UKRAINE, SLATYNE — The car accelerates from Derhachi north of Kharkiv along the highway towards Kozacha Lopan, a village located one mile away from Russia. “Unbuckle your seatbelt,” the driver says, hitting 75 miles/hour. Rules don’t apply here and you have to be ready to jump out of the car at once after spotting a drone. Military vehicles speed past the car towards the city.

Five civilians have been killed in Russian drone strikes here over autumn, say local officials. FPV drones lurk on the roadside and rooftops, hunting vehicles. Anti-drone nets are being installed, but progress is slow under constant surveillance.

Russian forces monitor everyone entering or leaving the border villages. Five hundred residents remain in Kozacha Lopan without electricity, gas, or signal. Unable to reach them, aid workers leave supplies in nearby Slatyne, 13 km (8 miles) from the border, where residents go to pick up humanitarian aid and pensions.

Gwara Media met Kozacha Lopan locals there and spoke with them to learn why they keep living so close to Russia.

Living on the edge

Slatyne greets visitors with a deserted railway station—weeds now grow between the railways tracks, and all that remains from the station’s building are crumbling walls bearing inscriptions: “Welcome to Hell” in Ukrainian and “Welkome to Ukraine, bitch” in English.

Since July 2025, the station in Slatyne is the last stop on the way north from Kharkiv. Trains no longer run to the border villages of Kozacha Lopan and Nova Kozacha (neighboring village, 4.3 miles from the border) due to the constant threat of Russian shelling.

Instead, a dozen residents from the border area come here for humanitarian aid—by cars, motorcycles, or bicycles. They pack the bread into bags for themselves and for people who have stayed in their village.

There are no shops, pharmacies, or post offices in Kozacha Lopan. Utility services no longer operate there, and even medics, police, and local authorities have relocated farther from the frontline because Russians increased drone activity and expanded the killzone near the border.

“We’ve been abandoned. They tell us, ‘Evacuate, you’re just waiting for the Russians.’ But we’re not waiting around for anyone. We were born here,” says Valentyna. She wears a neat cream-colored hat, holding a black bag she used yesterday to carry medicine to elderly neighbors in Kozacha.

Mostly elderly people remain in the village. Evacuating them requires “two strong men,” Valentyna says, but they won’t go because of the drone threat. Plus, elderly and disabled people cannot care for themselves in the dormitories where authorities typically place evacuees.

“People will simply freeze here. Today, a disabled neighbor wanted to go with us to Slatyne. He was shivering with fever. Where will he go? He’s 58, deaf, and cannot speak. We provide for him. We understand him. No, he won’t go anywhere — and there are others like him who won’t leave.”

Human hunting

In early 2022, approximately 5,000 people lived in Kozacha Lopan, but the population has declined tenfold since, according to local authorities.

Valentyna says that around 600 people remain in the village—some male residents avoid registering for humanitarian aid out of fear of military conscription.

Russian reconnaissance drones constantly circle above, watching locals. “They already know where everyone lives,” says Nataliia, slightly younger than Valentyna, wearing a bright pink backpack with a yellow and blue ribbon tied on it.

“Are the Russians also attacking the road to Slatyne (with drones)?”

“The problem is that military vehicles drive by, sometimes civilian ones too. And both get hit.” the local women reply.

Suddenly, one of the women who had been silent speaks up. Vira’s voice is quiet and breaks often as she talks about her husband, who was killed last summer by a Russian drone strike while they were driving to another village to pick up hot meals.

“The drone caught up with our car. He died. We buried him in Nova Kozacha. No one wanted to go to Kozacha Lopan,” Vira says, hand reaching to cover her mouth. Her eyes glisten with tears.

In two years, about a hundred people have died from Russian attacks, locals recall. Some were buried at home, others in nearby villages. The funeral service, too, no longer comes to Kozacha Lopan.

Valentyna says that, despite all of that, they keep delivering meals and humanitarian aid back to Kozacha, refusing to evacuate. Being on the road is scary. Sometimes they drive under the drones, sometimes they turn back home empty-handed. Each of these trips could be their last.

Cellar dwellers

Kozacha Lopan was once bustling with life—it had a border crossing with Russia and a customs office. The Kharkiv-Moscow highway ran through the village, with intense traffic in both directions.

Russia occupied the village on the first day of its full-scale invasion, repainting the Ukrainian flag on a mural with the inscription “There is no end to the Cossack kind” in Russian. The Ukrainian military deoccupied it after about six months during the Kharkiv counteroffensive.

Life in the basement is what life a mile from the Russian border is imagined to be like, but locals say they don’t stay there that much.

“We sat in cellars during the occupation because that was our only option. We couldn’t go anywhere,” Valentyna says.

There was no bread at first. Valentyna had only one package of pasta at home—why stock up when there’s a shop nearby, she had thought, and then the Russians came.

Locals scavenged abandoned farms for harvested wheat that was starting to spoil. They used it to make bread. Then humanitarian aid arrived, from Russia.

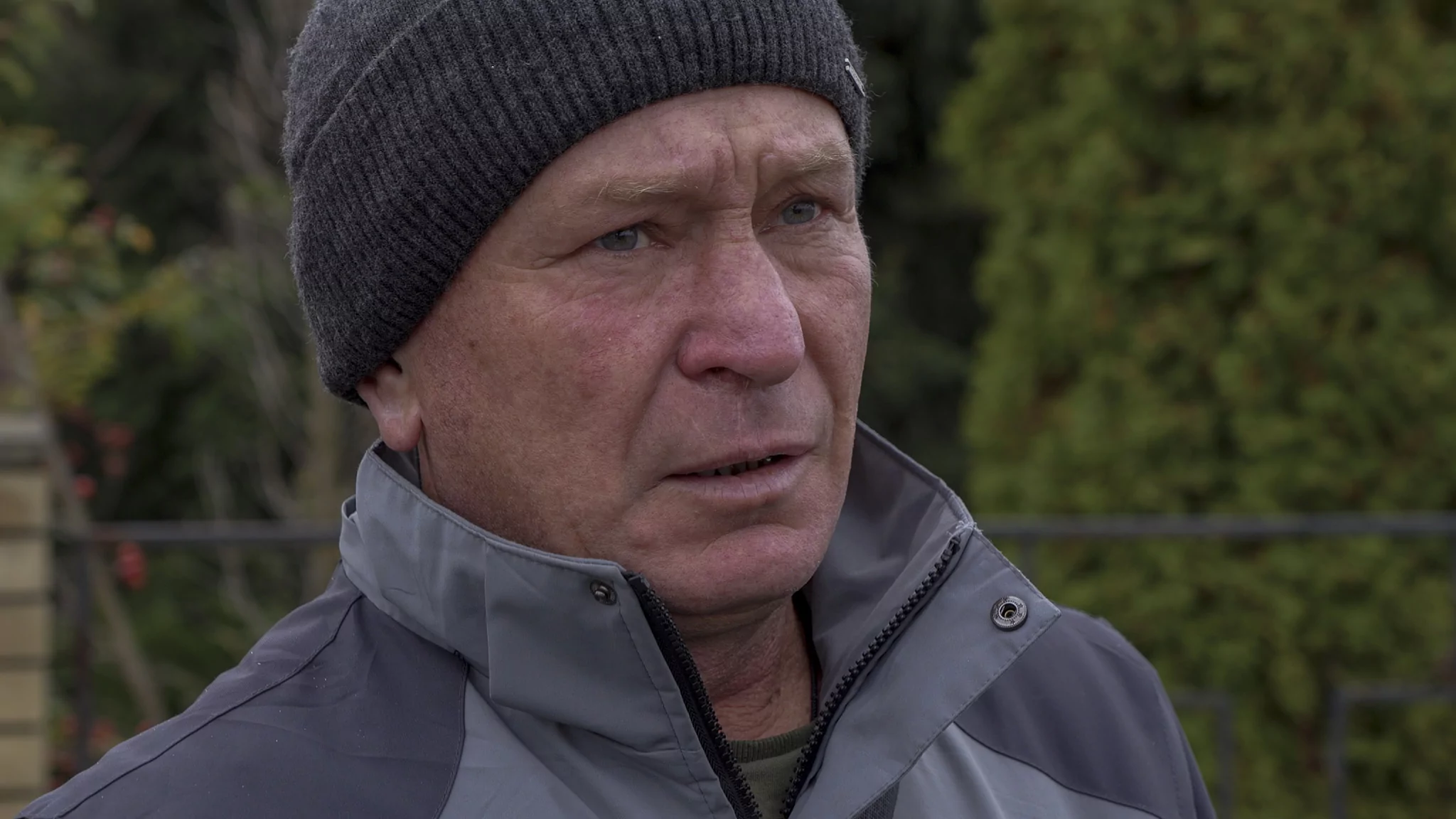

“It was very difficult. They turned Kozacha Lopan into something like a concentration camp: no one could leave or enter without a pass,” says Oleksandr, a lively man who used to pass information about locations of Russian troops to Ukraine’s military.

Locals say phones were checked by Russian soldiers, so they buried them. Valentyna sheltered eight people in her cellar—elderly and disabled. “We slept where I used to store sacks of potatoes.”

Winter is here

We ask Oleksandr how he plans to spend the winter. He lives with three elderly women—not relatives, but people he cares for. They received financial aid from the state to buy firewood, so he sounds calm compared to neighbors who complain they cannot get any.

Valentyna and Nataliia insist gas service can be restored—half the village was untouched by shelling, and locals have repaired all damaged infrastructure themselves, however amateurishly.

Kozacha locals gather around when the topic turns painful—they interrupt each other, talking simultaneously until their words blur together. They rush to share every problem in this brief encounter, hoping that it will help to change something.

“They cut off our gas before winter without warning—just abandoned us in September with no explanation,” Natalia says, indignant. “Nothing is damaged. There are no gas leaks.”

Without gas since early autumn, the village also hasn’t received firewood deliveries, because suppliers refuse to travel there even for money. So, locals cut down trees themselves and help those who can’t. Going deep into the forest is frightening—God knows what the Russians left there during occupation, they say.

“Who’s going to help us? Should we go to Russia, or what?” Valentyna asks.

Liudmyla Vakulenko, the village head of Kozacha Lopan, operating from Slatyne, says the locals are waiting for Russia’s war to end. “They won’t leave. The situation is extremely difficult. Food is being delivered, so people won’t starve.”

Many animals also remain in Kozacha—there are more dogs than people. Locals can’t abandon them. “People say they can’t leave behind those who won’t abandon them first. Without each other, both will perish,” Vakulenko says.

Liudmyla mentions one disconnected section of the gas system and hopes it can be repaired once there are fewer Russian attacks.

Gwara contacted the gas service about restoration of gas to Kozacha Lopan. They said that specialists haven’t fully inspected pipelines in three years because of the border threat. To protect employees, they suspended gas to Kozacha Lopan and neighboring villages and warned the heads of the communities about that.

Why they stay

Nataliia works as a hospital cleaner in Kharkiv once every three days, earning 5,000 hryvnias ($119). Each shift requires hiring a taxi, and the trip there and back costs 600 hryvnias ($14).

This money won’t cover rent and food in Kharkiv, Nataliia says. In the village, they have gardens where they grow vegetables to feed themselves year-round. Relying on children also isn’t an option. Natalia’s son works as a firefighter in Derhachi with a wife and two kids. The Russians destroyed both his houses—one in Kharkiv, one in Tsupivka, a village near Nova Kozacha. “He needs help himself,” Nataliia says.

Oksana doesn’t want to stay with relatives for long, either. “I can stay a few days, maybe a month. After all, I’m just a stranger.”

This year, several people left Kozacha Lopan—mainly those whose houses were destroyed. The rest hold on. Sometimes residents return to find their homes emptied by looters.

“Police don’t come here. All the looters are locals—try confronting them. They’ll file a report against you, and you’ll end up in jail,” Oksana says, aggrieved.

In his free time, Mykola—another elderly man from Kozacha Lopan, US cap on his head—reads newspapers and books, watches pre-downloaded news or movies. He and his wife can’t walk around the village anymore because of Russian drones. Starting over somewhere else, he says, is physically and morally impossible.

“If I were young, I’d go somewhere, do something… But at 60, where can I go? Who will hire me? I have rheumatism and radiculitis. Today, I work—tomorrow, my back hurts. I don’t want to let anyone down,” he says.

“It’s scary,” Oleksandr repeats, like everyone else. He wants to leave, but can’t abandon his grandmas. One of them has two apartments in Kharkiv, yet refuses to leave Kozacha. “Some have nowhere to go. Others could leave, but won’t.”

Transport for dead and living

Valentyna picks up two packages and heads for the car. Nataliia and her neighbor Liudmyla walk toward a red motorcycle with a sidecar.

A man leans against it, smoking. His name is Serhii, and he assembled the motorcycle himself after de-occupation to leave the village and buy medicine for his mother Liudmyla, who had a stroke.

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, he worked at the cemetery, but now he transports the dead and living out of Kozacha Lopan—a job no one else would do.

“I’m afraid ‘katsaps’ (a swear word used for Russians) will hit me with ‘little planes’ and drones. They’ve chased me before,” says Serhii.

“Why were they chasing you?”

“To kill! They’re already targeting civilians. They don’t care,” his mother Liudmyla answers instead of him.

Among the bags they’re loading onto the motorcycle, I notice a yellow and blue bag with the words “Independent and Free Ukraine” printed on it.

“That’s how we ride,” Nataliia laughs. “Let the (Russian) reconnaissance drones watch.”

Serhii starts the motorcycle. Liudmyla shouts “Glory to Ukraine,” and their motorcycle pulls onto the road. They wave goodbye, then cross themselves before heading home.

Will flowers bloom again?

“When they leave, I pray every time to see them again, because there’s no way to contact them in the village,” says Liudmyla Vakulenko.

Standing beside her is Oleksandr Kulik, young head of communications for the Derhachi community. He’s skeptical of locals who criticize living conditions but refuse to leave.

His boss, Viacheslav Zadorenko, heads the Derhachi community and is a Kozacha Lopan native. In a recent interview, he shared that when people choose to stay in a community under constant attacks—where someone is killed or wounded almost weekly—and then complain to him about lacking electricity or gas, he tells them it’s their personal decision.

Zadorenko says people refuse to evacuate until their homes are destroyed, then demand rescue, forcing authorities to risk their lives under drone and artillery fire.

Kozacha Lopan’s center is really ruined, Oleksandr—a local who’s still in Slatyne—sighs. “It’s very hard when you remember how everything used to be. There are streets where not a single house remains intact—destroyed, burned down, or critically damaged. Sometimes nostalgia torments me. It’s very hard to see my village like this.”

“Are you afraid of another occupation?”

“I won’t go through occupation again—I’m in contact with our guys (Ukrainian soldiers). If it comes to that, I’ll evacuate the locals with them,” the man replies.

Despite everything, Liudmyla believes the village will be rebuilt, people will return, and flowers will bloom again.

“We just have to wait for the war to end. We live on the border, so we can’t run. Even those who left the country want to come home. We just need to wait a little longer for victory.”

Cover proto: Locals at the railway station in Kozacha Lopan. September 2022 / Photo: Oleksandr Magula, Gwara Media

This is Polina, the author of this text. We went to Slatyne together with my colleague Anna Veklych. It’s a relatively safe area where border residents come to receive humanitarian aid. Just a few hours after we left, Russian drones with fiber optics attacked the village center. If you found this text valuable, please, support our journalism by buying us a coffee or subscribing to our Patreon.

Read more

- “Whole world must see it.” Exhibition in memory of children Russia killed opens in Kharkiv

- Russian troops bomb kindergartens. Here’s how mother helps her son restore sense of safety in Kharkiv