Every year on the fourth Saturday of November, Ukraine commemorates the victims of the Holodomor of 1932–1933, as well as the artificial mass famines of 1921–1923 and 1946–1947.

The terrible Holodomor of 1932-1933 was killing Ukraine from April 1932 to November 1933.

During this period, approximately seven million people died of starvation in Ukraine, although the exact number of victims is still unknown. Kharkiv Oblast was one of the regions that suffered the most.

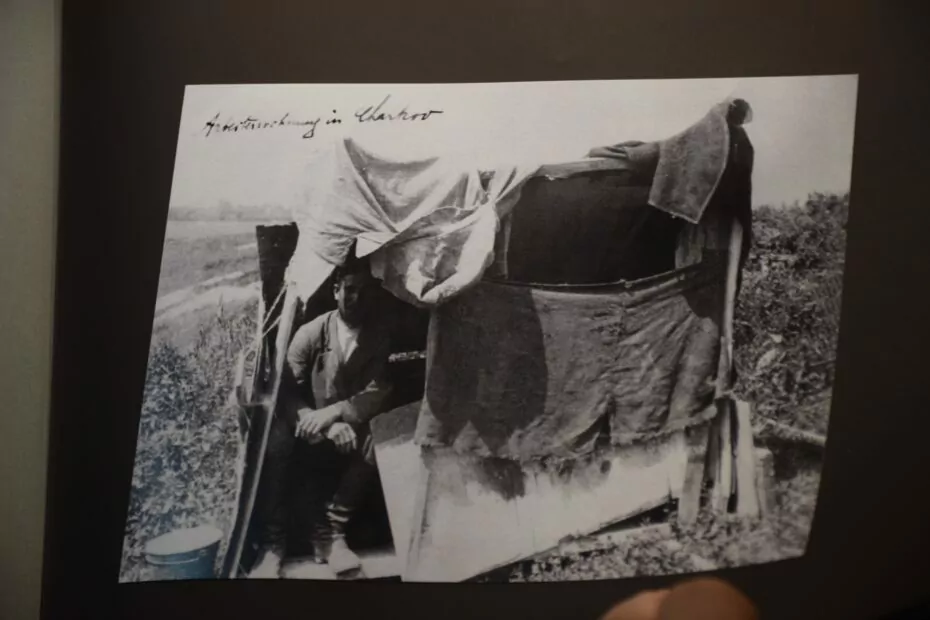

Soviet authorities were destroying evidence of the Holodomor in Kharkiv, but Austrian engineer Alexander Wienerberger was able to save stunning photographic evidence of the famine in the capital of Soviet Ukraine.

The engineer’s great-granddaughter, Samara Pierce, provided an album of photos Wienerberger took during the Holodomor.

From 1932 to 1933, Wienerberger worked at the Kharkiv “Plastmas” plant. He was appointed head of the modernization of the factory that was abandoned at that time. Ukrainian lands struck the engineer with a contrast: once a country rich in food, fertile fields, and meadows with livestock turned into a land of exhausted, hungry, and haggard people.

From March 1933, Soviet newspapers terrorized villagers who did not want to join collective farms and threatened them with terrible punishments. At the beginning of April, the Soviet authorities promised to return relatives exiled to Siberia to those villagers who gave up their fields. People began to cultivate the fields and started using their grain reserves. After that, employees of the SPA (State Political Administration – a secret Soviet special service, the predecessor of the NKVD, The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) confiscated the last food from the hungry villagers.

Fearing hungry villagers would go to the cities, the authorities banned the open sale of railway tickets for six months. It was also forbidden to send food by train or mail across the country so that people in the cities could not help their relatives in the villages.

The Holodomor did not touch Alexander and his family personally

It is hard to imagine that an engineer with foreign citizenship, whom Moscow sent to Kharkiv with an important mission, could face hunger in any way.

But this tragedy – the slow and painful extinction of an entire nation – could not go unnoticed.

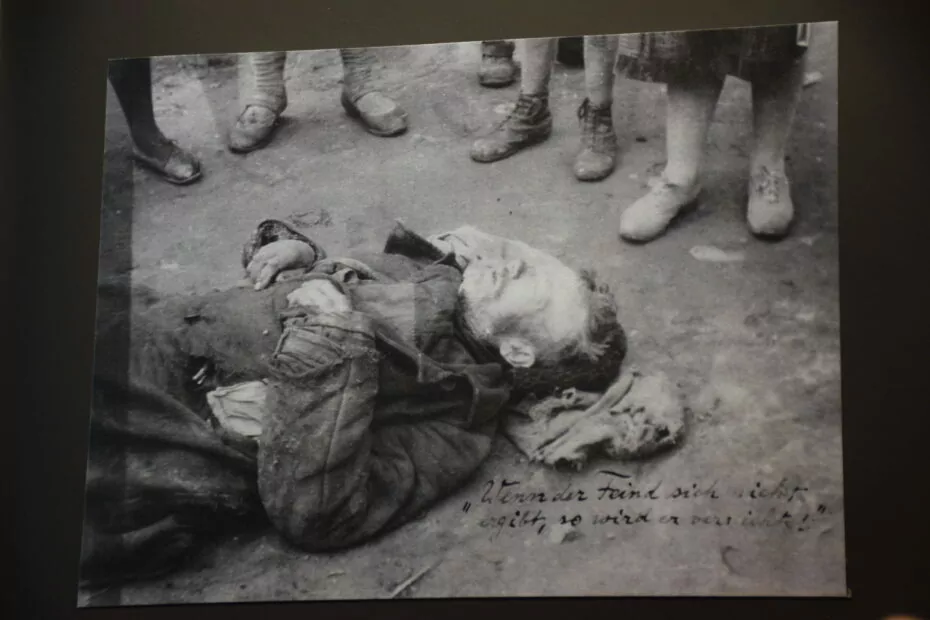

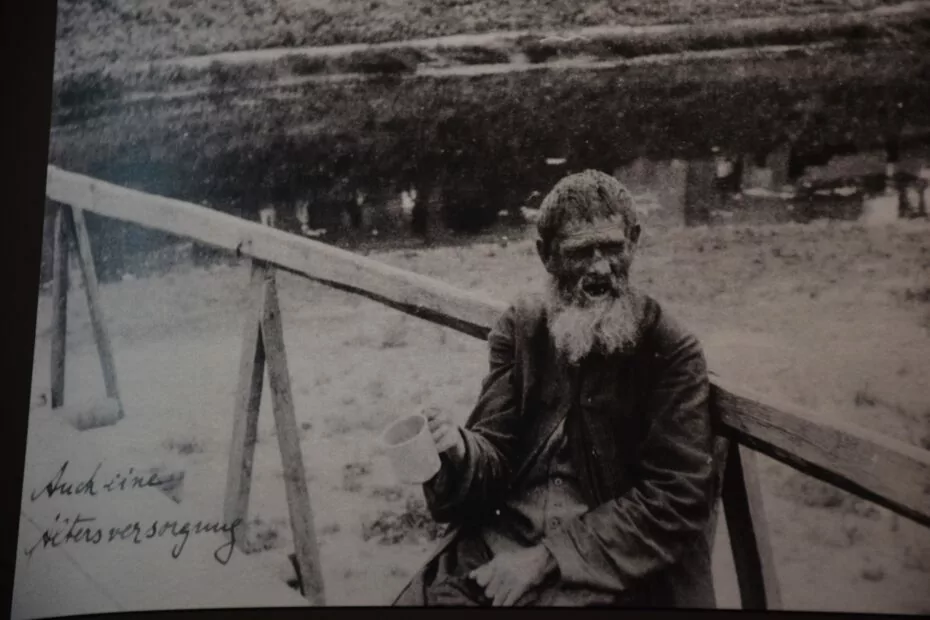

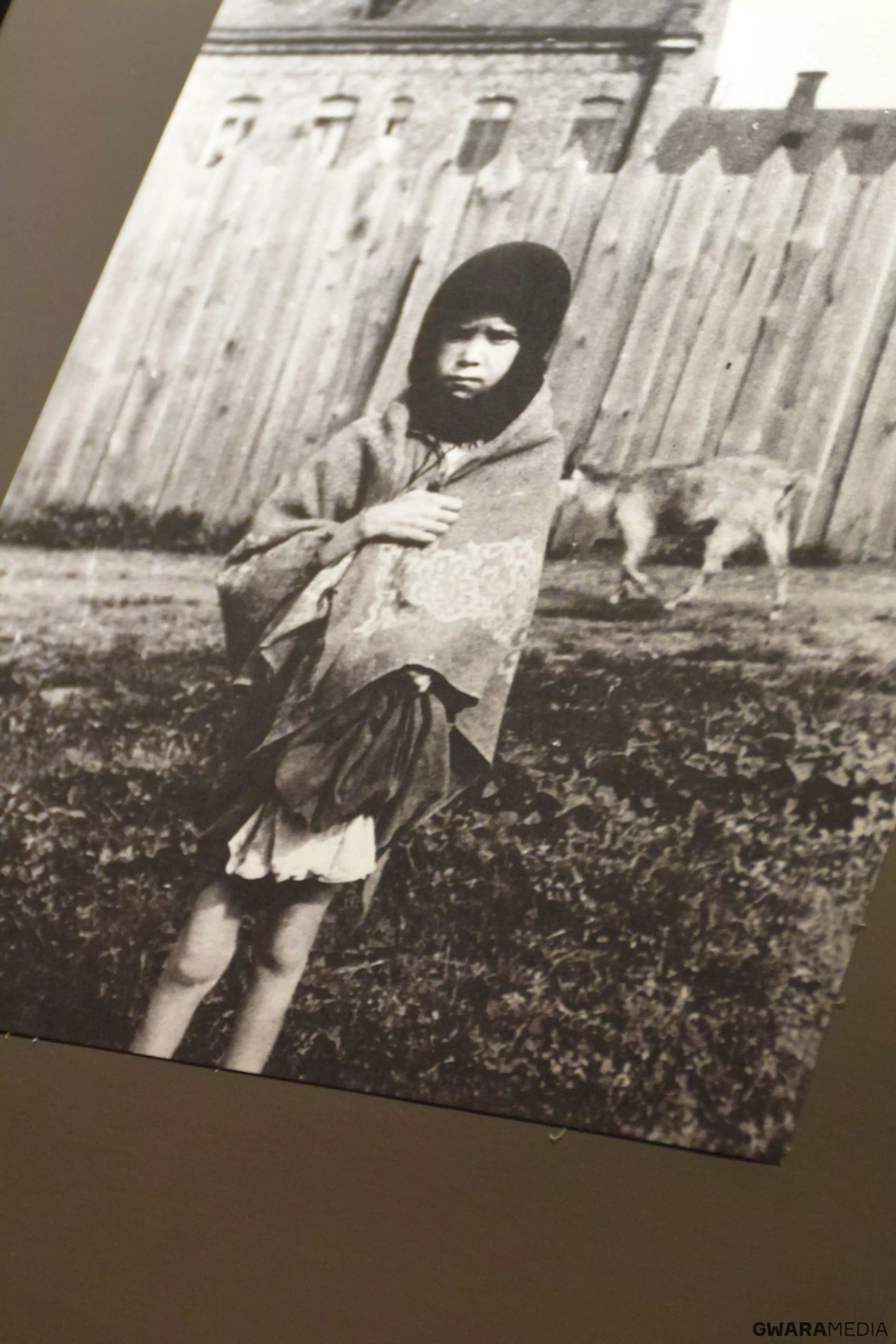

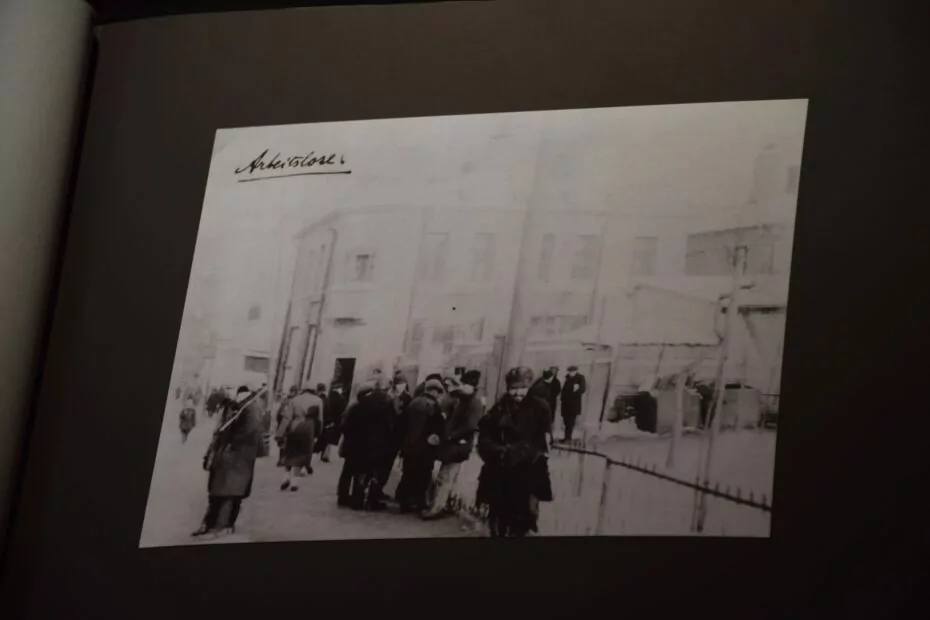

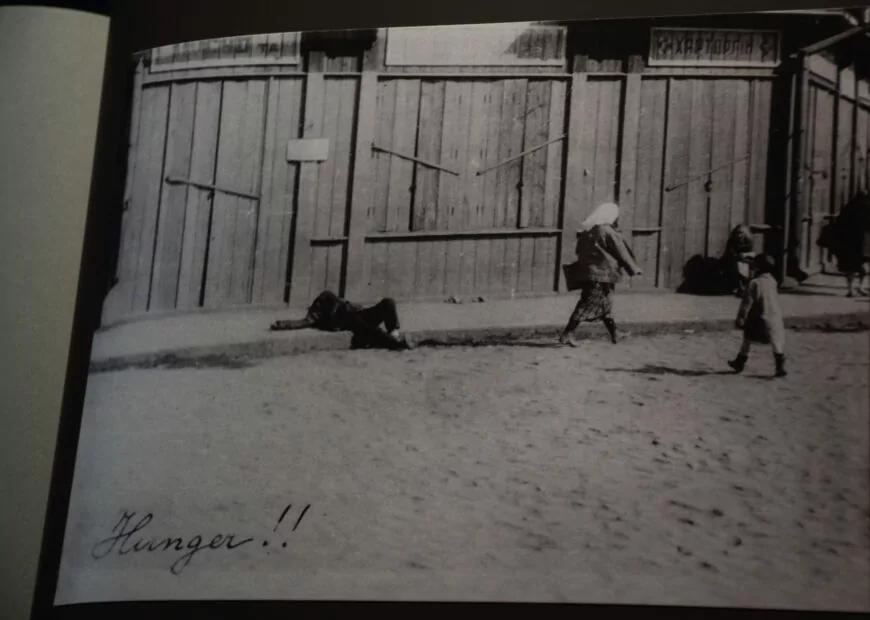

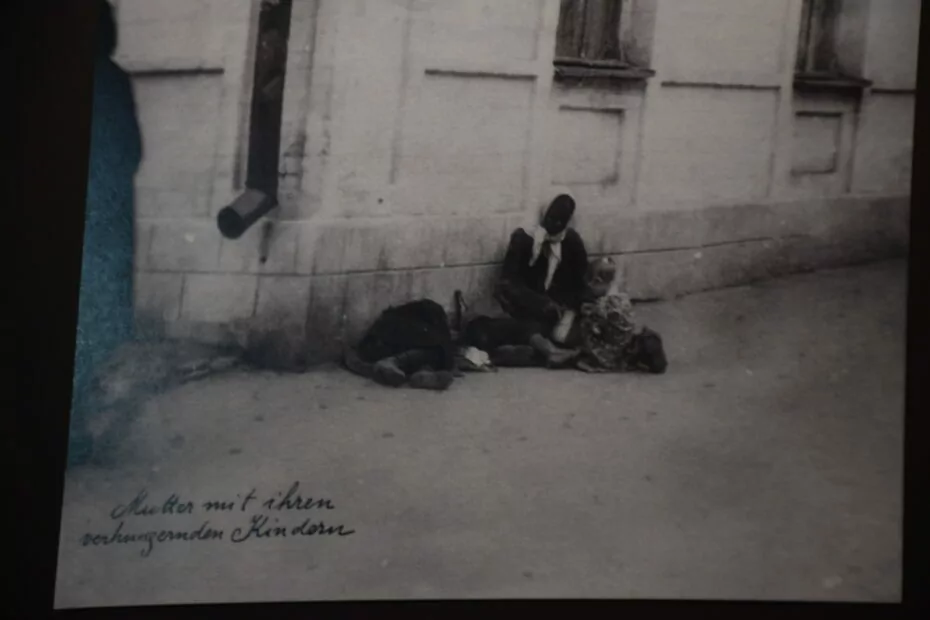

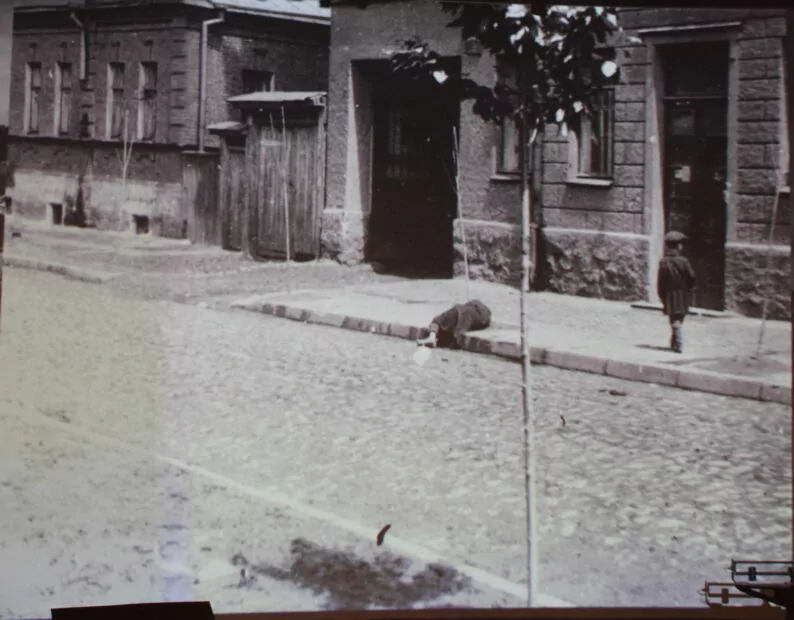

Throughout the spring and summer of 1932-1933, Wienerberger documented the episodes and consequences of the genocide of the Ukrainian people. He managed to secretly take about 100 photographs, recording Kharkiv and its surroundings during the Holodomor.

The pictures show the bodies of half-alive or dead Ukrainians lying just on the streets of Kharkiv, numerous lines for food, empty shop windows, workers’ dugouts, and mass burials of people starved to death.

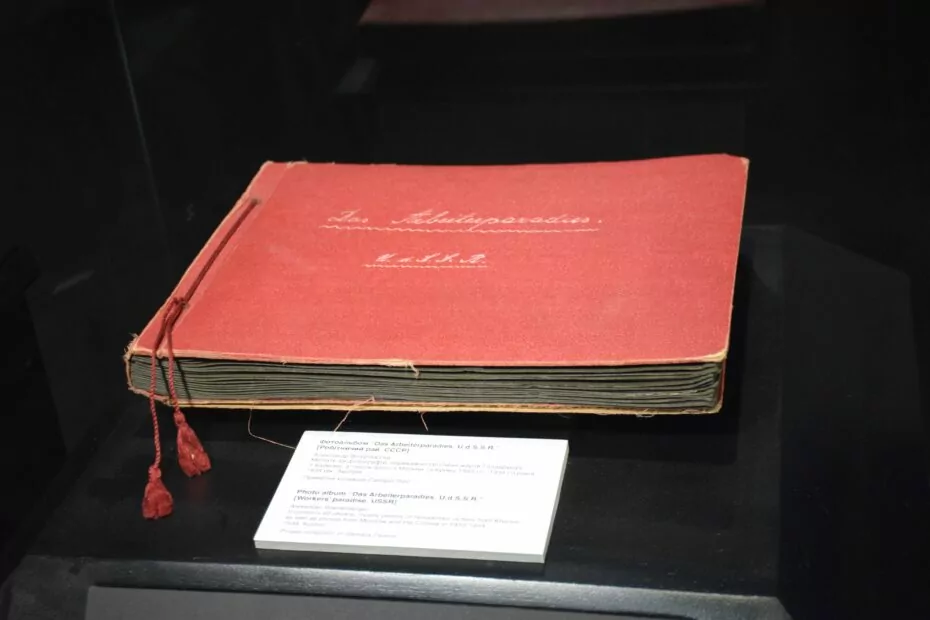

Photo Album Das Arbeiterparadies. U.d.S.S.R. (also known as the Red Album, or Workers’ Paradise. USSR)

The album was composed by Alexander Wienerberger after returning to his homeland, Austria, in 1934 from the pictures he took on the territory of the USSR. The decision to finally leave the Soviet Union was also made under the influence of the Holodomor in Ukraine.

Crimea and Moscow are also recorded in the album, but most photos were taken in Kharkiv in 1933, particularly near Kholodna Hora. The factory, which Alexander managed, was located there.

All the photos included in the album were taken in secret. In the USSR, it was forbidden to record anything that could discredit the image of the state, and even more so on the world stage.

Every photo of Soviet life “as it is” meant taking the risk of being suspected of espionage and anti-Soviet activities by its author. Shortly before departure, Wienerberger sent his pictures to Austria by diplomatic mail, which did not allow searches of shipments by the authorized bodies of the USSR.

In 1935, Ewald Ammende’s book Muss Russland Hungern? [“Should Russia starve?”] was published, with Wienerberger’s pictures of Holodomor, but without crediting him as the photographer for security reasons. And in 1939, Alexander’s diary was published. It’s called Hart auf hart, 15 Jahre Ingenieur in Sowjetrußland [“Fateful times. 15 years as an engineer in the Soviet Union”]. The book has two separate chapters describing the Holodomor’s events and 52 photographs from the USSR.

“I rode the Moscow-Kharkiv train to my new job, and at every station, I saw a huge number of wagons with villagers and their families, who were sent under guard “far north to white death.”

The fields were left uncultivated, and the unharvested grain rotted under the autumn rains. Even in 1926, these lands were just as prosperous after the world and civil wars. How inhuman this force must be to turn a prosperous country that was luxuriant in food into a ruin,” reports Wienerberger.

The name of Wienerberger himself and his visual legacy

In 1984, the priest of the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Vienna, Oleksandr Osthaim-Dzerovych, found the album with the engineer’s notes in the Vienna Diocese library. The following year, Canadian researcher Marko Tsarynnyk found information about Wienerberger in the documents of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Great Britain.

In 2003, a group of researchers led by historian Vasyl Marochka published the already attributed photos of Wienerberger in the monumental work “Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine: Causes and Consequences”, re-updating the history and value of Alexander’s photographs of Kharkiv.

In 2012, Samara Pearce, Wienerberger’s great-granddaughter, visited Kharkiv to record locations from Alexander’s photographs and later, combining her photographs with those of 1933, created her own photo project, “Masks of the Holodomor.”

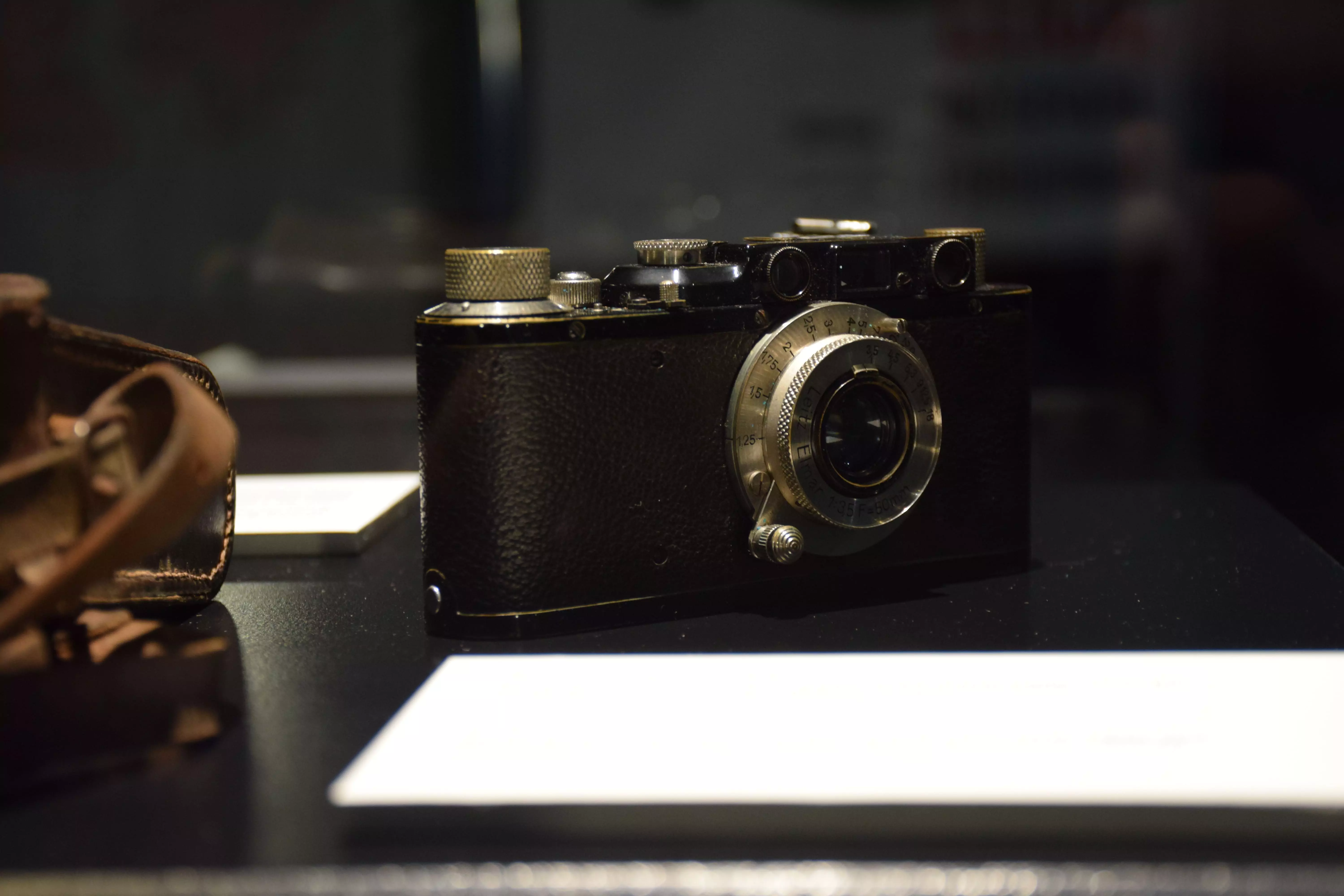

And in 2015, she found the same Leica II camera and the same “Red Album” in her relatives’ belongings, which was exhibited in Ukraine for the first time in 2022.

For decades, it wasn’t allowed to talk about the Holodomor in Soviet Ukraine. Currently, in Ukraine, the Holodomor of 1932-1933 is regarded as an act of genocide of the Ukrainian people, carried out by the USSR government through the organization of an artificial mass famine, which led to millions of death in the countryside on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR.

Text by Denys Glushko

Translated by Anastasia Kizyma

Edited by Tetiana Fram