UKRAINE, KHARKIV, May 6 — For the fourth time, classical music sounded for Kharkiv residents against Russian attacks. On May 2, the Kharkiv Music Fest took place at the “loft stage” of the Kharkiv National Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre, one of the safe places for art in the city located just 19 miles south from the Russian border.

“Kharkiv Music Fest existed for eight years, but we made just three normal events over all this time. It’s my personal tragedy,” said Serhii Polituchyi, the president of the festival, to Gwara Media.

Russia attacked Kharkiv relentlessly since the start of the full-scale invasion. In 2022, Music Fest’s team planned the concerts of Lucas Debargue and Nils Wanderer, but had to cancel everything. The festival still happened — in the Kharkiv subway with the symbolic name “Concert between explosions.”

“It should have been a set of events introducing world-famous musicians to Ukrainian fans of classical music. Now, we can’t invite most performers because of war, but we got a new meaning for our festival. The Kharkiv Music Fest is a powerful “code” of our city’s revival, which can fill the empty souls of Kharkiv locals affected by the war,” said Polituchyi.

In the following years, the Kharkiv Music Fest was held under this new motto — revival — uniting those who stayed or come back to Kharkiv, performers, and guests.

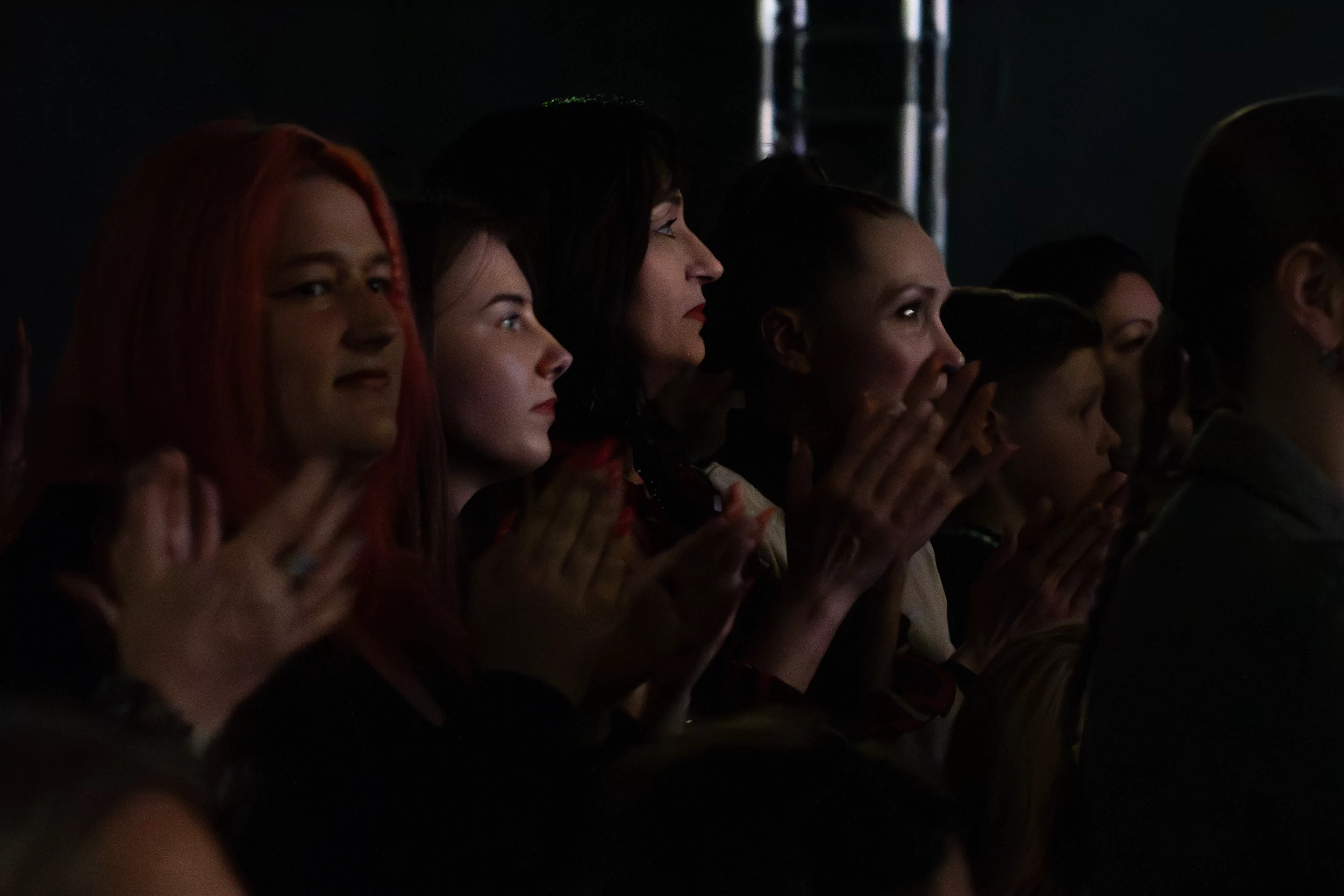

Today, almost all theatrical plays or music shows in Kharkiv begin by the audience going down long stairs to the underground stages, so that performances and the joy at watching them aren’t interrupted by air raid alerts.

The Kharkiv National Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre started hosting its opening concerts — it’s one of the few safe venues of the city.

In 2025, the festival’s theme is “The CODES of revival: Gratitude. Calmness. Harmony. Experience. Hope. Tradition. Reflection. Empathy” — and performers aim to uncover how emotions of our time are expressed through music.

The most famous Kharkiv Music Fest initiative is art-pianos placed around the city so that everyone could play under the open sky or in frequented public areas like university’s hall.

“It is an opportunity to be more open to people — and some of them improvise concerts at piano’s locations. I’m very happy to announce that there will be pianos at different subway stations this year. The first one will be at Yaroslav Mudryi’s station,” said Mariia Horbonos, the program director of the festival.

The National Ensemble of Soloists “Kyiv Camerata” opened the festival with the National anthem of Ukraine and expressing gratitude to the Armed Forces.

The program was divided into two parts. During the first one, Julian Milkis, a famous clarinetist from the States, played “Letters to Friends” by Georgian composer Giya Kancheli — a deep, emotional, and honest message, dedicated to the composer’s loved ones.

“This is my fourth visit to Ukraine during the war, and I realized that art and music are now as important as weapons. They give people the impulse to fight and live,” said Milkis.

Bohdana Pivnenko, the violinist (she’s called “Ukrainian Paganini in a skirt”) and Kateryna Suprun, the viola player, performed the second part of the opening concert.

“It is an amazing feeling to come to Kharkiv and see how people need art, music, and culture. All visitors returned after the break, and it says a lot. I’m happy to play for people who prove their unbreakability every day. Last year, we were afraid to come, but there weren’t any questions for this time because people and their emotions countered all (our) fears,” said Kateryna Suprun.

Pivnenko and Suprun played “Sinfonia concertante for violin, viola, and orchestra” by Valentyn Bibik, the world-known composer from Kharkiv.

The performers also said that, in Kharkiv, people react more emotionally to the music by Ukrainian composers than elsewhere — probably because of the close frontline and constant Russian attacks.

Ukrainian classical music, though, is now living through revival globally.

“Many Ukrainian classical compositions are performed now (compared to pre-full-scale war), which is very pleasing,” Bohdana Pivnenko says, adding that she feels like the Ukrainian classical music got more popular not only abroad but within the country.

At the end of the concert program, “After reading Lovecraft’s” by contemporary Ukrainian composer Oleksandr Rodin was played in Kharkiv for the first time. The audience heard a mysterious reflection of Lovecraft’s horror stories philosophy, realized through the sound of string orchestra.

Gwara Media talked to people in the audience — they said they enjoyed the professionalism of the soloists, got curious about the concert program, and resonated with the importance of Kharkiv Music Fest’s idea.

“I have been to all the events of Kharkiv Music Fest. I’m a real fan of the team and their work. Art is our cultural defense, and we try to show our resilience through these new meanings. We are not just surviving, we have (methods) of revival, and music is one of the symbols of future Ukrainian renaissance here,” said Volodymyr Chystylin, journalist and activist.

Locals think that Kharkiv Music Fest is vital for people who are subjected to Russian aggression every day.

“We really need music now because it supports our spirit. It is very important to us because life under attack is difficult,” said Kateryna, one of the visitors.

Mariia Horbonos said that the registration for the Music Fest’s opening was closed in one day because the “loft stage” has seat limits. She invites guests to other events of the festival, noting that all of them are free (but require registration.)

The Kharkiv Music Fest will continue from May 2 to June 10, and each event will be connected with a certain “revival code.”

The organizers said that the schedule could be changed because of the city’s safety situation.

In the evening of May 2, after the festival opening concert ended, Russia attacked Kharkiv with drones. More than 17 explosions followed the sounds of music. Russian drones injured more than 50 people, including two children.

Read more

- “I cried when I saw Kharkiv laugh again.” Nina Khyzhna on how Nafta Theater embraces changes that come with war