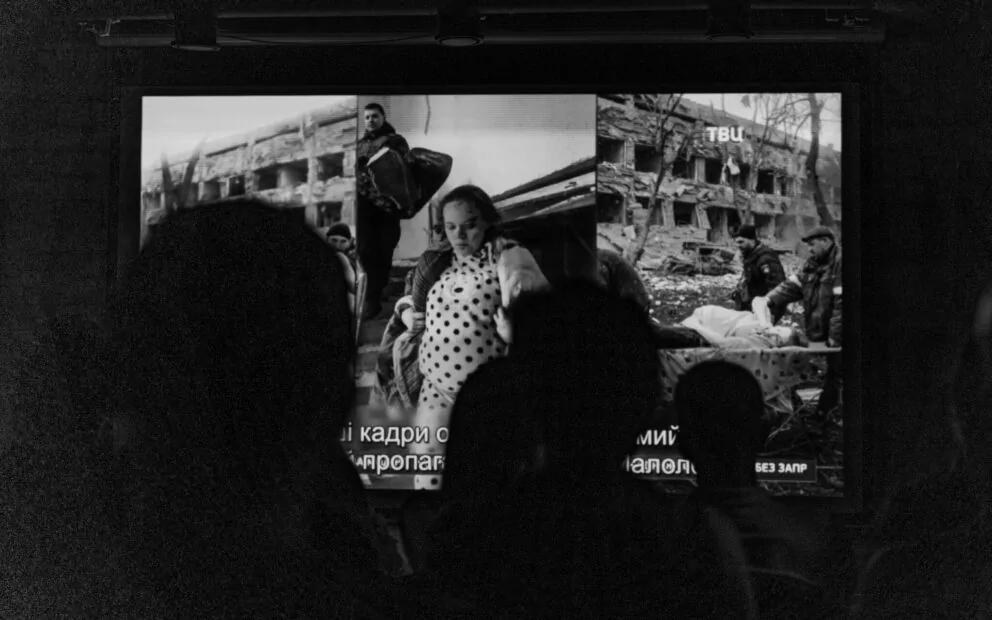

The film 20 Days in Mariupol premiered in Kharkiv on August 31. The movie is about the beginning of the Russian full-scale invasion: the bombing of residential buildings, constant shelling, deaths of Mariupol residents, and mass graves. After watching the movie, people could ask Mstyslav Chernov, the director, questions.

At the beginning of the Russian full-scale invasion, a team of Ukrainian journalists from the Associated Press were stranded in the besieged Mariupol. As the only international reporters remaining in the city, they documented the lives of Mariupol citizens during the war. The film is based on Chernov’s everyday news reports and personal footage.

“I am happy to finally show this film in Kharkiv, my home city. I think you understand that when I show this movie to international audiences, I need to explain: everything you’ve seen in the movie is everyday reality in Ukraine.”

You’ve spent 20 days in Mariupol. When I watched the movie, I thought that when a subtitle with a day shows up, you start counting the days until leaving the city. What was your feeling of time under the siege?

[It all felt like] one day. You almost don’t sleep, so you don’t feel that one day ended and the second or third began. Even the “20” in the movie title appeared after we left the city. I started to write an article, 20 Days in Mariupol, that became the foundation for the film, and counted the days using original video files. They told me how much time had passed. But when you’re lying on the floor with hospital patients; when no one is sleeping because they don’t have painkillers; everybody’s groaning; when there’s a terrible smell – and that sticky fear hangs in the air because there’s constant shelling – time stops.

What happened to the heroes of your film?

The guys who helped us get out are from the Special Operation Forces of the AFU. Some of them were able to leave Mariupol, some stayed. Some were killed, others were captured. Right now, everybody who was in captivity has already returned to the frontline. We’ve shown them this film. They watched half of it and said, “No, let’s finish watching tomorrow.” That happened several times.

How have you been recovering after leaving Mariupol?

When I was working on this film, it got easier because I could ask questions that had been bothering me. I remember that the day after we left Mariupol, [Russians] bombed the drama theater. We were so shocked because we knew how many people were there. No one knew anything because there were no journalists in the town anymore. At once, we started an investigation – and figured out that around 500 people had died [in the strike].

“After that, I went to Bucha. Then, I called my editor and said, “I need to go to Kharkiv.” Here, the downtown was shelled constantly before the [Ukrainian] counteroffensive. I felt that I needed to be close to home.”

Then, we started editing the movie. During the day, I woke up at four in the morning and filmed rockets hitting Kharkiv – or went to the frontline. In the evening, we worked online with a video editor from Boston – worked on 20 Days in Mariupol. [I was in] a terrible state: first Kharkiv being shelled, then editing. But eventually, it allowed me, to, again, ask questions and understand what happened [in Mariupol], realize the scale of things that happened. And we had a goal. This is a key to survival: having [a goal, a point] towards which you move.

Do you talk to your team – Eugeniy and Vasylisa – about what you’ve been through?

Honestly, no. Reflection is for later. We all feel that if we stop, it’ll be incredibly difficult to start moving again. It doesn’t mean that reflection and psychological rehabilitation aren’t important. For soldiers, for journalists, and for other people, they are important.

Would we be able to watch what you’ve filmed in Kharkiv?

You can look at [the footage] on my Instagram and Facebook, but the sheer volume of the materials [filmed] requires a lot of work. I hope something from Kharkiv will be included in my next project.

How did the foreign audience react to 20 Days in Mariupol?

We had many conversations about the form [of the film]. Discussed what and [and how much of what has happened] is okay to show to the audience. We feared we’d push them away. But that didn’t happen. We have been looking for a balance for a long time: literally, every centimeter of every shot where people are dying or wounded was thought through; every second was reviewed to treat the victims respectfully.

“Before the movie was released, I was told, “Mstyslav, the movie is too heavy. It should probably be released just on our channel.” And I said, “Let’s try to submit the movie to at least one festival.” Eventually, the movie did get into the Sundance festival and got an award. The viewers wanted to watch and understand.”

The reaction to the movie changes from country to country. They usually have two questions, “How to help?” and “When will you show this to Russians?” Such attention to the movie proves that big documentaries are needed right now. Because after we watch a minute or two of the news, we simply get on with our day. We don’t realize the scale, the intensity of the tragedy through the short forms, but with long projects, we can get deep into the story.

How can we fight Russian propaganda? Because it’s everywhere – many propagandists in Europe and America, too.

We need to document absolutely everything, even things that seem unimportant. I understood that when I edited footage from Mariupol. They played their role. So the first thing we can do is to record and save everything – [we have] so much information [that] it can be lost later. It will be hard to find and to process, but it will be necessary to do [so]. But here’s the problem: When we fight propaganda, we’re lowering ourselves to its level. Fighting it, in this case, isn’t always valuable. We’re lucky that justice is on our side.

“Documenting everything that happens will be enough in the beginning, and then we’ll need documentary projects because, sooner or later, we will see the interest in Ukraine declining. I film conflicts for nine years and understand it’s normal. If nothing new will happen, if the frontline won’t be moving, then Ukraine – won’t disappear from the press entirely, of course, – but will fade to the background.”

When the festival cycle and the cinema showing are over, the documentary will be released on YouTube. It was one of the conditions of collaboration with the EU. You can watch the film at the end of October or a bit later.

On August 24, STB released a war drama, “Yuryk,” about the boy who escaped Mariupol. What are your impressions of this movie, considering you were in the city at the beginning of a full-scale invasion?

I didn’t like it. But I think it’s already necessary to try to shoot feature films about the Russian-Ukrainian war. If we don’t do that, especially in the case of Mariupol, this vacuum will be filled by propaganda. The international perspective is important for work like this, and we need to find the right tone for fiction. If we lose it, there will be no realism, no relevancy, and the movies will offend someone.

You shoot 30 hours of material and release a movie for an hour and a half. What shots were the most difficult to remove?

I wanted to add a lot into this movie. Talk more about children who died, about the work of the Ukrainian Red Cross – we worked with them for a long time until the building they were staying in was bombed. Sadly, some scenes from the Mariupol hospital aren’t shown in the movie. We didn’t have enough batteries or memory cards. Some moments weren’t recorded because I was hiding somewhere and forgot to press “play.” Some things were important, but repeating them didn’t make sense: they interfered with the story.

Do you know how the material must be filmed so it [can be used] as evidence?

An essential rule for the material is that files must be original, ideally with the location data [sewn into the file], but it isn’t always possible. The issue is that photos and videos aren’t enough to conduct an investigation; [investigation needs] witnesses and experts, satellite shots.

While Mariupol remains in occupation, chances for justice are lowering. Bucha was a unique case in that sense because of the quick de-occupation: the bodies have still been on the crime scenes, which allowed to start the investigation quickly. In the case of Mariupol, with the scale of the crimes ten times higher than in Bucha, the chances to document all the horrors are, sadly, not high.

How often did you feel despair? Not fear, but an acute feeling that this can be the end of everything?

The fear was constant, and it was impossible to get used to it. But it’s necessary to overcome yourself when the new day is starting. You have to get out and keep filming. Everybody’s working around you: doctors are running [back and forth], someone brings food, carries the wounded, surgeons and nurses perform surgeries, soldiers, police, and volunteers drive around the city despite the constant shelling. And you understand that you have to keep working, so no, I didn’t despair.

“Even in the worst moments in the movie, someone always supported those who suffered. There was no despair; the hope always remained.”

The documentary 20 Days in Mariupol got several Ukrainian and international awards.

- Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival (2023);

- “F:ACT” award at the CPH:DOX film festival (2023) (nomination);

- Greg Gund Memorial Award (2023);

- Cinema for Peace Award (2023);

- The main prize in the DOCU/UKRAINE competition and the Audience Award of the Docudays festival (2023).

Vika Mankovska