Pisky-Radkivski is on the left bank of the Oskil River, near the intersection of Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Luhansk Oblasts. It’s relatively quiet here; the village is recovering from the occupation that lasted from May to September of 2022. People are starting to return. Shops are opening, and their shelves are filling up with products.

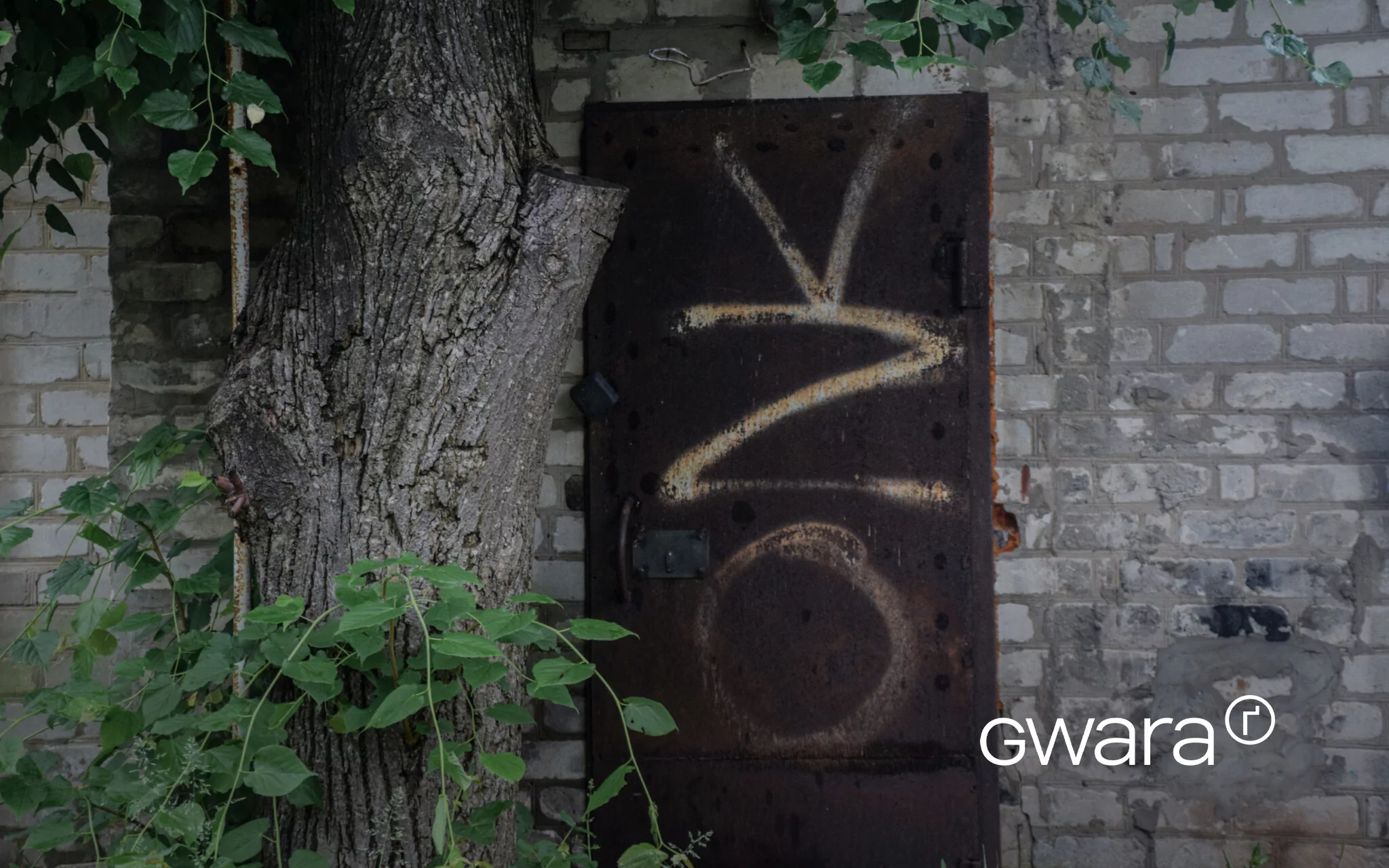

The memories of the occupation are being slowly covered with dust, but Russian soldiers left their mark on the village.

Gwara Media journalists visited Pisky-Radkivski on the anniversary of the deoccupation to document the difficulties the locals face here.

Village

May. It’s drizzling. The humid air brings the sounds of nearby battle. The Luhansk Oblast is twenty kilometers [~12 miles — ed.] away from here. Five kilometers away, the frontline.

On April 15, 2022, occupational forces entered the Pisky-Radkivski for the first time. The columns of Russian troops walked the Myru Street — or Peace Street, in translation from Ukrainian. This street is now unlike others in the village: it doesn’t have a single house that wasn’t touched by the war. Its skeletal houses stand among the thicket.

“They moved down the street and shot at the houses from armored personnel carriers,” says Victor, one of the street residents. “When this mess ended, the road was sown with shells. The next day, the infantry followed, shooting from assault rifles. When they passed the village, no shells were left — they picked everything up.”

“They moved down the street and shot at the houses from APCs. When this mess ended, the road was sown with shells.”

Victor’s family lost two houses in a few days — and their entire life along with them.

Occupation

In the first days of occupation, the family — nine people and their neighbor — was hiding in between the walls of the house.

“When troops with assault rifles finally passed by, we walked out in the yard. Looked at the street, and on the other side, another [military] column had moved closer. My daughter-in-law said, “If those start shooting, too, I’ll jump under the tank.” After that, we moved to the basement.”

The basement was in the summer kitchen [an outdoor building next to a house, where people cook and store food, traditional for Ukrainian households in small towns and villages — ed.] behind the house. Right now, it’s impossible to get in there: the kitchen entrance is filled with slates and timber.

I look out the window and see a jar, in which these people would have fermented the vegetables harvested from their own yard during summer. A box where these jars would have been kept. Both stand on the dusty table among shattered glass.

“On April 17, a column moved by,” Victor continues. “Its motor caught fire. I didn’t see the machines because we were in the basement. Russians said it’s a replaceable car with 1.5 tons of TNT inside. Apparently, ‘good riders’ overheated the motor. The explosion flattened everything around. A tank’s caterpillar thread is still on my neighbor’s roof, and a piece of another one is near my son’s house. To cover the hole [from the explosion], [they] thrown eight cars with trash, two cars with coal slag, and a car with crushed stones in there, but still couldn’t cover it entirely.”

“When we exited the basement, we saw that everything around was destroyed: the house didn’t have a roof anymore, the windows were shattered, the garage and the summer kitchen destroyed, too. Bullets and projectile marks were everywhere.

“We got out, and all we had was the sky above our heads.”

“We got out, and all we had was the sky above our heads,” Valentina, Victor’s wife, is barely holding tears. The woman can barely move her right hand and leg because of the stroke.

The family was evacuating in a hurry: shoes and personal things were thrown around the yard as evidence of their urgency. They lived with the godparents of their kids first, then moved to their nephew’s house. He is now working in the Baltic countries.

“When he’s back, we’ll have to move somewhere. We work to fix our son’s house as much as we can — we will move there when he comes back. How much more do we have to wander around other people’s homes?”

Victor’s house

We’re entering the house. A thick layer of wet dirt sticks to our shoes in seconds. The spring was rainy. Humidity peeled off the wallpapers and overgrown the ceiling with mushrooms.

“We’ve completed the renovations here literally a few months before the war.”

“We’ve completed the renovations here literally a few months before the war,” Victor looks around the hall. When he starts speaking again, he tries to hide the trembling of his voice. “My wife saw a similar design on the TV, wanted to make something similar in our place. We were doing it for us. For our kids, when we’ll die, yes, but for us to live normally as well.”

The presence of marauders is obvious in the room – all drawers are pulled out. A hunter’s safe is broken, though the key is lying on top of it. A couch is half-pulled up on the window sill. Russians have probably changed their minds and decided not to take it.

Victor says that during the first week after the occupation, Russian troops weren’t letting Myru Street residents to return to their houses. When the owners started returning, though, they saw that the occupiers had taken away motorcycles and two cars. Everything was taken from the house and the cellar. They’ve taken the fridge. They’ve shot the TV.

“Oh, cossack and the girl,” says my colleague, pointing at a dirty porcelain figurine hidden in the corner of a living room.

“He stayed, [they] haven’t taken him away.”

“Pretty.”

“[We] need to take it with us,” Victor takes the cossack statue, holding it with his shirt sleeve.

Restoration

The Armed Forces deoccupied the village on September 24, 2022. Occupation forces ran, leaving what they’d stolen behind. When the Ukrainian soldiers entered the Pisky-Radkivski, life returned here as well. But it isn’t easy to restore ruined houses and memories they’ve held. A lengthy period of rebuilding started.

“I was given three pieces of USB, 20 blocks of wood, tarps, and a handful of nails,” says Victor. “I thought I could save the ceiling after I sorted out the roof. [They] didn’t allow me to sort it out before the commission [has evaluated the destruction]. Now, the ceiling has fallen, and mushrooms grow there. No commission has come.”

eRecovery state program was launched in March 2023. At first, they allocated money for [restoration] of houses damaged due to the Russian full-scale invasion, but the homes of Victor and other Myru Street residents weren’t included in this category.

“I went to Borova. Everyone insisted I should submit an application [for home restoration] via Diia [Diia is a digital e-governance platform in Ukraine — ed.]. My wife and I have phones with buttons. To use Diia, I need to buy a smartphone. But how should I buy it if I need to pay for gas and electricity?”

Maria

We came to Pisky-Radkivski a second time in August, after the second stage of the eRecovery program, aimed to compensate Ukrainians for destroyed housing, was launched. It’s very hot under summer sunlight, so we hurry to a meeting with another Myru Street resident. We’ve found her sitting under the tree, a yard away from Victor’s family home.

Maria came to Pisky to meet us. She and her children currently live in another village. The woman lost two houses, too: her own and her brother’s.

“In the beginning, we were hiding in the corridor, behind two walls. When [Russians] destroyed [the corridor], we were in the cellar. The way we were getting into this cellar… My brother is 80 years old. I was barely able to push him through. As soon as I closed the door, boom. Then, quiet, so quiet. I got out, looked around, and the house was gone. The entire household is broken, destroyed. My brother’s house burned down first,” Maria tells us.

“As soon as I closed the door, boom. Then, quiet, so quiet. I got out, looked around, and the house was gone.”

The woman also has a button mobile phone, so she can’t submit an application to Diia. Apart from that, they don’t have documents for her brother’s house, and it’s a main requirement for receiving compensation for damages.

Maria says, “I don’t know what we can do about the documents now. They [authorities — ed.] throw us around, and I don’t have the health to walk here and there. I don’t know if I should bother. People tell me I’m wasting my last health.”

Maria is bewildered at how she solved the issues related to private property without documents in the past, but they were a must now. The woman wonders if [demanding documents — ed.] really makes life easier.

Jemma

We decided on a time we’d meet to get Maria home and went to look for our last hero. The connection wasn’t good, and we couldn’t reach Jemma. Suddenly, a man on a bike outran us.

“Are you reporters?”

It occurs that this is Jemma’s husband, Serhii. From Myru Street, we turn onto a dirt road. A house is revealed from the greenery, greeting us with a dog’s barking.

“The villages in the Sviatohirskyi district [a district in Donetsk oblast, — ed.] are completely destroyed. Everything’s ruined. Here, we’re more or less fine,” says Serhii, who returned from Kramatorsk recently, while Jemma is brewing coffee for us. Stepan, the dog, is circling around our feet. A TV program about aliens is running in the background.

Serhii and Jemma were born in Kramatorsk but lived in Pisky for a few dozen years. Their relatives in the Donetsk region offered them [a place] to evacuate [to], but the family didn’t want to leave their pets.

“We had three dogs. Their hearts probably couldn’t stand the bombardment, so they died. And so many leave pets who served them for so many years behind! Can’t stand them,” Jemma notes.

Currently, the family has two dogs, Stepan and Varvara, and a few cats.

“We have a cellar in the shed. We were hiding there,” Jemma recalls. “We’re getting out, and the house is gone – destroyed. We thought, well, we’ll live in the shed next to our cow. When we heard the second and third missiles hit, we sat in the cellar and caught a scent of smoke. The neighbor cried, desperate, “Your shed is burning!” Ah, the way we’ve jumped out of there.”

Then they saw that the house’s roof had been blown off and the windows shattered. Inside, everything remained more or less intact. The debris damaged the TV and some furniture. The couple went to live in the house of their deceased son. They transported all their belongings on a wheelbarrow. “We tried to be visible for the occupiers. You’ve seen the bushes we’re living in.”

“I still have tremors in my hands; it was scary to live through this.”

“We were so afraid of sleeping at night that we slept in a cellar [for a month during the occupation — ed.] We were scared that someone might get inside to hide and [Russians] would be shooting at everyone. As soon as there were missile attacks, we dropped everything and ran to the cellar. I still have tremors in my hands; it was scary to live through this,” Jemma says.

“We think our house was bombed because our grandson serves in the AFU. We didn’t hide it. We had to burn his documents in case [they’ll be searching us], though. Also, in our grandson’s room, instead of a carpet on the wall, was a blue and yellow [Ukrainian flag]. After we moved, we had to hide it. Otherwise, the trouble would have found us.”

After our conversation, we ask Jemma to show us her damaged backyard. We inquire about eRecovery during the walk, and, to our surprise, the woman has already applied by herself.

“Of course, I am on Facebook,” the woman says as she demonstrates her smartphone.

In the center of the village, that’s become much livelier since our last visit, we meet with a village’s starosta, a young man with a tired face. He got the post accidentally. He thought he would quickly change the village for the better but faced limited resources, bureaucracy, and a lack of support from the higher-ups.

We ask him to explain how to submit the eRecovery application to Maria.

People often don’t know about existing support programs in deoccupied villages this far from the large cities. Not everyone, like Jemma, has the opportunity and skills to figure out their way with digital systems.

In Pisky-Radkivski, specialists in the village council help people to submit applications.

“We’re helping download Diia and Privat24 [an app for a PrivatBank, Ukrainian national bank — ed.]. We only ask people to bring their documents and photos. Because it’s mainly senior people [who come here for help — ed.] Also, we create inspection reports for the damaged housing,” says Olena, a file clerk.

As of the beginning of September, the village residents filed 81 applications for financial compensation for damaged or destroyed property, Borova’s village council said. However, the residents of Myru Street couldn’t receive the compensation at the time of writing this article because commissions inspecting the buildings didn’t give them the necessary permits.

Authorities promise that local centers providing administrative services where people could apply directly for eRecovery will be open until the end of the year.

Author: Polina Kulish

Editor’s note: This story is a piece of our reporting from the autumn of 2023: you can read it in original Ukrainian here. We’re translating it to document, show, and raise awareness among English-speaking audiences about the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian occupation, and the struggles people in Kharkiv and the Kharkiv region faced and are still facing.