AUGUST 11 — Tetiana said she and her partner felt the situation in Kupiansk changed about two months ago — the number of Russian airstrikes started to increase, and essential services got cut off one by one.

What moved her and Serhii to evacuate, though, wasn’t the danger of drones or lack of customers in her shop. It was Russian soldiers coming to ask for cigarettes.

“I was at work, it was a quiet day. Two men came in Ukrainian uniforms but wearing Russian armored vests — my husband knows about this stuff. I heard the Russian accent. They asked for cigarettes,” Tetiana said. “They didn’t have money. I got suspicious — usually, people ask to pay with the card. Back then, they sat on our shop’s veranda and started to tell people that they were from Russia.”

“(Russian soldiers said) ‘We came to liberate you,’” Serhii quotes.

Serhii and Tetiana evacuated from Kupiansk to Kharkiv on August 5 — that’s when Gwara’s journalists talked to them, in one of the evacuation centers in the city.

Kupiansk was one of the first big cities Russia occupied at the beginning of the full-scale invasion — but Ukraine’s forces pushed them out of the city and beyond the Oskil River that splits it during the Kharkiv counteroffensive in autumn of 2022.

Since then, Moscow wanted to reoccupy the city, important for logistics and transportation of the region. After a failed breakthrough to Kupiansk’s outskirts last September, they renewed their effort this spring.

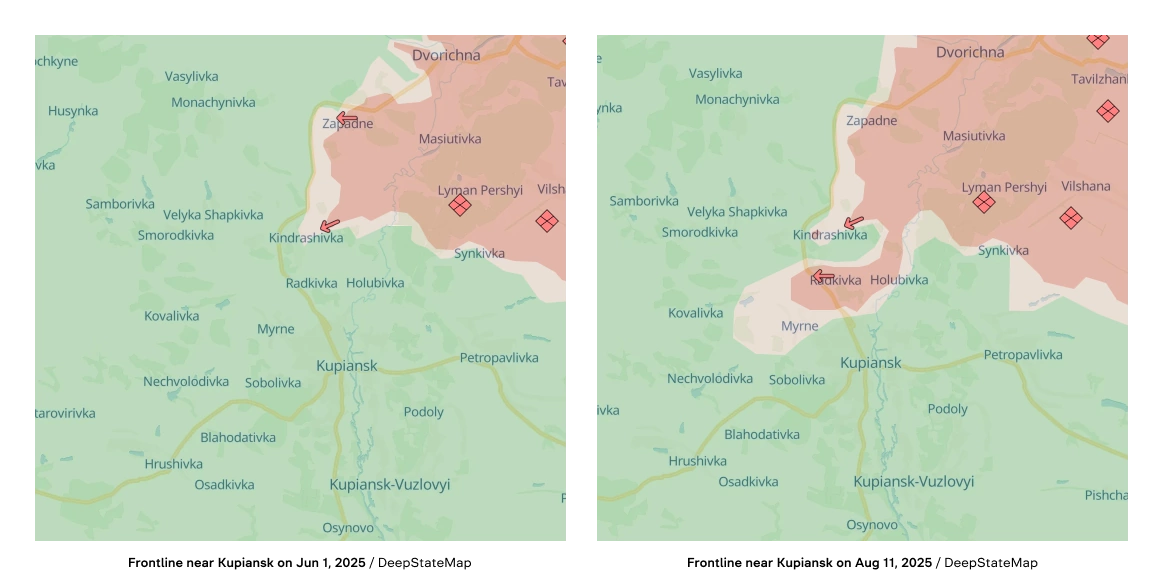

In the middle of June, they completely occupied Dvorichna, northeast of Kupiansk. Then in July, through the small grinding advances, Russia entered several villages north of the city, which gave their infantry an easier way to approach the northern part of Kupiansk, including on the right bank of Oskil.

Though Ukraine’s military and open sources still report heavy fighting in this area, these advancements have deteriorated the situation in the city, endangering 1,100 civilians remaining there — along with the logistics of the entire region.

To Tetiana and Serhii, Russian soldiers bragged about how they’ll connect electricity and gas in Kupiansk and launch a Russian mobile network.

“That’s when we thought: we must get out of here,” Tetiana concludes. “I was most afraid of their behaviour. One was constantly playing with the knife, another — with a breach block. I’ve never seen our boys behave like that.”

Tetiana and Serhii reported their encounters with Russian soldiers to Ukraine’s military at the first checkpoint out of Kupiansk.

Sabotage groups

Seeking a quote from Kupiansk authorities about Russian sabotage groups in the city, Gwara’s journalists contacted Andrii Kanashevych, the head of the district military administration.

“That’s some kind of another fantasy,” Kanashevych said. “I don’t have information like that. We understand what a sabotage reconnaissance group is, right? They wouldn’t go to the shop, wouldn’t show themselves to locals. They would quietly get in and quietly get out.”

Then, Gwara spoke to four servicemen: three of them — from units stationed in Kupiansk or defending it, and one — serving in the aerial reconnaissance unit that covers this section of the Kupiansk axis. All of them confirmed the presence of Russian sabotage reconnaissance groups in Kupiansk.

They agreed to speak on condition of anonymity.

“I do know about sabotage groups in the city,” said the commander of the FPV drone team working in Kupiansk. “The group I’ve heard about was destroyed (5 killed, one captured). I don’t know about others, but in every frontline city, you should expect them.”

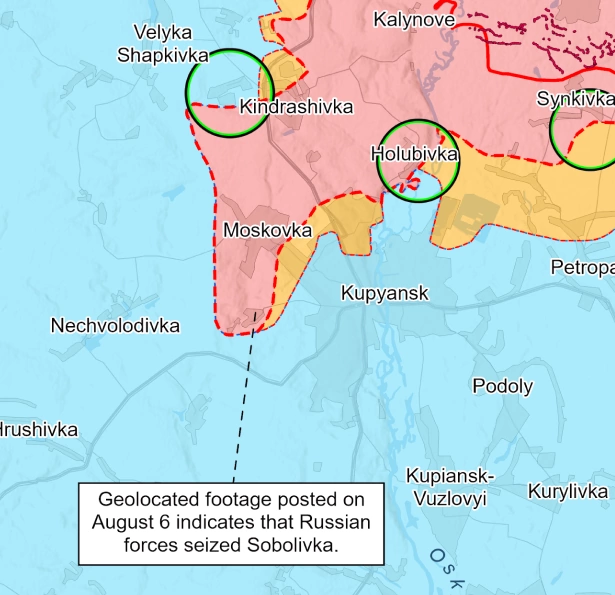

A senior sergeant of a drone unit from another brigade said that Kupiansk was flooded by Russian sabotage troops when one of the Ukrainian brigades “broke the defence” in the north of the city about three weeks ago (he refused to disclose the name of the brigade publicly).

Now, he said, some of the nine-storey apartment buildings on the northern edge of the city are controlled by Russians — and some of their sabotage groups were being caught as far as Nechvolodivka, the village west of Kupiansk.

“Currently, some of the Russian soldiers are being caught and destroyed, but there are way too many of them.”

The drone unit’s sergeant said that, for now, Ukraine’s forces in the city are trying to deal with Russian soldiers in Kupiansk through various kinds of air strikes because of the lack of infantry.

When asked why Russian sabotage groups would interact with the locals, one of the servicemen we’ve spoken to suggested trying to invite collaboration.

Changing clothes is a standard tactic, the senior sergeant of the drone unit said. “They don’t want us to find them.”

Approach from the west

Kupiansk, being a relatively big city and a logistics hub, is a target for all kinds of Russian airstrikes. Only in July, according to authorities, Russians dropped over 140 glide bombs on the city.

The commander of an FPV drone team says that Kupiansk’s defence is also complicated by how fast Russian infantry troops hide in the nearby forests, making them unreachable for drones.

“Now, they can put pressure not only on the river, but go around the city from the north, which is what they do now, as you can see from DeepState.”

A recent Institute for the Study of War (ISW)’s report talked about a confirmed Russian presence in Sobolivka, a village located immediately west of Kupiansk.

From there, analysts say, Russian soldiers can threaten Ukraine’s ground lines of communication — meaning the highway H-26.

This highway connecting Kupiansk to Chuhuiv has been the only safe “entrance” to the city, supplying it and the villages on the left bank of the Oskil River since Russian troops started to advance towards it. It is also the safest evacuation route.

A reconnaissance unit’s soldier told Gwara that the most likely scenario here is for Russia to circle the city from the west to the south and envelop the city.

“Envelopment has been their main tactic for a long time,” he said. “They have no reason to go (into frontal assault) towards fortifications, it’s better to circle (the city), envelop it, cut off the logistics.”

ISW analysts agree with this assessment: they say that Russian advancement in the northwest of Kupiansk would support efforts to envelop the city and hurt Ukrainian troops’ supply chains.

Even now, supply and logistics are challenged by Russian remote mining and FPV drones — including those that are “sitting” on the road in wait for upcoming vehicles, says senior sergeant of a drone unit, adding:

“If they’ll cut off H26 road, we’re screwed.”

Not letting heavy equipment pass

“Their advance is slow, but it’s ongoing,” says the commander of an artillery brigade stationed in Kupiansk. “But the defence of the city will continue — for now, the enemy doesn’t have a chance to get close to the city or encircle it.”

The soldier from the aerial reconnaissance unit was not ready to make predictions but noted, “Russia has enough strength, and enough specialists, including drone specialists. If we manage to protect Kupiansk, it will be a miracle.”

One of the main Russian efforts right now — and has been, since they’ve successfully crossed Oskil near the city during winter — is to try to send heavy equipment on the right bank.

“On our (right) bank, Russians already have motorbikes and mortars,” said a senior sergeant from a drone unit. “On average, every unit stationed (near or in Kupiansk) burns down three or four boats per day. The next day, new boats appear.”

Sometimes, Russian troops try to build a pontoon bridge or at least jump over Oskil on the armored vehicles, he says. Ukraine forces’ main job is not to let them through.

“The enemy is constantly doing engineer reconnaissance,” said the commander of FPV platoon with a “Mahnit” call sign to Armia TV on August 8, adding that, for now, all attempts to send heavy equipment across the river were halted by the Armed Forces.

“The main task for us is not to allow heavy equipment. While (Russians have) infantry on motorbikes, they’ll be advancing, sure, — there are simply more of them. But if, God forbid, we let heavy equipment pass through, I’m afraid they’ll stop somewhere in Shevchenkove,” a senior sergeant said. (Shevchenkove is a village on H-26 highway — the village stands on the next height to the west after Kupiansk.)

A soldier from aerial reconnaissance said that the main challenge in defending the city is lying: “When some bosses are afraid to tell the truth to the other bosses so as not to get in trouble. And those lies are then sent upwards.”

The commander of the artillery brigade, when asked about challenges, said that Ukraine is repeating the mistake of 2023 — underestimating the Russian army.

“The enemy has adapted for this war. They increased production, their economic system works for the military effort, they modernised their army’s management. Unfortunately, I do not see the same thing in the Armed Forces of Ukraine.”

With Russian soldiers in the villages north of Kupiansk and Ukraine’s lack of infantry and service people in general, three of the soldiers we’ve talked to referred to the situation in the city as, paraphrased mildly, extremely challenging.

When asked about how the situation — with the increasing number of sabotage groups and constant attempts to cross the river — can be improved, the senior sergeant, who has been fighting against Russia since 2014, said:

“I hope they send an assault brigade here. Because the experience of many years showed that if Russians have grabbed onto the first buildings in any settlement, you can only physically push them out of here. No FPV drones, ground robots, explosives, or artillery can help — you have to go there and take them out.”

Hi, it’s Yana Sliemzina — and I wrote this article for you to get a grasp on what’s happening in Kupiansk. Thank you for reading it. Russian advances may seem slow in this section of the frontline, but, like one of the soldiers I’ve talked to said, slow advance is still an advance. If you want to support our Kharkiv-based newsroom as we cover Russia’s war and life amidst it, please consider buying us a coffee or subscribing to our Patreon.