After the USSR failed, some political parties and republics forbid the symbols and ideology of communism. Chech Republic, Georgia, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, and Ukraine.

All of the countries are interested in their way to independence, so their culture has been developing over the last thirty years. In our particular project dedicated to the 30-th anniversary of Ukrainian independence, we explore the ways of Estonia, Poland, and Ukraine – the neighbors, the partners, the friends.

Poland after the collapse of socialism

Although Poland did not belong to the Soviet Union, it was a member of the Warsaw Pact, a military-political union of eight communist states wholly subordinated to the USSR. On July 1, 1991, a protocol of its liquidation was signed in Prague. However, the transformations in Central Europe caused the treaty to die out many months before its formal abolition.

After the collapse of socialism, the Polish economy’s main problems were hyperinflation, which in 1990 was more than 600% per year, and the deficit resulting from an inefficient and politicized system of manufacturing in the Polish People’s Republic.

The Polish economic miracle would have been impossible without reforms that shifted the economy from a faulty central planning model to Western capitalism.

On January 1 of 1990, the post-communist Polish government introduced one of the most far-reaching and radical economic reform programs ever undertaken in any country during the XX century. It quickly transformed a communist economy based on central planning and state ownership into an economy with the market allocation of resources and largely private ownership, the Balcerowicz Plan, named after Finance Minister Leszek Balcerowicz.

The minister thought to do many things at once: significantly reduce the runaway rate of inflation (which was as high as 50% per month); decontrol most prices; eliminate shortages; make the Polish currency convertible into other currencies at market rates; cease the subsidization of state enterprises; and remove most restrictions on foreign trade.

Because of the speed and scope of the reforms, the impact on Polish markets and enterprises was immediate and profound. Remarkably, the program’s main goals, widely known as “shock therapy,” were achieved within a few months.

In the 1990s, the country was recovering after Balcerowicz’s “shock therapy,” totally focusing on political and economic reforms. And only at the beginning of the new millennium country did the situation start changing radically.

The global transformation process in the country began in 1989, but it took a long time to reach a qualitatively new level. “For the first ten years after 1989, we adapted the cultural field to the processes of decentralization and the free market. It was essential to take advantage of the ideological role of governance. Still, the fundamental transformation of the cultural sector began later, “said Katarzyna Pudlo, project coordinator for the municipal cultural organization Warsztaty Kultury. The first public discussion on cultural reform came out only in 2000.

The beginning of Poland cultural Transformation

In 1999 the Ministry of Culture initiated a new cultural policy program, the goal of which was to promote Polish culture abroad. An agreement was signed with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, responsible for Poland’s external cultural relations.

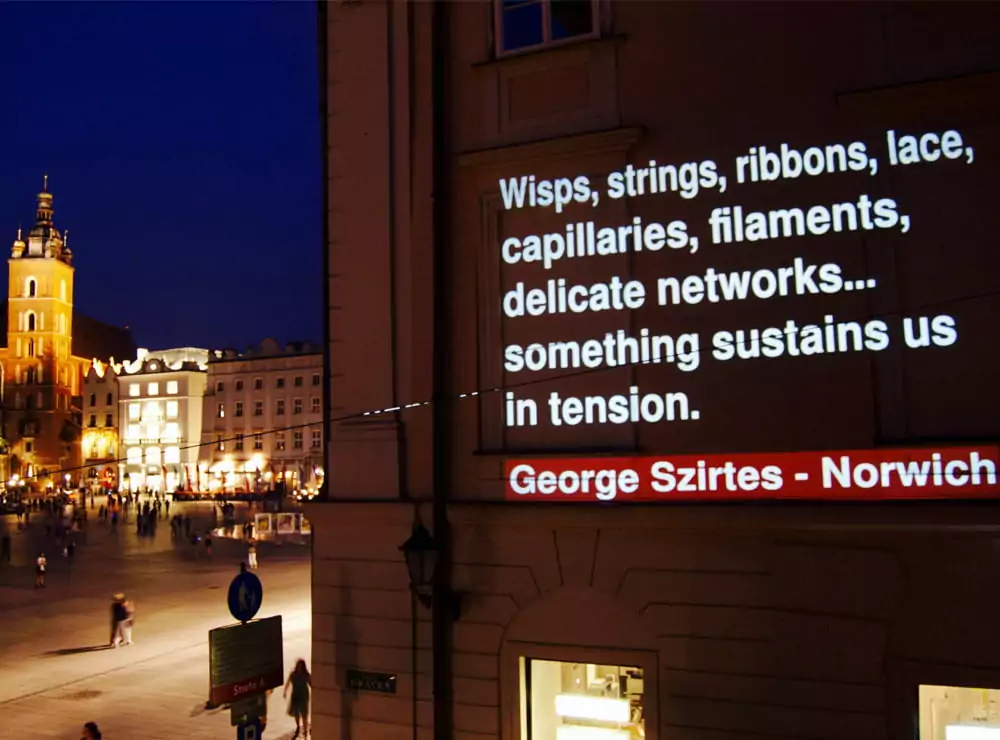

For instance, in 2000, Kraków was named the European Capital of Culture, and in 2013, at a conference in Beijing, Krakow was officially declared as a UNESCO City of LiteratureUNESCO City of Literature. Krakow became the first Slavic and second non-English-speaking city in the world to be awarded this prestigious title. The city authorities are constantly concerned about the organization of various festivals, literary walks, book fairs, writing courses, and projects related to promoting reading culture among children and adults.

Such pressure is “accompanied by the belief that literature can help improve social ties, stimulate economic development and the development of creative industries, significantly affect intercultural dialogue,” cites the city’s website the city’s website.

By the way, Krakow is tolerant of migrants and is an excellent example of a multicultural city where foreigners can participate in the city’s cultural life and speak about problems or ideas in their voices.

In the last three years, Polish literature has again become a hot topic in the West, as in 2019, Olga Tokarchuk was awarded the Nobel Prize.

As a result of active cultural reforms, in 2001, Poland became a permanent participant of the EU Culture 2000 Programme, which aims to support cultural cooperation between the participating countries. Currently, Poland has 21 institutions engaged in overseas dissemination of information on the country’s history, culture, social life, and scientific and educational potential.

Moreover, in 2000, the Adam Mickiewicz Institute in Warsaw was founded. It’s an essential organization for the promotion of culture. Over the years, the Institute has implemented seasonal and annual Polish cultural projects in twenty-six countries. In addition, the Institute launched a sizeable trilingual portal on Polish culture Culture.

Nowadays, the Polish cultural policy model is characterized by a high level of decentralization, which emphasizes local governments’ critical position and role. For example, the 1990 Law on Local Self-Government states that the responsibility for libraries and other institutions aimed at the local dissemination of culture should be vested in local self-government bodies. Therefore, it is not surprising that you can go to several festivals within one province when traveling on weekends in summer. Gminas (administrative units in Poland) organize harvest festivals, potato festivals, village days, or folk festivals on different occasions. The local housewives bake regional pastries or prepare local dishes. Of course, at first glance, this may seem simple. Still, in this way, the country develops a sense of belonging to the community and an understanding of the importance of folk traditions, which later affects the development of high art.

50 years of arguments

There is an excellent example of a process that describes the cultural transformation in Poland in general. It is a building that anyone who has ever visited Warsaw may remember 一 Palace of Culture and Science. After World War II, the Soviet Union built a vast building to emphasize its relationship with Poland. A Polish delegation of architects went to Moscow, where they found out that almost everything about the building had already been decided:

- it was to be built in the style of Stalin’s Gothic,

- construction was to be financed and carried out by the USSR,

- for the most part, materials from the USSR were to be used, and Soviet builders were hired to carry out the work.

The Polish government only had to determine the exact location in Warsaw where it would be built and how it would be used. The palace’s building lasted from May 1, 1952, to July 21, 1955. The building did not fit into the architecture of Warsaw and dominated the city’s urban landscape, making it the most controversial building in Polish history. Some people saw the palace as a sign of Soviet occupation rather than a generous gift. Others were convinced that the resources used to build it could be better used to rebuild Warsaw that was ruined after WWII.

Due to the inconsistency with the local architecture, the palace received ironic nicknames such as “beet in the cake” or “monster from Warsaw” due to its resemblance to a giant cake – “the dream of a crazy confectioner.” The house was called “PEKIN” (because of the abbreviation of its full name in Polish – PKiN) or “Pajac” (which in Polish 一 clown; the words pałac and pajac sound similar in Polish).

Today, the palace is no longer named after Joseph Stalin, but ironically, it has become one of the capital’s most famous buildings and symbolically. The Palace hosts exhibitions and fairs, the restaurant on the 30th floor, the Collegium Civitas, four theaters, a cinema, and an indoor pool. Many foundations are occupied by city offices and offices of several private companies.

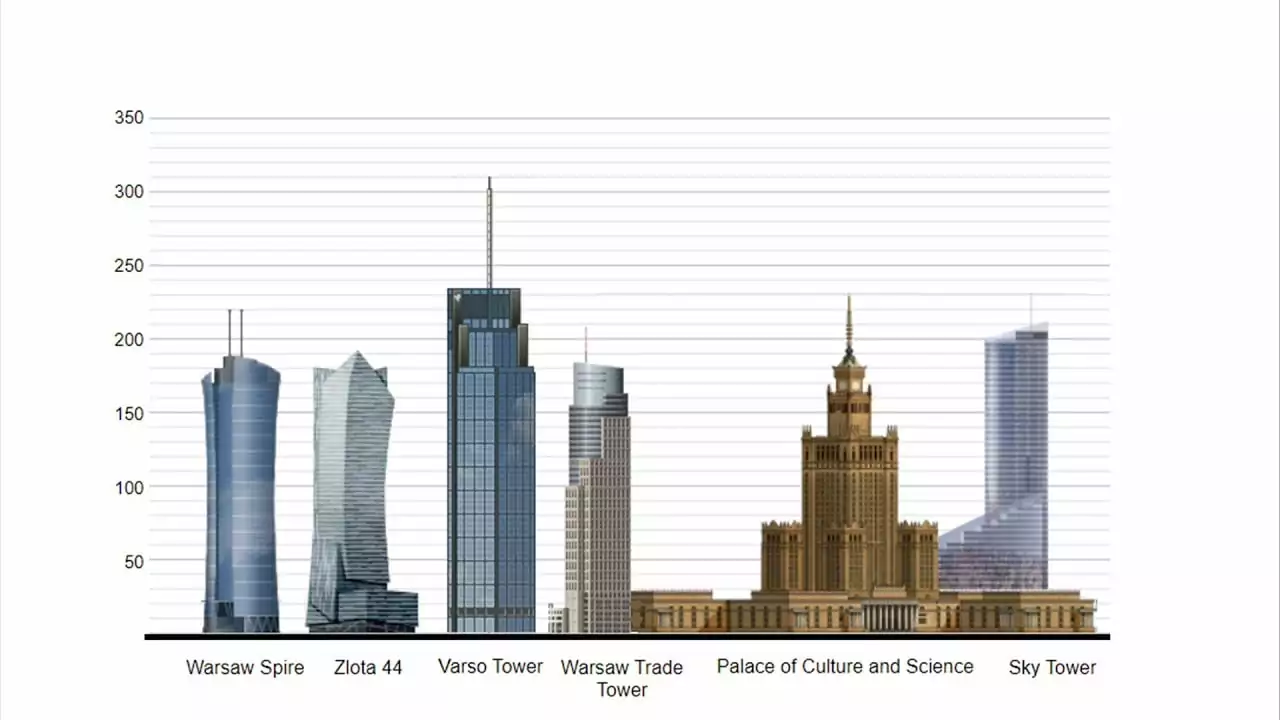

The many groups that wanted to demolish it after the fall of communism, the few businessmen who wanted to buy it, nevertheless the fact that Taiwanese architects tried to cut it into four pieces and move them to other parts of Warsaw, the palace stands where it always stood. It is still visible in many parts of the city. Soon the house will no longer be the tallest skyscraper in Poland. The construction of the Varso Tower (310 m) is nearing completion in Warsaw, which will finally take the crown from the clown and become the tallest building in the country and the entire European Union.

Creative industries. Video Games as Poland’s business card in the world.

All reforms in the economy and culture have led to the country becoming a significant producer of creative goods and services. Today, Poland is the seventh-largest producer of games in Europe and the 23rd world.

The Games are an essential branch of the Polish economy. In recent years, the most popular sector among investors on the Warsaw Stock Exchange has been a clear advantage for gaming companies. According to the report “The game industry of Poland,” in 2019, sales of Polish games exceeded 2.1 billion zlotych. 96% of sales are exported. Currently, more than 440 companies produce matches in the country. Every year, players receive about 480 new Polish games.

The history of Polish game development should begin with Adrian Khmelyazh, who and Grzegorz Machowski founded Metropolis Software in 1992. New serious players later grew: People Can Fly and 11-bit studios. PCF has created, in particular, the famous games 一 Painkiller and Bulletstorm (along with Epic Games).

Poland’s most significant game manufacturers are CD PROJEKT, Huuuge Games, and Techland. The first of them created the best Polish game, 一 The Witcher. In a series of games, as in the books about the Witcher Andrzej Sapkowski, important motives are racism and xenophobia towards “non-humans” forced to live in ghettos, politics, and negative attitudes towards magicians and magic, mainly by religious fanatics. The most significant success was The Witcher 3, released in 2015.

Kuba Bobrovich, a gamer who has played for over 20 years currently works in the game dev field, says:

“It is clear that efforts have been made here. They even hired professional actors to voice the characters. The developers also tried to introduce topics that were taboo for Western games. They are not afraid to show erotic (but not pornographic!) Scenes boldly talk about racism and portray the world, not black and white. In the game, you never know what is good and evil. We always decide on the protagonist of The Witcher 3, which has consequences, as in real life.

More and more producers, inspired by the success of “The Witcher,” decide to engage in games from the AAA segment, i.e., with a large budget and production and promotion.

The Polish Game Association, one of the largest and most well-known game developers in Poland and working with representatives of the Polish government, claims that “the local game development industry has become a source of national pride.” This is evidenced at least by the situation when in May 2011, during his visit to Poland, Barack Obama received from Prime Minister Donald Tusk among the gifts that are recognized as representative of the country, “The Witcher 2”. Three years later, in Warsaw, Obama mentioned a gift and stressed that it was “a great example of Poland’s place in today’s global economy.”

Video games have become one of Poland’s national intellectual specializations, leading to many state aid programs to increase the country’s global competitiveness further.

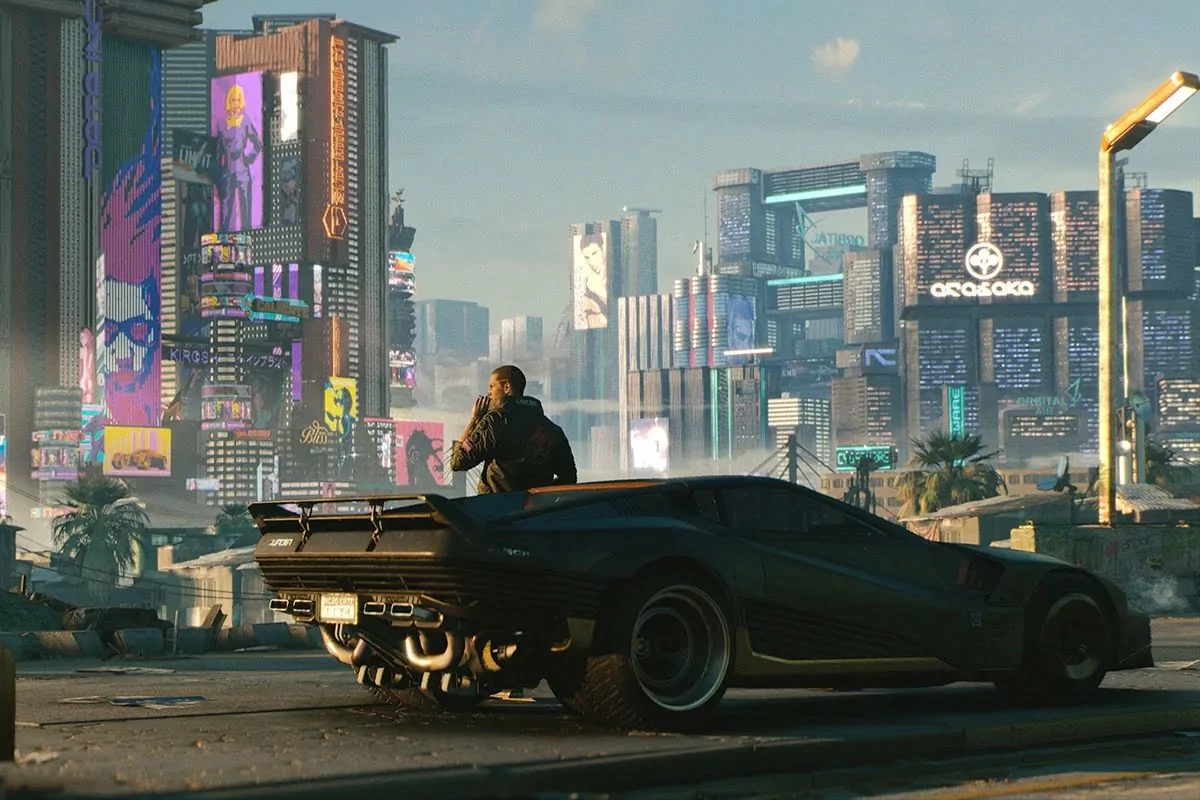

In addition to The Witcher, CD Projekt also created the most expensive game in the history of Polish gaming 一 Cyberpunk 2077, which cost more than 315 million dollars. 45% of this amount was used for marketing. But according to Cuba, the much-anticipated premiere a year ago did not live up to expectations.

“Cyberpunk is an aesthetic game, with an interesting plot, but it’s nothing when there are a lot of bugs, and it’s hard to play,” explains the gamer and hopes that soon the studio will correct all the technical errors, and in 2022 will release an updated version of the game. So far, it is known that Cyberpunk 2077 has collected more than 21,000 positive reviews on the Steam service after the release of patches.

Another diamond due to Polish gamers and creators is Dying Light, made by Techland. By the way, the premiere of Dying Light 2 Stay Human is scheduled for February 2022, which can also be a great success in the world.

This War of Mine (2014), developed by 11Bit Studios, also had a large circulation. The peculiarity of this game was, in particular, that it allowed feeling not as a soldier in the war but as a civilian trying to survive.

“In Polish gameplay, we don’t just shoot, we also raise more serious, deeper topics,” explains Cuba.

Another proof of how deeply rooted the games are in Polish culture is the inclusion in the official reading list by the Ministry of Education for Polish schools. According to the Prime Minister of Poland Mateusz Morawiecki, this is the first time a video game has been included in the national educational program.

We can talk about the potential in Polish game creation, at least in terms of educational opportunities. Those interested in this field can choose from 34 majors at public universities and 26 at private universities. Almost half of them are programmer-oriented, but it’s not just IT professionals who can relate their future to gaming. It is also a workshop for artists, graphic designers, producers, and creators of plot and sound. Polish games become more popular and more complex every year, both visually and meaningfully.

The annual computer games and multimedia entertainment 一 Poznań Game Arena also promotes game development. According to the organizers, since 2004, they have gathered almost 450,000 players and fans of virtual entertainment.

The history of cinema in Poland is almost as long as the history of world cinema, and it has recognized achievements.

The development of cinematography

The communist leadership, which brought the Soviet military regime to power in Poland, began a rapid resumption of Polish cinema as a powerful means of propaganda. In 1949, the number of cinemas in Poland exceeded the pre-war level (762 against 743 cinemas in 1938), and the number of spectators almost doubled. With the formal assertion that the nationalization of the film industry would free art from commercial pressure, the film industry found itself utterly dependent on communist ideology.

After 1989, the political transformation in Poland led to the abolition of censorship and further decentralization of film production. In 1990, the Film Distribution Center was liquidated, and the former film groups began to be transformed into film studios. In fact, In the early 1990s, there was no such profession as a producer in Poland.

Attendance at cinemas has declined, with films from the United States being shown in large numbers in the country. To stem the influx of foreign films, the state changed the rules for subsidies: no more than 40% of the cost of producing the film was covered by producers, the rest was primarily financed by television, and the least – foreign countries. In 2005, the Polish Film Institute was established under the new Law on Cinematography. His task was to provide financial support for producing films of high artistic value. This decision resulted in an increase in the attendance of Polish cinema and the number of international co-productions and the spread of film education in schools. Cinema in Poland has survived the crisis. After the collapse of the communist system, retaliatory films appeared in Poland, which mainly condemned the past era of the Polish People’s Republic.

Films were made that also bypassed political topics. Krzysztof Kieslowski’s trilogy “Three Colors” (1993-1994), shot in co-production with other countries. Famous Polish composer Zbigniew Preisner worked on the music for the tapes. “Three Colors” received positive reviews, one of the parts of the trilogy “Red” was nominated for three Oscars.

The primary influence on the reconstruction of the state of Polish cinema was the success of entertainment cinema. Films such as Wladyslaw Pasikowski’s “Dogs” (1992) and Juliusz Mahulski’s “Killer” (1997) commented on the Polish reality. The latter gathered more than 2 million spectators in cinemas and has become a favorite comedy of Poles and a source of memes to this day. According to Iza Olczyk, a fan of Polish cinema, the film is “the quintessence of Polishness.” However, not comedies or even literary adaptations gained worldwide recognition. Iza admits: “Overseas careers are mostly made by films that touch on serious topics related to the tragic moments of history.” At the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, film adaptations of classic works of Polish literature appeared in Polish cinema. For example,”Mr. Thaddeus” (1999) and “Revenge” (2002) by Andrzej Wajda, “Fire and Sword” (1999) by Jerzy Hoffman or “Quo vadis” (2001) by Jerzy Kavalerowicz.

In 2002, the Pianist Roman Polyansky premiered. This is a story about the times of the German occupation of Poland during the Second World War and the persecution of Jews. The Pianist has received several awards, including the Palme d’Or for Best Picture at the Cannes Film Festival, three Oscars, and seven Caesars. And although the film was created in collaboration, Poles are proud that their compatriot directed it.

By the way, films about the unresolved issue of Polish-Jewish relations have received special recognition abroad. “In the Dark” (2011) by Agnieszka Holland and “Ida” (2013) by Pavlo Pavlikowski were nominated for an Oscar in the category of non-English language film. Ida won the first and so far the only Hollywood statuette for Poland.

As mentioned earlier, deep films about the past through the eyes of Poles are receiving rave reviews around the world. These include Andrzej Wajda’s Katyn (2007). The director has won many prestigious awards and titles: Polish and foreign. He has created several famous films, each reflecting a particular segment of Polish history and is essential for their culture and world heritage. Therefore, it is not surprising that in 2000 Weida won the honorary Oscar for outstanding achievements in cinema.

In 2018 and 2019, the world started talking about Polish cinema again. Pavlikowski’s Cold War was nominated for three Oscars at once (won the Golden Lions and 7 Eagles at home). A year later, Jan Komasa’s Corps of Christie was also shortlisted for the most prestigious award in the film industry. The film was a huge success in Poland, as evidenced by the frequency of people in the cinema – more than 1.5 million people. It is worth noting that films on religious themes are in demand in the neighboring country. They are created mainly in a negative context about the institution of the church (and they are gaining the most publicity). Still, some paintings positively show the clergy.

This year, Jan Matuszynski’s “Don’t Leave a Trace” film was chosen as the national contender for the Oscar. Again, this is a story about one of the most notorious crimes of the Polish security service. The plot is based on a real story, which Caesar Lazarevich described in a report of the same name.

1983. Grzegorz Przemyk, almost a high school graduate, was detained in central Warsaw for allegedly fighting. The boy was severely beaten in the ward. One of the policemen asked to be destroyed so that there were no traces. All internal organs repulsed Pshemika. He died. His mother, a well-known poet, Barbara Sadowska, and the opposition in her apartment made the case public. The security services want to cover up the issue by blaming the deaths of doctors or paramedics, but there is a witness, a friend of Przemyk’s, who claims otherwise.

As can be seen from the plot, Poles are still hurt by the injustice and cynicism of the communist government. After the festival in Venice, the report’s author emphasized that this is a universal story: similar events could take place in almost every communist country, the language and uniform are different.

In general, film production in Poland is now organized in the same way as in most Western European countries. Directors involve foreign investors and producers in financing their projects. Television, both public and private, provide some financial assistance. In recent years, several new production companies have emerged: Madants, Film Polska Productions, No Sugar Films, Lava Films, Aurum Films, and Opus Film, specializing in international co-production.

Since 2019, the Law on Financial Support of Audiovisual Products has been in force in Poland. He introduced a mechanism of financial incentives to produce films and series that “promote Polish or European cultural heritage.” Numerous film festivals are held in Poland, including the Polish Film Festival, New Horizons, the Krakow Film Festival, the Warsaw International Film Festival, and the annual Polish Film Award Ceremony.

The article highlights two creative industries that have emerged or transformed over the past 30 years. However, this is not the whole list. For example, Poland boasts modern interactive museums, most of which are equipped with audio guides and are accessible to people with disabilities. Here, museums, theaters, or philharmonics should be reserved in advance because people of all ages are interested in art.

At the World Press Photo exhibition in Krakow, I recently noticed how my father reads to his 5-year-old daughter next to each photo she shows and explains the context. Although the pictures there are not the most pleasant.

Or another situation:

“Mom, it’s scary!”, The child whispers at a classical music concert.

“Yes, scary and beautiful, listen quietly.”

Poles have a future in the cultural sphere.

Translated by Kateryna Chepiuk in the scope of Gwara Media’s volunteer program