UKRAINE, KHARKIV — “How does it happen? Traumatic amputation at the frontline, stabilization point, our main hospital, and then surgery. We start working with soldiers as soon as they arrive,” explains Anastasia, a psychologist of the rehabilitation department in Kharkiv. Behind her, the wall is completely covered with flags from various Ukrainian brigades, some of them signed.

According to rough estimates, 100,000 people in Ukraine have had limbs amputated because of Russia’s war. Many of them are veterans. All require rehabilitation and prosthetics. This department’s team helps them recover while they go through both.

Dmytro is leading the team, and four people from his family are in the military. He says, “I know that no one will help them but me.”

Place to rebuild patients’ lives

Ukraine does not have a closed rehabilitation cycle, so a new rehabilitation department covers every phase of it. During the pre-prosthetics stage, Anastasia and her team focus on both the physical and psychological preparation needed for successful prosthetics.

Dmytro, putting on his medical gown, shares that the most important thing is to explain the patient’s treatment plan right from the beginning. The team tells the veterans what the prosthetics process will look like and what will happen while they are still in surgery.

“And the most enjoyable stage is when he comes back here later, without crutches, on his own. And like a happy child, he smiles and says, ‘Look, look, I can do it.’ That’s really the best moment of all,” Dmytro shares with a smile.

Lina, the ex-head of the rehabilitation department, vividly remembers the earliest days of planning to open it. Back then, the hospital faced many challenges: outdated equipment, limited funding, and a lack of trained staff. She often reflects on how difficult it was to convince everyone that such a department was necessary. “I kecpt saying, ‘Patients need more than immediate care; they need a place to rebuild their lives,’” she shares.

Lina and her team had spent countless hours discussing layouts, therapy programs, and staff roles. Gathering resources felt overwhelming at times, but Lina had been reminding her colleagues, “If we don’t start now, patients will keep missing out on proper recovery.” Training the new staff proved challenging as well, but she taught them to focus on skills and the importance of understanding the patient’s journey.

Opening the department to the first patients was a deeply emotional moment for her. Line walked through the new space, watching patients begin their exercises and realizing that all their hard work had paid off.

“Before, everything was grey”

Andrii’s rehabilitation began right after surgery — his leg was amputated. The team came to him every day, he recalls. They talked a lot — about service, good moments, about what went wrong. “They didn’t just treat my body, they helped me find myself again.”

Early on, his physical therapist started helping him to rebuild strength and coordination. They gave Andrii exercises, took care of his stitches, showed him how to move again. Everything was to help him recover faster and get ready for the prosthesis.

When asked about difficulties, he smiles: “Honestly, nothing was too hard. The team had a great sense of humor. We joked, we laughed — that made everything easier.” Humor became his way of staying grounded. “I’ve always been a cheerful person. Laughing helps you not to give up.”

Over time, rehabilitation became more than just training — he built connections with other veterans. “We understood each other without words. Some of us had similar injuries, so we shared advice and stayed in touch even after leaving rehabilitation.”

Archery and fitness became part of his routine too, and he joined a pottery class. “It’s not just about clay,” he explains. “It’s about peace. You leave the hospital building, talk to people, make something with your hands — it helps you forget everything for a while.”

After rehabilitation, Andrii’s world has changed: “Before, everything was gray. Now it’s colorful. I travel, meet people, and do sports. I spend more time with my family. Life became brighter.”

Even though finding work as a veteran isn’t easy, he stays optimistic. “Some people still think that if you’re a soldier, you’re broken. But that’s not true. I just live my life — drive, work out, even ride a skateboard sometimes.”

The key thing for veterans undergoing rehabilitation, Andrii says, is not staying in isolation. “Talk to people like you, train, find what gives you joy. Life doesn’t end — sometimes it just starts again, only more colorful.”

“Forget you ever had it”

“When they cut off my leg, the doctors told me: ‘Forget that you ever had it.’ And I did. I trained my brain to believe that there’s nothing there anymore,” says Andrii. “Sometimes it feels like something itches or burns, but I know it’s just the skin or the scar. Some people get stuck on that feeling — they think the leg is still there. But I made myself believe it’s gone, and that helped.”

Andrii has never taken any medication for the pain. He had asked, but the psychologists from the rehabilitation crew hadn’t allowed it. Maybe that had been for the best, he says, since he went through the phantom pain on his own and felt good and comfortable now.

Psychologist Anastasiia says the approach to treating phantom pain varies for everyone.

“There’s pharmaceutical treatment — pregabalin, antidepressants, and other medications that can ease phantom or neuropathic pain,” she explains. But, since the phantom pain also has a psychological nature — it comes from the mind, trauma, and body memory, they offer psychotherapy, too.

Kostiantyn, another veteran, says that he also faced phantom pain after both of his legs had been amputated. “Sometimes I still feel that pain, especially after spending the whole day on my feet, when my legs are sore and tense at night. I lie down, start falling asleep — and then it once again hits his legs.” In his case, he adds, the pain is not so severe that it needs to be suppressed with medication.

After eight months of lying, Kostiantyn’s body had changed — he couldn’t sit; as soon as he did, he immediately felt dizzy. With the help of rehabilitation specialists, he relearned to walk, “They helped me sit, then stand. Slowly, I got used to being upright again.”

“All who keep moving forward come back to life”

When Kostiantyn started his rehabilitation, he also began working with a psychologist. “There was no real psychological help before that,” he says. “They said (in the first hospital) it existed, but no one had ever seen it.”

For Kostiantyn, the biggest problem wasn’t physical recovery, but the system that didn’t work properly.

“The time given for rehabilitation after an amputation is three weeks. After, they transfer you to a prosthetics facility, but that’s not enough time. The swelling hasn’t even gone down yet, so you can’t start prosthetic training,” he shares. “You’re just sitting there for weeks doing nothing.”

Despite the inefficiencies of the system, he’s grateful to some professional specialists he’s interacted with along the way. “They are young, dedicated, and they really care. We still keep in touch, and they’ve become my friends.”

Kostiantyn spent eight months in a single room, and psychologically that was very difficult. “You need someone to talk to, ideally someone who’s been through the same thing.”

So, as he progressed through the rehabilitation, Kostiantyn began helping other veterans in free time.”There’s very little information about prosthetics. When I was there, no one told us anything. Now I try to go back and explain to the guys — it’s not a real leg, but you can live normally with it.” He adds that now he cannot do this much because he also has a job that requires his time.

Kostiantyn discovered the healing power of movement and community activities outside the hospital. “I tried archery,” he says. “It’s therapy. You feel control over your body again.” Even simple things, like going outside, to the sunlight and nature, helped him. The support of the family, though, was the most crucial.

When asked what advice he’d give others starting their rehabilitation, Kostiantyn doesn’t hesitate:

“Don’t close yourself off. No matter how good your doctors are, only you can help yourself. If you want to recover, you will. Even the best specialists can’t do it for you if you don’t,” he smiles slightly. “Everyone who keeps moving forward comes back to life.”

Staying detached is impossible

When patients come to the center, Anastasiia and her team try to understand what kind of difficulties they’re facing. Some struggle with adjustment disorders, others have acute stress reactions or post-traumatic stress disorder. There are also cases of depression. All of them need to be heard, Anastasiia says.

The rehabilitation here is built around multidisciplinary teamwork. “Each works from their own discipline but towards one direction,” she explains. “We have a wonderful military psychiatrist who provides us with consultations. Without medication, it’s often impossible to treat some mental disorders — psychotherapy alone isn’t enough.”

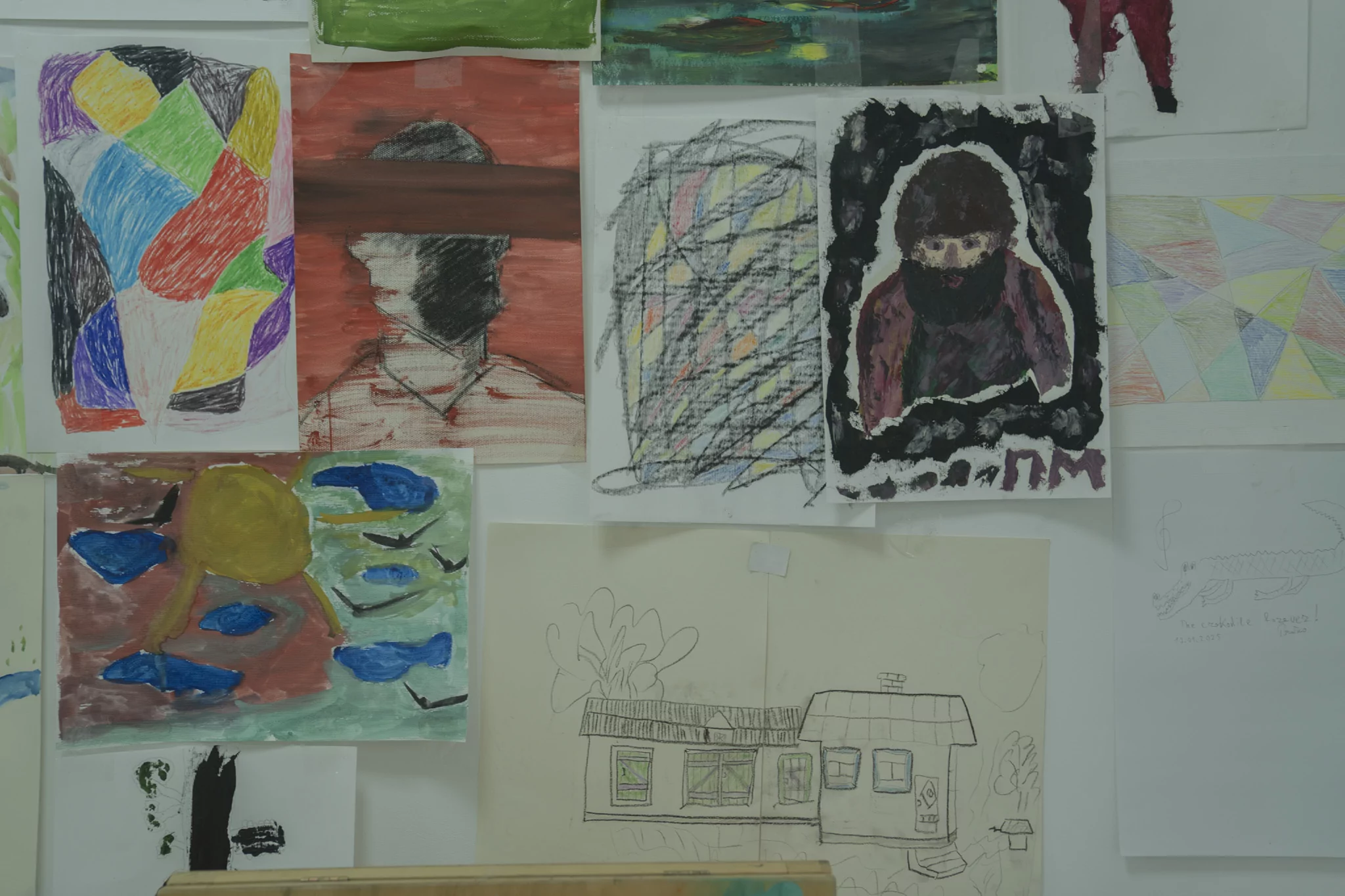

In addition to traditional support methods, the rehabilitation team uses non-traditional approaches for the emotional recovery of veterans, including canine therapy, hippotherapy, and archery classes.”

The work is emotionally demanding for everyone involved. “I don’t cry with my patients,” Anastasiia admits, “but sometimes I cry at home. You can’t go through this job without taking on someone else’s pain. We work with them for at least two weeks. Some become like family. Staying detached is impossible. Maybe it’s not about tears — it’s about deep empathy. That’s definitely our story.”

Humor, she says, often becomes a kind of a shield. “Soldiers and medics have very dark humor, but it’s a protective barrier — for them and for us. The patient shouldn’t feel like a victim. He should feel like a person. And our goal is to make sure he feels that — not just here, but when he leaves.”

For many, the most difficult part begins after being discharged. “Rehabilitation is a hard path,” Anastasiia reflects. “When a person loses their inner foundation, they look for support on the outside. Our physical therapists often become that support, even friends. And we try to do the same — to be that point of stability while they rebuild themselves.”

Cover photo: Veteran exercises on a simulator with a rehabilitation specialist / Nazar Hlamazda

Hello, this is Nazar, a journalist and author of this article. For me, this story is yet another example of the resilience and courage of Ukrainian society. If you want to support Gwara’s journalism, buy us a coffee or subscribe to our Patreon.

Read more

- Kharkiv recruitment center’s employee found guilty for punching civilian after checking his military registration documents