed.] near her house, because all the employees there speak Ukrainian.

Viktoriia Shcherba

“I switched to Ukrainian in 2014. I started by completely giving up Russian-language content, then began reading books and posting on social media in Ukrainian. My family supported me and spoke our native language as well. But I continued to speak Russian at work,” says Viktoriia about her experience. “On Feb. 24, I realized that I had to start speaking Ukrainian, so I came to the speaking club. My goal is to go out and communicate in my native language in public.”

What is the most difficult thing for you in practicing Ukrainian?

– The most difficult thing is to start talking. Over the years, I have improved my vocabulary, but the automatic switch to Russian is very disappointing. When speaking quickly, I switch to Russian. But this can also be overcome. When I wove camouflage nets, there were girls with me who spoke only Ukrainian. Some addressed them in Russian, but they did not switch to another language. It motivated me and helped me to continue speaking Ukrainian.

The most frequent problems people face switching from Russian to Ukrainian

We could not miss the chance to chat with the moderator Nataliia, so we asked her a few questions as well.

– Talking about pronunciation problems, it is the Russian letter “Ґ” [the sound [g], while in Ukrainian [Г] is similar to the English [h] in ”hot” or ”happy” but voiced and pronounced with greater energy – ed.] that appears most often in people’s speech. It is interference, the influence of the dominant language, as Russian has been dominant in our country for more than a century.

It is very difficult for people to overcome the language barrier because they are used to a Russian-speaking environment. As an example, today the participants of the speaking club said that Kharkiv is a Russian-speaking city. But it seems to me that the number of Ukrainian speakers has increased now. People deliberately began switching to Ukrainian, because they consider Russian to be the language of the occupiers, and here I completely agree.

At the same time, when a person is consciously ready to switch to Ukrainian, a language barrier still arises. There is a simple lack of vocabulary, words that can be used in everyday life. That’s why people can’t talk about more abstract concepts or don’t even always know how to say “bread” in Ukrainian, order some service, or how to properly use elementary etiquette formulas, such as “excuse me”, and “please”.

How to fix it?

— First of all, listen to audiobooks, it helps. Read more so that you can see the text, this will help expand your vocabulary. Secondly, to speak freely, you need more practice, so participate in such activities, and invite your friends.

Do you believe in the widely spoken Ukrainian language as Kharkiv`s future?

– To be honest, before the war, I thought that Kharkiv would not become a Ukrainian-speaking city during my lifetime. But now, with the full-scale Russian invasion, it seems that this will speed up the process. What we see is a very serious push for Kharkiv to finally switch to Ukrainian. It will definitely happen in the nearest future

The speaking club takes place thanks to the Yedyni (“United”) movement. This is a large-scale motivational project that provides educational and psychological support in the transition to the Ukrainian language for Russian-speaking Ukrainians, in particular for the displaced persons. Their goal is to restore the identity of Ukrainians and unite them through the language.

The movement has several directions: a free online course, psychological and technical support, speaking clubs in various Ukrainian cities, lectures, and webinars by experts, etc.

In Kharkiv, speaking clubs take place at the locations of the Yellow Aid Charitable Foundation. The organizers said that it was very easy to find members for the club in Kharkiv. Information about its opening has just been spread, as 300 citizens have already registered. Currently, speaking clubs work in two locations, the library and the assistance center of the CF Yellow Aid.

Also read Slava Ukraini: How to Say Glory to Ukraine in Ukrainian

This material was created with the support of the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). The content of the publication does not necessarily express the opinion of EED and is the sole subject of its authors, the editors of Gwara Media.

Text by Dasha Lobanok

Translated by Alisa Yarova

Edited by Tetiana Fram

Follow us on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn for more news, stories, and field reports by Kharkiv journalists.