Living with artificial light deep underground is no longer a film plot, but our reality.

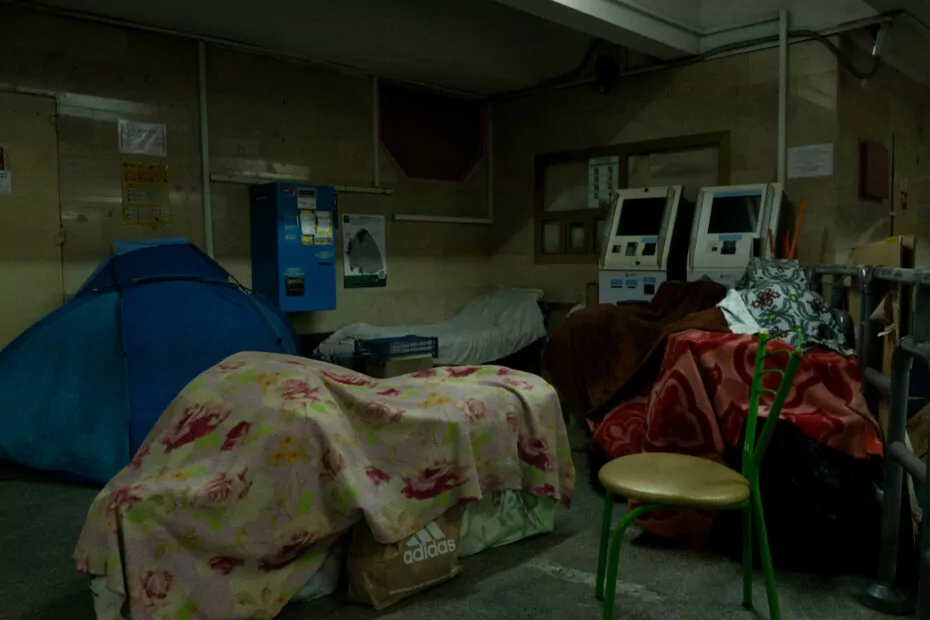

Kharkiv metro station “23 Serpnia”: tents, mattresses, the noise of the subway, and a constant stream of people. They have been here since February 24. The reason is the fear of shelling.

Gwara Media journalists talked to the displaced residents of the subway to show their stories.

Leonida Honcharova, 73 y.o.

Leonida got to Kharkiv in September. She was being taken out of Kupiansk during another shelling.

“It was September 22, I lived in Kupiansk with my granddaughter and two great-grandchildren. In the morning, I decided to go to the town center to get humanitarian aid. Then the heavy bombing started. I was scared and started crying. Police officers were standing nearby and offered to take a bus to Kharkiv.”

Without her belongings, only with the bag she was going for humanitarian aid, Leonida got into the car and was taken to the regional center to dormitory No. 11.

“I had a good neighbor, but she soon left to visit her daughter in Kyiv. Then another woman was moved in, and we couldn’t get along with her,” says the granny. After that, she turned to a senior employee of the dormitory with a request to move to one more housing.

The manager was very aggressive towards her, but she did relocate her to another place. Then the problems began: the head of the dormitory began to persuade Leonida to relocate to a boarding house, but she refused because the only thing she wanted was to return to her home.

The story about the dormitories is quite long – the old lady changed shelters three times, and there were attempts to put her in a boarding house. Volunteers came to visit her, but no one offered to check on her home.

“While the manager was calling for volunteers, I was reading a book and fell asleep. I was woken up by two men and a woman. One of them grabbed my hands and said we were going to a boarding house. They searched me and demanded my passport. It was good that I hid it in a safe place. The volunteer got into my bag, and there was money in it – all my savings, and she took it with her,” Leonida adds, “They let me take a torch and a towel, and then took me out of the room. So many people were there, and I was alone.”

At the boarding house, the head doctor did not admit her because she refused to show her passport and sign documents. She had to return to the dormitory. The volunteer returned the purse, but without the money.

The old lady went to the manager, saying that her money was missing. After that, the woman came with another volunteer who again persuaded her to go to the boarding house. But Leonida refused, which made the dormitory manager very angry. On one December evening, she was evicted from the dormitory.

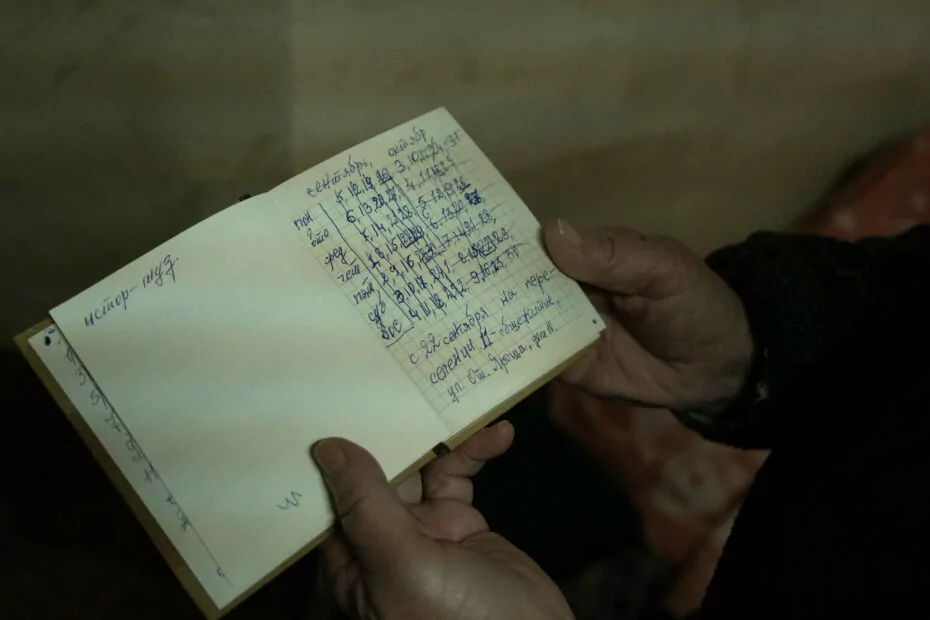

“I didn’t know what to do, because the city was a new place for me. I wanted to freeze to death. I lay down on the street and stayed there. Then the dormitory staff took me to the subway, but to the “Botanichnyy Sad” station. There they warmed me up, gave me a drink, and let me spend the night. The next day, on December 3, I was sent to 23 Serpnia” metro station”, Leonida takes out a notebook with all the dates.

She has been living in the subway for 2 months now: “I feel good here, no one offends me. We all help each other. At that time, living in a dormitory was very expensive. Although there is no heat and other amenities here, it’s easier mentally.”

When asked if the house is still intact and where her granddaughter is, the grandmother says she doesn’t know anything. The last time she saw her house was in September.

“When they were taking it away, the house was intact. People who came here later told me that terrible things were happening in Kupiansk. I am very worried about my granddaughter and great-grandchildren.”

Leonida does not know where her family is now. She says she will live here until spring, and then she will try to return home.

Two women sit a little further away from Leonida. These are Natalia and Liubov, they are from Kharkiv.

Natalia Shakhova, 59 y.o.

Natalia has been in the underground since the first days of the war. She used to work in a kindergarten, but it is now closed. The woman’s relatives are in Poltava, so she is left alone here.

“I actually live in Kharkiv, I have an intact house, I go there, but I’m afraid to spend the night there. I remember the first time I heard explosions and sirens and didn’t immediately understand what was happening, so I went to work as usual. A girl came out and said to me: “Didn’t you realize what happened?” I understood that the war had begun only after the explosion next door. That’s when I came here.”

She goes home almost every day to cook, wash and do her housework.

“I will stay in the subway as long as there is martial law. I don’t want to leave Kharkiv because my roots are here. I was born here, and I will stay here. Furthermore, I have the necessities – that’s enough.”

Liubov Guchenko, 72 y.o.

Liubov, like Natalia, is from Kharkiv and came here in the first days of the war. The woman got hit by an air strike and decided not to waste time and go to a safer place.

“I remember being hit by an air strike in Kharkiv and a young man covering me with his body. That’s how I ended up here. This is my second home.”

The windows in the flat are smashed, and instead of glass, they are covered with plywood. Her daughter and granddaughter went to Germany, and she stayed with her matchmaker and son-in-law.

“They wanted to take me with them (her daughter and granddaughter – ed.), but I lost the opportunity because I didn’t respond to the call in time, so they left without me. Now they criticize me.”

Sometimes Liubov visits her home, but she returns to the subway at night.

“I am very scared. When there were explosions, I was hiding in the basement. The house was shaking, the windows were blown out everywhere, it was cold, water was leaking, and you could hear the siren all the time, but here I feel safe,” she says.

She is in constant contact with her relatives, adding that her granddaughter calls and asks her to return home, but as for Liubov there’s no safer place than this metro station.

“If somebody kick me out of here, I’ll go back home, of course, but I don’t really want to, because it’s scary there.”

Yevheniia Ivanova, 42 y.o.

Yevheniia has been in the subway since April 29, after the de-occupation of Ruska Lozova village.

“My nephew lives next to this metro station. When he found out that we were liberated and came to the city, he immediately called us and directed us here. He said we would be welcomed here.”

Her family’s house in the village was badly damaged: the roof, windows, and ceiling collapsed – everything was black.

“Every time I go there, it’s scary to see it, but we are slowly trying to restore the house. First, we filed a report with the police about the damage to the property. Secondly, the gas supply has been restored in our village, but our neighbors next door had their house completely destroyed, and because of this, our pipe was cut off. We had to wait for three more weeks for repairmen to fix it.”

It was difficult to stay there without electricity because everything was powered by electricity.

In Kharkiv, the family was provided with a two-room flat near the underground, but the woman can only stay there during the day, returning to the shelter at night.

Sadly, the dream never ended, and now Yevhenia and her 17-year-old daughter spend the night in the subway. Her husband and mother have already adapted and stay in the flat.

The woman explains that when they were asked to leave the subway in May, she had to live at home for two weeks. But it was tough – I hardly slept, I was very nervous. Then the shelling of the city started again and Yevheniia returned to “23 Serpnia” station.

Currently, she is slowly starting to get out of the underground and get used to the new reality.

“I think that most people stayed here because of the psychological trauma they suffered as a result of the war. Those who were really afraid to return home gathered here. We had psychologists from Doctors Without Borders come here, but I personally did not feel any better. I just need time to adapt. I’ve got used to the subway, although at first I heard a lot of unpleasant comments like “Why are you sitting here, the war is over?”.”

She considers the metro to be the safest place at the moment, but she hopes that a good bomb shelter would be built in the village where she lives to shelter in. She is also thinking of arranging her own basement.

Yulia Mykhailenko, coordinator of the group of people living at the metro station since May 22

A woman also stays overnight here. She has been here since the beginning of the war, when almost 2,000 people hid in this place.

Yulia said she became a coordinator on May 22:

“At first, I just helped with food distribution. When I got out of the wagon on the third day, a guy came up to me and asked if I had a knife, and I said yes. He took me with him to the service unit. There was food there. People and the military were taking everything from the markets, because they did not understand how long it would last, and looting could prosper. We were cutting it all up and dividing it among everyone who was here.

There were many different volunteers, and later people left, but the food remained. And every morning I continued to divide everything we had. First for 1300 people, then for 1000, and then for 800.”

When everyone began to leave, she began to order food herself and take photo reports for World Central Kitchen, which was helping at the time. Afterward, WCF focused on the de-occupied territories.

Then, after May 22, when everyone was asked to leave the subway, not many people stayed there. Residents returned to the shelter after the shelling on May 26. By the fall, about 120 people lived there.

That’s when Yulia started struggling for the rights of those who stayed in the subway:

“I started fighting right away, it’s unlawful. I called the police, because it is illegal to expel people from a shelter during martial law. The subway is a shelter. This is how we live today. For many people, it is mentally difficult. We try to help the metro workers. For example, we clean the area ourselves.”

Text by Daria Lobanok.

Translated and edited by Denys Glushko.