The names of some people Gwara talked to in this article are changed because of the threat of Russian reoccupation of the left bank of Oskil.

KIVSHARIVKA, KUPIANSK-VYZLOVYI, UKRAINE — “The water will get in.” Volodymyr circles his car with an attached trailer. He doesn’t think his “Volga” will survive the upcoming Oskil crossing.

“The water there reaches up to about your knees,” one of the volunteers tries, aiming to soothe, but Volodymyr only sighs, mournful.

“Don’t you have door seals?” another volunteers says, opening the back door to the car. Two cats, black and white, are bundled up in the bag there, also ready to leave. “Yes, you do. Everything’s fine.”

Volodymyr doesn’t look convinced. But then, his family—his wife Natalia and her father Serhii—does not have muchchoice. To leave Kivsharivka more or less safely, they must go through the crossing. The other path is increasingly targeted by Russian troops as Moscow tries to take, again, the part of the Kharkiv region to the east of the Oskil River.

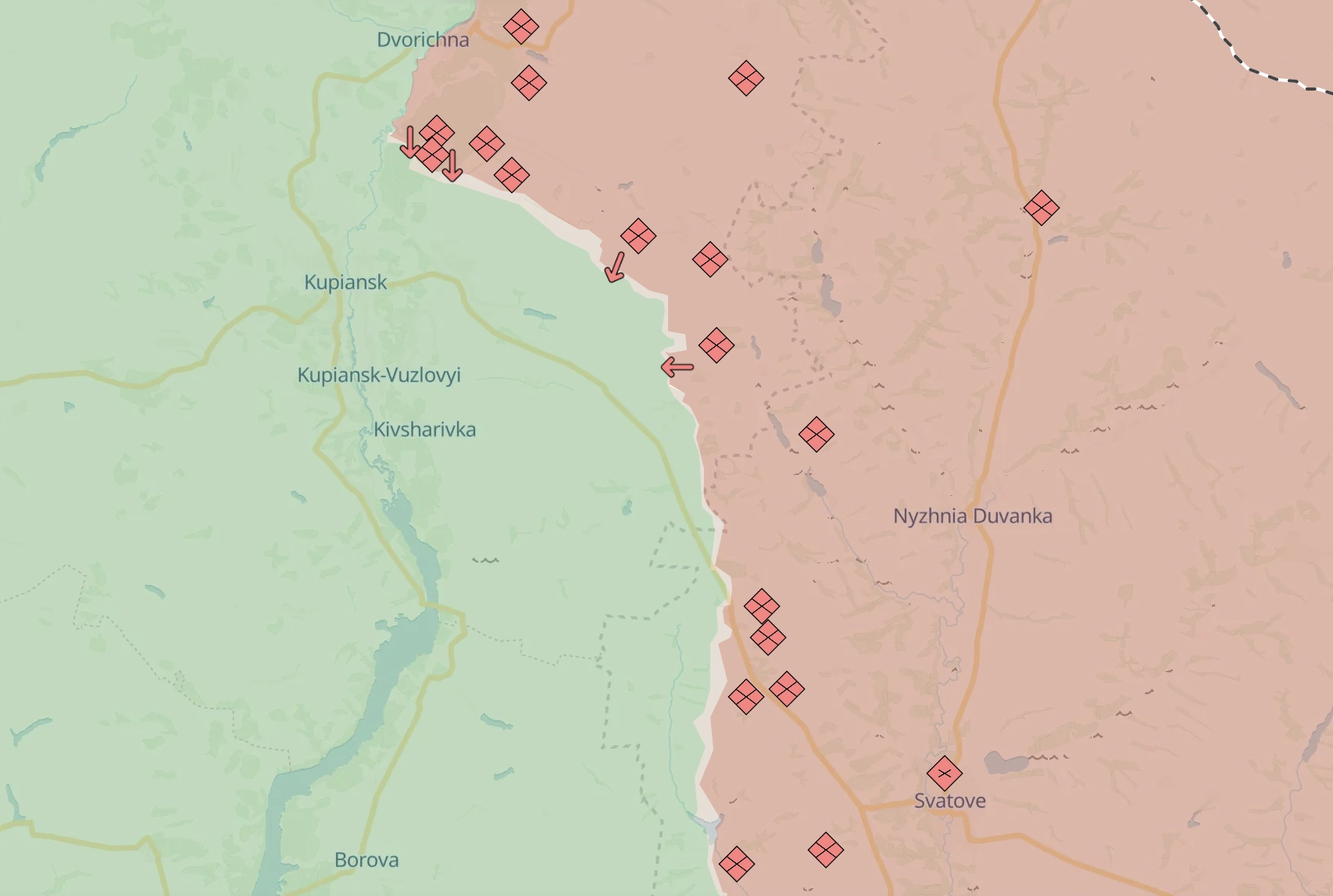

Ukraine’s Kharkiv counteroffensive pushed Russian troops out of most of the Kharkiv region in the autumn of 2022, and since then, they’ve been chipping away at the Armed Forces’ defenses, trying to occupy the territory they were pushed from again. Located about 70 miles from Kharkiv, Kupiansk is an important logistics and railroad hub for the entire region and was most useful to Moscow’s supply lines in the first months of full-scale invasion. That’s one of Russia’s main targets.

Over the year, prodding for weaknesses in Ukraine’s defense with countless mobile groups and utilizing the advantage in firepower, by December 2024, Russia managed to get close to the river in two large sections northeast and southeast of Kupiansk. The military says Moscow’s overall plan for the region is to seize the entire left bank of Oskil.

Local authorities announced evacuation from the Kupiansk district to the east of the Oskil River back in the spring of 2024—and, during autumn, leaving became mandatory, first for families with children, then—for everyone.

Back in October, Gwara Media joined volunteers from “Nezlamna” (“Unbreakable”) charity on an evacuation mission to the left bank of the Oskil River and talked to people deciding to leave or stay amidst frequent Russian attacks.

“Each time you go, it’s like the last time.”

After more than 2,5 years of going to the places Russia approaches to get people out of them, they make the entire thing look easy. Joke as they wait for their colleagues near the gas station, tease each other, tell the stories from previous evacuation missions.

“We’re always late because some bastard is sleeping too long,” Slava Ilchenko, a volunteer who just arrived at the gathering, says. His dog, Dezi, whirls around his legs in an excited blur. She’s one of Slava’s rescues from multiple evacuations—he couldn’t part with her after she jumped right onto his car’s passenger seat and refused to leave.

“No one’s overslept today…” Oleksandr Pidhirnyy, another volunteer, laughs. “Why insult yourself? Okay, okay, let’s move.”

“Nezlamna” team disperses to their cars, and their cars move through the smoke from forests, burning because of Russian airstrikes at the Kharkiv region. The smoke is so thick, one can barely see the road.

Airstrikes are not the only danger volunteers have to account for. “Yesterday, several senior women agreed to evacuate from Kruhliakivka. We were driving to them and saw the petal mines thrown on the road by Russia. And at the end of the road, there was barbed wire and TMs [ТМ-62M — Soviet anti-tank mines — ed.],” Slava says.

Remote mining allows Russia to target civilians and prevent evacuation where their troops can’t reach. That significantly complicates getting from the left bank of Oskil to safety. That day, the “Nezlamna” team couldn’t reach the women.

Volunteers are especially cautious of drones. Russia deliberately drops explosives from FPV drones on evacuation missions: in October, they killed a Kharkiv volunteer from “Rose on Hand” during the evacuation from Donetsk Oblast; in November, struck near one who was fed abandoned animals in Vovchansk; in December, targeted evacuation bus, injuring two people, also in Donetsk Oblast.

“It’s gotten harder to evacuate people. Each time you go, it’s like the last time. FPVs and other drones are constantly flying above our heads. But if not us, who’s going to help people to evacuate?” Oleksandr says.

Russia also tracks volunteers’ accounts online. The team says social media is a valuable tool to reach people who need help and establish trust, but these tools can also be exploited. Less than an hour after the team crosses the river and records a video report for their social media, Slava finds that video on pro-Russian Telegram channels, murmuring, “Oh, I’m fucked.”

Not wanting to go

Today, the team will get people from Kivsharivka, Kupiansk-Vyzlovyi, and Kurylivka to Kharkiv, to the Coordination Center, an organization that curates evacuation and humanitarian aid in the region. There, people will be given life essentials—food, hygiene products, clothes if they need any—and either assigned to a dormitory or provided with money for the tickets to the cities they’ve chosen to go to.

Not everyone wants to leave, even despite the danger, palpable here on the left bank.

Maria sells vegetables at the desolate farmer’s market in Kivsharivka. Her colleagues scatter around from journalists but remain close, their murmurs, outraged, quiet in the background. People in places Russia targets often aren’t fond of being filmed, afraid Russia will target the places they frequent or that their appearance in Ukrainian media will get them in trouble if Russia takes over their homes.

There is a sound of shelling in the background. Maria points to the side, where a Russian air strike destroyed a small shop to its foundations, killing Maria’s acquaintances, colleagues. “The girls working there died in this attack,” Maria says, her voice cracked. “One of them burned alive there. A shop’s stocker burned, too.”

Maria would leave if she was sure she and her husband would find work and proper housing in the next place. They used to be chefs, taking seasonal jobs to Odesa and Carpathians to cook for local restaurants. Now, she’s not sure if they’d find work in Kharkiv, and what she knows of accommodations Ukraine provides for internally displaced people (IDPs) also doesn’t encourage her to leave. Her friend from now-occupied Rubizhne, Luhansk Oblast, who evacuated to the city, is her source on the latter. “She says there are 15 people in the room, says there is no bomb shelter, cries every day,” Maria says.

Despite her doubts, Maria tries to convince her husband to evacuate, but he isn’t budging. “Everyday, I try to, until we’re almost fighting,” she says, trying to hold back tears. The couple have already lived through one Russian occupation.

Bell peppers, tomatoes, eggplants and other vegetables are presented on Maria’s stall, ripe and bright, though Maria says the harvest wasn’t good this year. “We didn’t have rain. It was hot. Then, we didn’t have electricity and water, couldn’t use the pump to water the garden.”

“We’ve never thought our senior years would be like that. You want to die just to rest,” Maria says.

Volunteers say the fact people don’t want to evacuate early is one of the biggest obstacles to their work. Oleksandr explains, “Today, they don’t want to leave, but when Russia starts shooting, destroying houses, they panic, call us, and want to go.” Sometimes, like when Russians mined the road to Kruhliakivka remotely, it’s too late to get them by then.

Another difficulty, Slava says, is that both Russia and local opportunists disrupt evacuation via misinformation, fraud—or via providing paid services. Volunteers of “Nezlamna” often have to convince people evacuation is free, that people leaving the left bank will not be abandoned on the outskirts of Kharkiv. Such rumors circulate all around communities Russia endangers.

“Locals aren’t giving us [their] phone number. But we know that they charge 5,000 hryvnias for evacuation, want plus 1,000 [for travel] with a bag, another 500 [if you go] with a dog. So-called volunteers. We can’t catch them. That business is flourishing,” Slava says.

Before Maria from the farmer’s market shares her struggles, she asks about Kharkiv. Says, “Kharkiv also suffers. Makesone think, where to evacuate.”

Nothing is safe

Alla, a woman evacuating from Kupiansk-Vuzlovyi along with her grandma, says that she plans to go to a city in the west of Ukraine after Kharkiv. “I’ll go to Rivne… My kids live there. I’ll get my grandma to Rivne. Because it’s scary here, and it’s scary in Kharkiv.”

The danger here, though, is much more frequent than in Kharkiv. Oleksandr, 70, plans to evacuate a few days later along with his dog, Zhuk [“Bug” in translation from Ukrainian].

In February 2023, Russian shelling injured Oleksandr in the shoulder—he says he couldn’t sit, couldn’t lay down because of the pain. Two weeks before he conversed with Gwara Media, another Russian attack destroyed his country house in Novoosynove—he’s been living there since his wife died. Oleksandr has recovered from last year’s injury, but his house won’t. He says that after the Russian attack, everything there burned down.

“They destroyed everything I built, everything I have been building for 40 years. That is nothing now. Everything’s gone.”

His dog also has been touched by the war. He survived two Russian strikes: the recent on Oleksandr’s house and the one on Oleksandr’s mother-in-law, Nadiia’s, home in Berestove, a Russian-occupied settlement in Kharkiv region northeast of Kivsharivka. After her house was hit, “she abandoned her goats, ducks, chickens, took the dog and walked for 10 kilometers to safety, away from the airstrikes.”

Now she lives in Kharkiv, in one of the dorms for IDPs—receives pensions and works to earn a little extra money. “Maybe I’ll live with her for a bit, too. A bit with her, a bit — with my grandson,” Oleksandr says. His grandson also lives in Kharkiv.

Danger changed a lot, too. Oksana, who lives on the outskirts of Kupiansk-Vyzlovyi and also can’t convince her husband to evacuate (“He says he’ll die of boredom there,” she shares, tone mischievous), says:

“In the past, [Russian] missiles just destroyed things. Now, everything burns. Who knows what they are throwing at us, the thing that burns everything down. It breaks houses in half. It wasn’t like that before. And now, this smoke… The forest is burning. We woke up today, and everything was grey. You could see no village, no home,” Oksana says.

One of the reasons everything burns might be Russian glide bombs. They started using them often last year in the east of Ukraine. Glide bombs, cheap and highly destructive, played a significant role in the occupation of Avdiivka, in Russia’s attack on the north of the Kharkiv region, and the ground they’ve taken since in Donetsk Oblast. There’s no way for Ukraine’s air defense to shoot them down except for targeting the aircraft from which they are launched with allies-provided weapons.

Oksana realizes that, with Moscow’s troops advance, things will get worse on the left bank of Oskil—but she can’t abandon her husband. Before saying goodbye, she shares another reason that keeps him here.

“We had… two houses. They belonged to our parents and my husband’s sister. A Russian bomb fell between them. [His] brother, who lived in the parents’ house, was killed, and the sister and her husband left to live with their daughter in Kharkiv. So my husband goes there everyday, watches over these destroyed two houses. That’s all he’s doing.”

“It’s good that you’re still coming here,” Oksana says to volunteers. “I always tell my husband—if they stop coming, what we’re going to do, swim the Oskil River?”

Back through the river

Natalia, Volodymyr’s wife, chats with her neighbors while her husband anxiously paces near their Volga and coos to their cats, says they wouldn’t decide to leave if it weren’t for the fear of being forgotten.

When Ukraine liberated the Kharkiv Oblast in 2022, she says, “I was terribly afraid that they’ll abandon [the left bank] and won’t liberate us. And here I am again, afraid that Russia will torture [this place] to death, and we’ll have Vovchansk here.”

Vovchansk, a city that was one of the targets of the Russian ground offensive in May, was almost completely destroyed, first by Russian troops’ bombing their way forward with the glide bombs, then by urban combat. Back then, residents of many northern settlements of the region, like Natalia, were leaving their homes for the first time, not wanting to go through the possible Russian occupation again.

For the second time today, cars of the volunteer team go into the waters of Oskil. Volodymyr and Natalia’s car with an attached trailer follows. Ludo Gualano, an Italian volunteer who came to Ukraine to help people affected by Russia’s war, watches their: first the wheels on “Volga,” then the trailer’s wheels.

Volodymyr and Natalia drive, without an issue, to the right bank of Oskil. The water doesn’t get into the car. When they reach the other side of the river, Ludo smiles and lets out—barely noticeable—breath of relief.

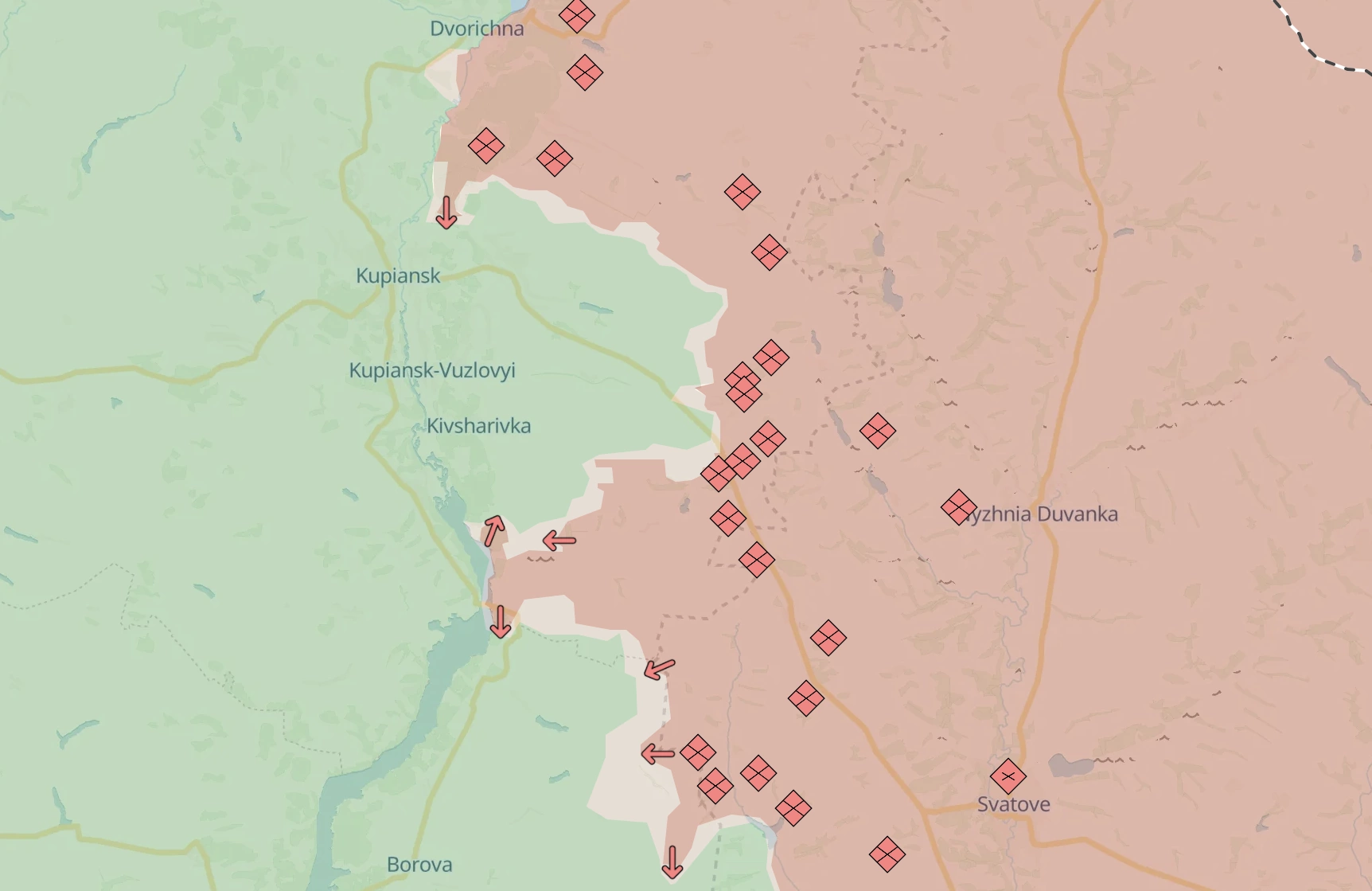

At the end of November, almost two months after this expedition, Slava Ilchenko still goes over to the left bank to evacuate people. The Oskil crossing the team used in October is now closed for civilians and volunteers, so Slava joinsUkrainian soldiers in their ventures to the left side. For evacuation missions, it’s the only way to get there—and to get people and abandoned animals—to safety.

Russian troops try to attack the crossing from two flanks, but Ukraine has been repelling them so far. Against the backdrop of Russia gaining more territory in Donetsk Oblast in the last months, they sent one of their best brigades to push the Armed Forces beyond the river. If they succeed, Ukraine will have to use Oskil as a natural line of defense—and counterattacks across the river, as Ukraine’s learned from both the Kharkiv counteroffensive and Kherson liberation, will be incredibly complex.

On November 28, Andrii Kanashevich, the head of the military administration of the Kupiansk district, said that the pace of evacuation from Oskil’s left bank had dropped.

“There are no conditions for a full life on the left bank, and it’s impossible to restore them because of the safety considerations. And staying through winter without electricity, gas, and water is not very comfortable.”

Kanashevich said 1830 people—and no children—currently live on the left bank in three communities of Kharkiv Oblast, threatened by Russian advance there.

Hi, my name’s Yana Sliemzina, and I wrote this field report for you to catch a glimpse of what Ukrainian civilians living close to the frontline go through amidst Russia’s war. Thank you for reading it, that’s an immense support. If you want to support our Kharkiv-based newsroom more, subscribe to our Patreon or BMC, or donate to us via PayPal. Thank you!

Denys Klymenko, former reporter and videographer for Gwara Media, contributed to the article.

Cover photo: Oskil River in Kharkiv region, October 2024 / Yana Sliemzina, Gwara Media