UKRAINE, KUPIANSK-SVATOVE AXIS — Night is dark and moonless, so to reach their 120mm mortar, soldiers of the 44th separate mechanized brigade have to navigate the path using red lights. Anything bright is dangerous, even amidst the dense foliage of the nearby trees—too visible for Russian drones constantly flying over the unit’s positions.

They load the shell into a mortar, and the unit commander, a friendly man with a call sign Ivanych, orders fire. A ruffle, a dull sound. Crickets sing in the grass.

“Sashko, what happened?”

“Has it fired or not?” prompts the voice from the radio.

It hasn’t. The shell got stuck in the mortar. Ukrainian soldiers call these cases, squib rounds with pop and no kick, “abortion.” After that, four mortarmen have to disassemble the mortar with a tube weighing 80 kg and take out—very carefully—a 16-kg shell.

“First time it happened, we were scared to do that,” Ivanych comments after the “aborted” shell is safely tucked away into a “defect” box. “Took us a long time. Now, we can do it in two minutes.”

Today, this unit’s mortar fired 17 times, and three of these shells got stuck. After removing the shell, they have to put in a new one, find their target, fire again. Although now the process takes minutes because soldiers got used to it, even the slightest delay is dangerous.

“The enemy can relocate, move forward during that time,” Ivanych says. “That is not good.”

Usually, where their unit takes time to fix the squib load, other troops in the area—artillery troops, mortar crews with 80mm mortars positioned closer to Russians—cover for them. This unit’s main task is to cover Ukraine’s infantry: people who prove vital defense and carry the spears of any offensives.

On May 10, Russia launched the first major ground offensive since the start of the full-scale invasion, moving deep into the Kharkiv region from the north. One of the major goals of this move was to stretch the frontline and, therefore, Kyiv’s forces.

While the Donetsk region and frontline near Pokrovsk and Toretsk felt the impact of the Kharkiv offensive the most, as Ukraine relocated several of its brigades to protect Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second city Russian attacks also intensified on the Kupiansk axis.

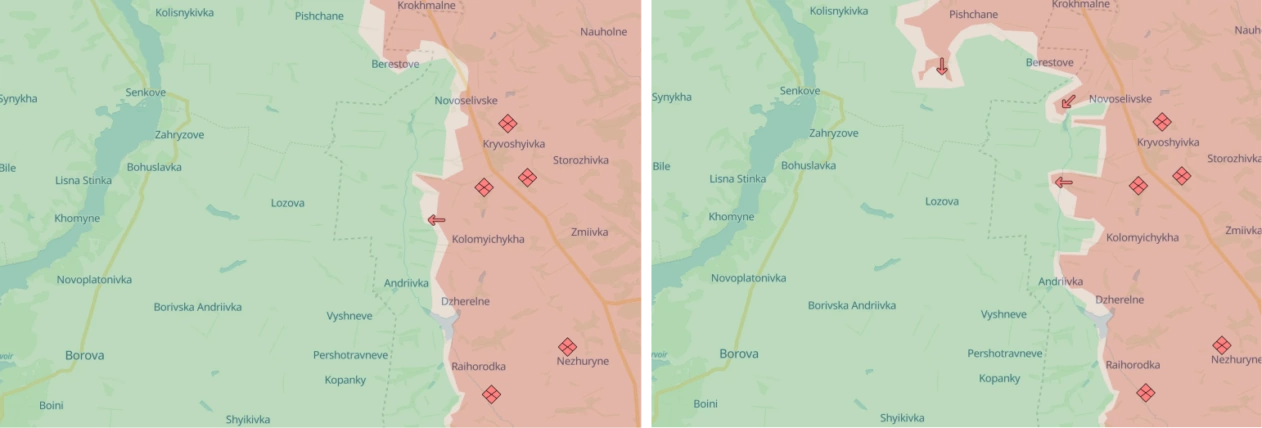

Since May, Russia advanced in some sections of the Kupiansk axis — towards Stelmakhivka, Stepova Novoselivka, Kolisnykivka, Kruhliakivka, and Lozova — and occupied Pishchane. In this direction, Russia tries to seize the rest of Luhansk Oblast and gain ground in Kharkiv and Donetsk regions, targeting Kupiansk, a once-occupied railway junction northeast of Kharkiv City.

The commander of a mortar battery from the 44th brigade, call sign Mishka, said to Gwara on September 3, that, while for the mortar unit we’ve talked to for this article, the situation is the same as in the beginning of August, Russian troops are pressing forward on the Kupiansk axis. In the southeast section of it Russians “have successes” west and southwest of the occupied Pishchane and northwest of occupied Kolomyichykha.

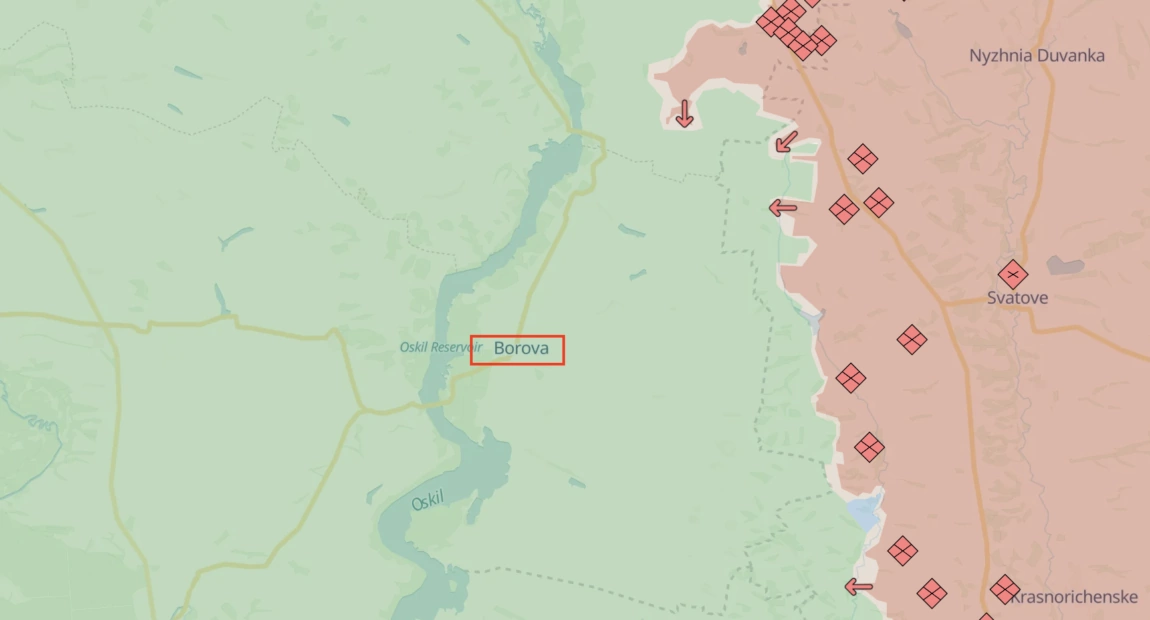

In June, military and Kharkiv local authorities said that the next target of Russia’s assault on the Kharkiv region might be the settlement of Borova. DeepState released a report saying 10,000 Russian troops are prepared to move towards the city. Serhii Zgurets, CEO of Defense Express, wrote that, with the strike on Borova, Russia might aim to “split” the Kupiansk—Kreminna line in two, complicating Kyiv troops’ logistics.

Whatever shell available

The only way to reach the positions of Ivanych’s team is at night, while the driver of a loud military vehicle, call sign Boroda, wears a thermal imager to see the road. During the day, Russian drones target everything that moves here.

When the car battery overheats and dies, the car stops on the dirt road. Boroda and his second move around quietly in the red light to find another one. The search is followed by soft banter, curses. A pause. With a new battery installed, the car lets out a pitiful, bubbling sound, but accepts it. It’s lucky. One really shouldn’t stay here, out in the open field.

They drive forward to distribute newly arrived shells among other mortar crews stationed here.

“What have you got there?” Ivanych asks, as his unit examines the new supply of shells that need to be carried close to their mortar. Everything needs to be at hand for when their next target is spotted.

“Well, it’s this fucking joy,” a soldiers waves at the box.

When Ivanych sees the shells inside one of the boxes, he sighs, “Well, we can leave these here.”

The problem with India-manufactured projectiles, he explains, is one of the reasons of “pop and no kick” unit faces so often: their ignition cartridge is too low. Soldiers need to readjust the cartridges manually to use them. Like dealing with the stuck, “aborted” projectile, it takes precious time and is extremely dangerous.

“We use what we’ve got, though,” Ivanych says.

A normal number of shells to use in a day, the unit’s commander says, is 24-28. One of the soldiers from the brigade told Gwara that during the long period when U.S. military aid was stuck in Congress — and the EU couldn’t procure the 1 million shells it promised — they had days where they could only use 80 in a week.

While Russia can afford to do aiming shots and then use 20 shells per attack with their automatic mortar, for Ivanych’s mortar crew it’s a luxury. He explains, “We’ve just received ten shells [for the next day]. We have to know the target’s exact location if we are to shoot at it. If we don’t, the command will think about whether to use them or not.”

An assistant to a mortar crew with a call sign Frenchman doesn’t exactly feel the difference between times of shell hunger and now. The lack of mines, he says, is still the main lack for a unit.

No newly drafted

Almost everyone in the unit, the main “skeleton” of the brigade, are people who have served since 2022. Some volunteered, and some were drafted in 2022. Some, like Pole, have already fought against Russians in 2015. He marvels at how peculiar it was, to see the same places nearby Svatove six years after demobilization.

“Do you have people who have been recently drafted? Just after training?”

“I haven’t seen even a single one in my time,” Frenchman, who’s been here for almost two years, says. “Four were transferred from other battalions, units. They serve a bit with us, then they get transferred again.”

“Five of us have to be in the mortar crew, but lately, only three of us are working. Because there are no people,” Ivanych says, describing how eight people from his team got injured in the Russian drone attack on one of their cars. He agrees: “new people” aren’t joining.

“Those who wanted to join have joined already,” Frenchman says.

“When I get home, I am constantly stuck in traffic,” a soldier from the Kyiv Oblast says. “When the war started, you could play football on the empty roads. Now, there are traffic jams—and they don’t have people to draft! I wouldn’t say only women are behind the wheel. People are hanging out.”

A day of rest, for some

At the shuffling within the walls of the mortar team’s dugout, Boroda chuckles, “Ah, the residents,” he explains, “Rats and mice. Our tailed friends.” The dugout has five beds—a cat named Muryk is languishing at one of them. The place smells of earth and coffee.

Russian tanks destroyed this team’s previous dugout completely; they dug and built another one this spring. FPV drones and glide bombs hit near their position often, Anastasiia, 44th brigade press officer, says.

You have to be careful in the quiet, too. Russians use Orlans [Russian air reconnaissance drones — ed.] — and unlike FPVs and glide bombs that can be heard from a distance, Orlans are silent; they fly very high. Orlans guide Russian artillery and mortars, their tanks. A tank’s first shot is terrifying, Ivanych shares.

“Danger is the most difficult part of this work. The necessity to hide,” he says. “We can work, we’re used to hard work. A dangerous, tense environment is very tough. Shelling, FPVs…”

Tension, along with hard work, exhausts. Mortar men of the team have to work six days per week and have only one weekend. Two drivers of 44th don’t even have that—they are constantly on call. “You’re sleeping with the radio.” The other two drivers from the unit are currently repairing the brigade’s vehicles, which is also a laborious process.

“I want to go home. I am sick of all this,” Frenchman says. “My wife has left me, so I need to find another.”

“People go on vacation to rest, relax. You went to get a divorce,” a driver, call sign Pole, says. Soldiers laugh.

The last time any of the team were on vacation was in May, before the beginning of Russia’s offensive from the north.

During the one weekend they have, they go to a nearby village: to buy groceries, do laundry, call or write to their loved ones—where they are now, the mortar unit doesn’t have any access to the internet or cellular connection. Every device is in airplane mode because of safety considerations.

Free time passes quickly.

The watch duty for one person—listening to the radio for orders and information—lasts two hours. “If you’re lucky, you can sleep for six hours,” Pole smiles. Sleep is a preferred way to spend free time here.

“The cat feels better than anyone,” the soldiers conclude, laughing.

No one allows himself to think about what they will do after demobilization, after they catch up on sleep on the proper bed.

“It’s difficult to think about,” Pole says. “Impossible. You think of how to stay alive… And everyone here probably thinks like that.”

Staying alive and working efficiently became more complex with how the Russian-Ukrainian war changed over the last two and a half years.

“On every action, there’s a counter-action,” Ivanych muses, recalling how drones were countered by electronic warfare (EW) methods, and those were countered by more advanced drones working on different frequencies.

“Everything is being modernized. New things don’t live for more than 1-4 months. It’s a race, everything updates.”

Ivanych mentions Bayraktars, which damaged Russian equipment so much at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Now, they are shot as soon as they rise in the air.

“And they cost insane amounts of money. It’s such a waste. Although everything is a waste of money at war… But we, for one, are protecting our land, and them? Want to take it away, bite off what they shouldn’t.”

Cover photo: Soldiers of mortar unit of 44th Separate Brigade of the Armed Forces on the Kupiansk axis / Photo: Denys Klymenko, Gwara Media

Hi, I’m Yana Sliemzina, and, along with Denys Klymenko, Gwara’s videographer, I went to speak to the 44th brigade’s mortar crew about their work, their life, and war. Thank you for keeping an eye on the Kupiansk axis among a multitude of things that are currently (very quickly) happening in the Russian-Ukrainian war. Please, consider also supporting our reporting on Patreon, BMC, or PayPal.